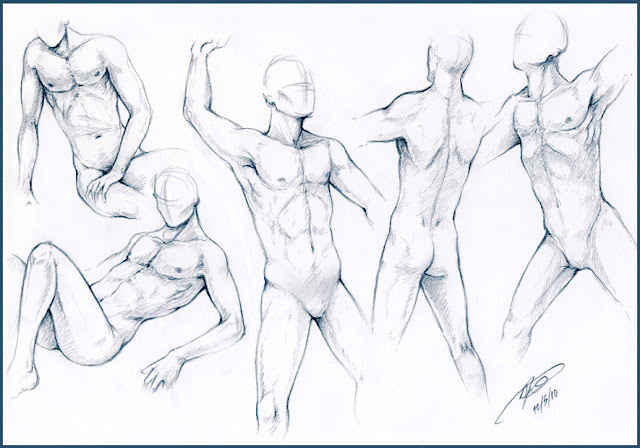

Sketches Moving Men by Rosaka Chan

His friend was dying of AIDS.

That much was obvious.

He had run into Paul, who he hadn't seen for several years, at St Vincent's Hospital, which he was attending for another matter unrelated to AIDS.

But he was amazed at the number of people he encountered who he had known from the past, each attending their various treatments for the disease which had ravished so many of his contemporaries and brought them, diminished from their illnesses, to these broad steps and its large, muffled foyer.

Each of them was a long way from the individuals he had first met. Back then, in the 1980s, they had been full of life and flirtations, lovers and intrigue.

Now they were simply sick. Aging and dying in a way none of them had planned or wish; a feeble outcome from the dynamic people they once had been.

And thus it was he met Paul, again.

Paul had been an artist, back then, always sketching the people he knew, the young men who had frequented his various apartments, almost as if in secret. Whatever went on behind those doors was not for everyone to know.

All these years later, away from the intriguing paradises of inner Sydney, Paul was living with his long term lover in a Randwick apartment above a Thai restaurant, which he had helped set up his lover in.

Downstairs was all the bustle of a popular Thai restaurant, of which Sydney was increasingly full.

Customers sometimes queued out the door. It was always busy.

Following the instructions Paul had given him on the steps of the hospital, he had dropped by one day when he was driving past; having completed another mission from the Goddess.

It was night time and he was a little lost; wanting to ignite the flames of old. The warmth, the camaraderie, all the people they had known together.

Downstairs the boyfriend, now restaurant manager, pointed him to the stairs which led to the apartment upstairs; and then accompanied him to the door.

Paul was frail, and could not sustain the pressure of unwanted guests. Like so many, Paul had become increasingly isolated as his illness progressed. He didn't want people to see him the way he was now. He wanted people to remember him the way he used to be.

The boyfriend seemed relieved when Paul greeted him warmly and allowed him into the inner sanctum of his apartment, a humble place littered with memories, ghosts, suffering.

Paul was smoking a lot of marijuana to offset the nausea of the AIDS treatments that he was enduring; the prolonging of life for life's purpose, for a reason nobody quite new, perhaps in the forlorn hope that a cure was just around the corner.

For so many years nobody had known what the peculiar American illness now decimating the ranks of Sydney's gay population actually was.

The fear campaigns initially adopted by the Australian government, the grim reaper advertisements which while doing little to stop the spread of the disease had done much to instill fear of gay people in the general population, had now given way to more progressive and targeted campaigns.

But even so; AIDS held a stigma of the lost and the marginalised. It was the ultimate price to pay for once having been at the forefront of social change and sexual experimentation, for the wild parties, the Mardi Gras, the legal and political campaigns which had found sympathetic ears at the highest level of government.

And so they settled down to talk and reminisce, in that apartment above the bustle of the restaurant, the aura of long term love, the delicacy of discretion and illness, the concern of his healthy Thai boyfriend.

Paul told him all the stories about how he had spent years in India; as a gay man the object of great curiosity and attention from the local Indian men, who used to virtually queue at the door of his house, their own women, mistresses of their own domain, well under wraps.

And rolled joint after joint as the evenings settled into nights; and the throbbing tumult of the bars and clubs only a few suburbs away distant now in time and space; an unfocused longing from a different past.

A time they thought would never end.

Or at least end in a more glorious place than this.

Paul had destroyed almost all the paintings and drawings he had so painstakingly done all those years ago.

He couldn't understand why; and Paul tried to explain. He wanted to be rid of everything, all that had been, all that had made him sick, that had betrayed him so totally.

He showed him the fragments of sketches that he had kept; including pictures of himself and his then lover Martin, and he was particularly taken by the fine lines of Martin's then feline form.

And each drawing, or scrap of a drawing, spoke of the obsessions with men he had known and loved. There wasn't any laughter to be had in the rediscoveries.

He didn't hear of Paul's death immediately, the old social networks having been so thoroughly destroyed by the wasting disease, and therefore didn't attend the funeral.

He didn't try to talk to the restaurant manager boyfriend after he learnt of Paul's death.

He just continued to drive past the restaurant and think of him each time he passed.

He assumed the boyfriend would eventually sell up the restaurant at a considerable profit and return to his homeland.

And the memory of Paul continue to drift into nothingness, as he had wished. Just as he had destroyed his own sketches and paintings; in themselves a record of a bygone era. The suffering wiped clean. Only the memory of his laughing, devious, talented face and long intimate evenings lingering in the minds of some until they, too, were gone.