Transhumanism is an idea Centuries in the Making

TOTT NEWS.

Eugenics and transhumanism go hand-in-hand, and modern ideas about ‘transcending the human’ can actually be traced back to works that were written centuries ago.

Transhumanism is the belief that, in the future, science and technology will enable us to transcend our bodily confines. Scientific advances will transform humans and, in the process, eliminate ageing, disease, unnecessary suffering, and ultimately our earthbound status.

Artistic representations of humans uploading their minds to cybernetic devices or existing independently of their bodies abound are seen pictured through the Freudian propaganda networks.

In Altered Carbon (2018-2020), for example, we are introduced to a future where human consciousness can be downloaded onto devices called “cortical stacks”.

This technology reduces physical bodies to temporary vehicles or “sleeves” for these storage devices which are implanted and swapped between various bodies:

https://youtu.be/M8PsZki6NGU

Science fiction has long been used as a collective subconscious messaging tool for future manifestation.

The Matrix (1999, 2003), which has become a staple movie of the awake community, depicts humans living in a digital simulation while their bodies remain inactive in liquid-filled pods.

RELATED:

Transhumanism: When science

fiction becomes reality

There are many more examples that explore our transhuman future in monstrous creations — examining the boundaries between human and machine.

But these speculations are not limited to art and science fiction.

The public intellectual Sam Harris and world-renowned physicist David Deutsch imagine a future where we are able to download conscious states and live in matrix-like virtual simulations.

The historian Yuval Noah Harari suggests, in the not too distant future, these technological advancements will transform us into new godlike immortal species.

Some thinkers, like the philosopher Nick Bostrom, believe we might already be living in a computer simulation. Elon Musk is developing brain-machine interfaces to connect humans to computers.

These imaginings of our transhumanist future take many divergent forms, but they share the idea science will enable us to ‘free our minds from bodily constraints’.

But these ideas aren’t modern.

In fact, the desire to transcend our nature is a continuation of the Enlightenment ideal of ‘human perfectibility’.

Today’s ideas of transhumanism can be directly traced back to two 18th century thinkers.

MARQUIS DE CONDORCET

Life will have ‘no assignable limit’

Marquis de Condorcet (1743-1794) was a French revolutionary who wrote and spoke extensively on the notion that the new scientific age of ‘enlightenment’ would bring about unprecedented progress.

He has been called “the last witness” of the Age of Enlightenment; a period of history that has been written to depict a wonderful ‘progression’ of the world — but was really an upheaval that laid the foundation for the birth the eugenics movement.

From the occult whispers of the mid-18th Century, to the Revolution of Scientism in the late-19th Century — a two and a half century vision has been in motion to transform the human species.

Condorcet was a key part of this early shift.

He was a mathematician who aimed to apply a ‘scientific model’ to the social and political dimensions of society, and thought improvement in education would ‘produce more knowledge’ — creating an ever upward ‘spiral of progress’.

RELATED:

Schooling was designed

to indoctrinate society

His reception speech to the French Academy in 1782 captured the optimistic spirit of the age.

He declared: “the human mind will seem to grow and its limits to recede” with the advancement of science.

Condorcet imagined an era in which science would lead to humans ‘transcending’ their bodies and, in the process, attaining immortality.

In Outlines of an Historical View (1795), he wrote:

“Would it even be absurd to suppose […] a period must one day arrive when death will be nothing more than the effect either of extraordinary accidents, or of the flow and gradual decay of the vital powers; and that the duration of the middle space, of the interval between the birth of man and this decay, will itself have no assignable limit?”

Condorcet speculated about utopian possibilities and wrote a piece on the “perfectibility of society”.

He gave no concrete definition of a “perfect” human existence, but he believed that the progression of the human race would inevitably continue throughout the course of its existence.

His thoughts prompted Thomas Malthus to write his famous paper on unsustainable population growth.

The Malthusian Trap, as it is called, was the direct inspiration for Bill Gates and his modern population control agenda.

It is all an extension of the same ideas, the same vision.

Condorcet was not alone in his promotion of these radical ideas.

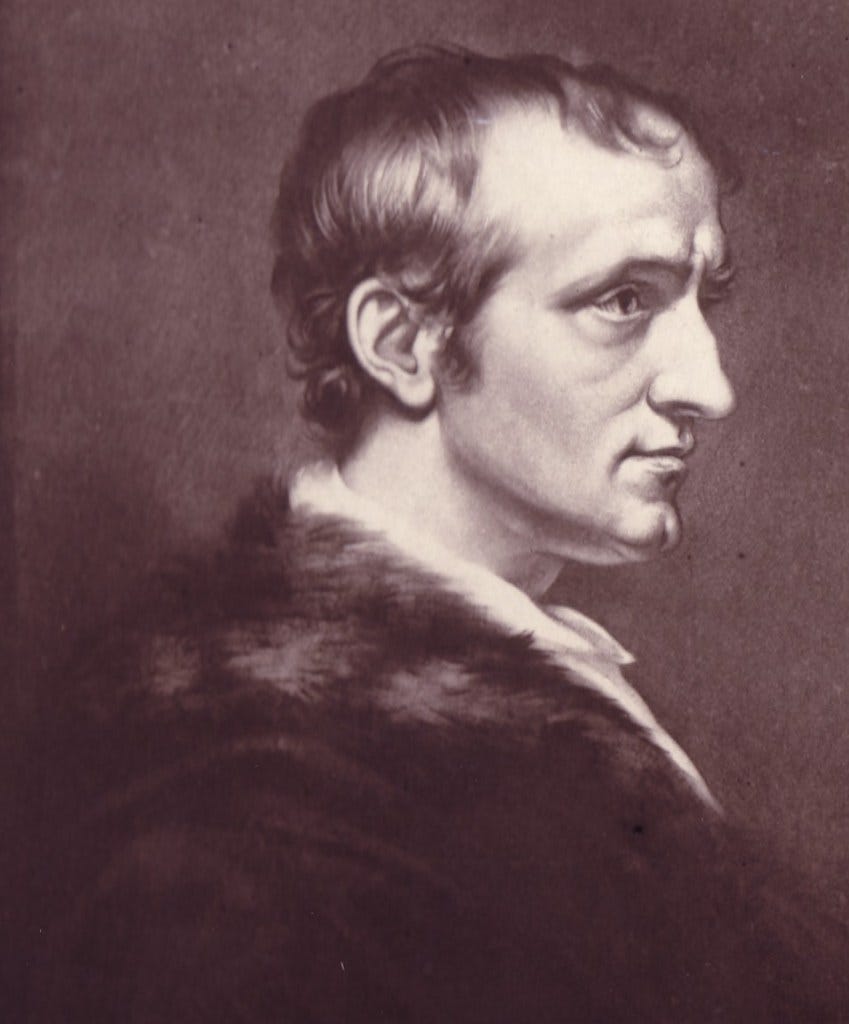

WILLIAM GODWIN

The ‘extinction of anguish and passion’

Enlightenment thinker William Godwin (1756-1836) was convinced science would lead to ‘human perfectibility’ and was a major advocate of a new wave of posthuman thinking.

Godwin was a political radical whose sympathies lay with contemporary French revolutionaries like Condorcet and he believed an ‘expansion in knowledge’ would lead to improvements in our understanding, and thereby ‘increase our control over matter’.

Godwin outlined this vision in his book, Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness (1793).

In this book, he wrote that human passions and desires would become extinct, along with disease, anguish, melancholy and resentment.

This was a future in which people no longer had sex, nor reproduced.

The Earth instead would be populated by disembodied humans who have achieved immortality.

In the 1700s, this would have seemed like the most insane thing you had ever heard.

Yet, roughly a century and a half before Aldous Huxley would detail the blueprint of this vision in his dystopian novel Brave New World, Godwin has already envisioned a future like this.

Godwin had acknowledged that an increase in the standard of living (as he envisioned) could cause population pressures, but he saw an obvious solution to avoiding distress:

“Project a change in the structure of human action, if not of human nature. Specifically, the eclipsing of the desire for sex by the development of intellectual pleasures.”

The ‘intellectual pleasures’ would become the soulless materialistic consumer empires to numb their brains.

Godwin’s daughter, Mary Shelley, went on to write one of the earliest literary works to depict transhumanism, Frankenstein in 1818.

What are the odds of that?

Her vision of a scientific future was much less rosy.

For early transhumanists, ‘human perfectibility’ was unlimited and, more importantly, achievable.

All it took was the alteration of the species — a notion that would be accepted one hundred years later with the rise of the Theory of Evolution. Carried out by Aldous’ grandfather, Thomas. ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’.

SCIENCE FICTION.. OR SCIENCE FUTURE?

Godwin and Condorcet imagined humans progressing towards perfect harmony, transcending bodily existence and achieving immortality without desires nor suffering.

This is the exact same utopian dribble that modern transhumanists like Elon Musk say on a daily basis.

‘No more pain, no more suffering, no more human limitations’.

Now, as the rise of the Fourth Industrial Revolution sweeps the world, the masses believe this notion more than ever after 250 years of collective programming — and wait to willingly accept it.

Google has a $1.5 billion research centre to ‘solve death’, Facebook looks to create an alternate reality with the Metaverse, microchips are promoted as the future ‘solution’ to all ailments and much more.

Will we become the immortal human-machine gods, as Yuval Noah Harari predicts?

Or will we still be waiting to transcend our fleshy bodies in the 23rd century?

Only time will tell.

The transhumanists are determined to make this a reality in decades.

But here is the catch: Unless you are in the ‘big club’, you are likely to be a victim of this shift, not a beneficiary.

The head of Microsoft recently said that AI could transform the world into 1984 by 2024.

Unless anyone is there to stop them, our species may never be the same again.

They have had quite the head start on all of us.