Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence

With Maria Popova: The Marginalian

In these darkening times, when the powerful and the political class have become utterly corrupted, and indifferent to the concerns of ordinary people, there are, as a kind of counterwave, a significant number of people trying to trigger a new Enlightenment. Maria Popova is one of the best and the brightest.

A Sense of Place Magazine is an unabashed fan of Maria Popova’s celebrated blog The Marginalian, easily one of the best literary journals in the world.

Her book Figuring is a fascinating study of the loneliness of genius before the internet age.

https://asenseofplacemagazine.com/a-celebration-of-genius-maria-popova-and-figuring/embed/#?secret=xGfU2xkmTw#?secret=36ZfJVgmFj

Maria Popova is a Bulgarian born New York based polymath who has it sometimes seems read everything so the rest of us don’t have to. Not just supremely intelligent, she has an uncanny eye for beauty combined with a deeply felt sense of what makes us human.

“Intelligence supposes good will,” Simone de Beauvoir wrote. “Sensitivity is nothing else but the presence which is attentive to the world and to itself.” Yet our efforts to define and measure intelligence have been pocked with insensitivity to nuance, to diversity, to the myriad possible ways of paying attention to the world. Within the human realm, there is the dark cultural history of IQ. Beyond the human realm, there is the growing abashed understanding that other forms of intelligence exist, capable of comprehending and navigating the world in ways wildly different from ours, no less successful and no less poetic. One measure of our own intelligence may be the degree of our openness to these other ways of being — the breadth of mind and generosity of spirit with which we recognize and regard otherness.

The science-reverent English artist James Bridle invites such a broadening of mind in Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence (public library). He writes:

The tree of evolution bears many fruits and many flowers, and intelligence, rather than being found only in the highest branches, has in fact flowered everywhere.

[…]

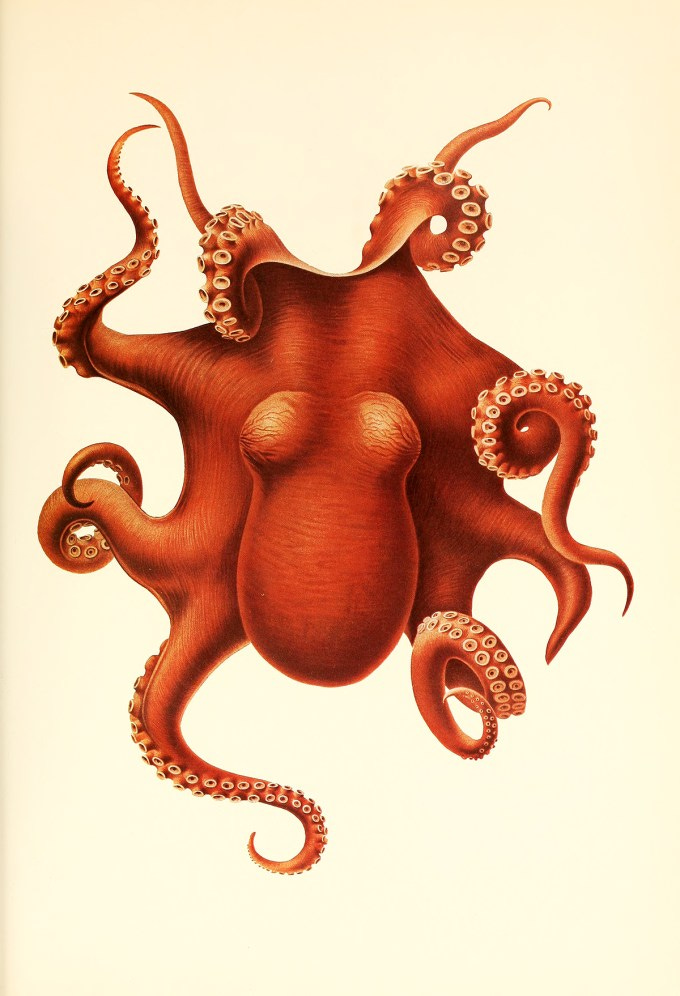

There are many ways of “doing” intelligence: behaviourally, neurologically, physiologically and socially… Intelligence is not something which exists, but something one does; it is active, interpersonal and generative, and it manifests when we think and act. We have already learned — from the gibbons, gorillas and macaques — that intelligence is relational: it matters how and where you do it, what form your body gives it, and with whom it connects. Intelligence is not something which exists just in the head — literally, in the case of the octopus, who does intelligence with its whole body. Intelligence is one among many ways of being in the world: it is an interface to it; it makes the world manifest.

Borrowing ecological philosopher David Abram’s notion of “the more-than-human world,” he adds:

Intelligence, then, is not something to be tested, but something to be recognized, in all the multiple forms that it takes. The task is to figure out how to become aware of it, to associate with it, to make it manifest. This process is itself one of entanglement, of opening ourselves to forms of communication and interaction with the totality of the more-than-human world, much deeper and more extensive than those which can be performed in the artificial constraints of the laboratory. It involves changing ourselves, and our own attitudes and behaviours, rather than altering the conditions of our non-human communicants.

[…]

To think of intelligence in this way is not to reduce its definition, but to enlarge it. Anthropocentric science has argued for centuries that redefining intelligence in this way is to make it meaningless, but this is not the case. To define intelligence simply as what humans do is the narrowest way we could possibly think about it — and it is ultimately to narrow ourselves, and lessen its possible meaning. Rather, by expanding our definition of intelligence, and the chorus of minds which manifest it, we might allow our own intelligence to flower into new forms and new emergent ways of being and relating. The admittance of general, universal, active intelligence is a necessary part of our vital re-entanglement with the more-than-human world.

A century and a half after the Victorian visionary Samuel Butler presaged the emergence of a new branch on the tree of life — a “mechanical kingdom” of our own making, comprising our machines governed by a “self-regulating, self-acting power which will be to them what intellect has been to the human race” — Bridle offers an optimistic implication of this redefinition for the future of what we now call “artificial intelligence”:

If intelligence, rather than being an innate, restrictive set of behaviours, is in fact something which arises from interrelationships, from thinking and working together, there need be nothing artificial about it all. If all intelligence is ecological — that is, entangled, relational, and of the world — then artificial intelligence provides a very real way for us to come to terms with all the other intelligences which populate and manifest through the planet.

What if, instead of being the thing that separates us from the world and ultimately supplants us, artificial intelligence is another flowering, wholly its own invention, but one which, shepherded by us, leads us to a greater accommodation with the world? Rather than being a tool to further exploit the planet and one another, artificial intelligence is an opening to other minds, a chance to fully recognize a truth that has been hidden from us for so long. Everything is intelligent, and therefore — along with many other reasons — is worthy of our care and conscious attention.

Complement with Walt Whitman on the wisdom of trees, Ursula K. Le Guin on the poetry of penguins, and Marilyn Nelson’s spare, splendid poem about octopus intelligence, then revisit Nick Cave on music, feeling, and transcendence in the age of AI.

To follow The Marginalian, which we couldn’t recommend more highly, go here.