The World's First Fake News: The Cello and the Nightingales

Maria Popova: The Marginalian.

In these darkening times, when the powerful and the political class have become utterly corrupted and indifferent to the concerns of ordinary people, there are, as a kind of counterwave, a significant number of people trying to trigger a new Enlightenment. Maria Popova is one of the best and the brightest.

A Sense of Place Magazine is an unabashed fan of Maria Popova’s celebrated blog Brain Pickings, which has now evolved into The Marginalian, easily one of the best and most accessible literary journals in the world.

Her book Figuring is a fascinating study of the loneliness of genius before the internet age.

https://asenseofplacemagazine.com/a-celebration-of-genius-maria-popova-and-figuring/embed/#?secret=xGfU2xkmTw#?secret=36ZfJVgmFj

Maria Popova is a Bulgarian born New York based polymath who has it seems read everything so the rest of us don’t have to. Not just supremely intelligent, she has an uncanny eye for beauty combined with a deeply felt sense of what makes us human.

Here is an extract from her recent essay The Cello and the Nightingales: How the World’s First Fake News United Humanity in Our First Collective Experience of Empathy for Nature. You can read the piece in full by following the link to The Marginalian at the bottom of this piece.

In the high summer of 1977, 100 years after Thomas Edison devised the first technology for recording and reproducing sound, the Voyager reached the poetic gesture of its Golden Record into the cosmos, carrying the universal language of our species — a Navajo night chant and a Bach fugue, a millennia-old Chinese song and a Beethoven string quartet, Senegalese percussion and a shepherd’s song from my native Bulgaria — encoded with the hope that some other life-form in some other corner of the universe might have the consciousness to hear it and fathom who we are.

Half a century earlier, a young cellist in a forest achieved what the Golden Record is yet to achieve, making contact with another consciousness through music — right here on Earth, in this wilderness of wonder already rife with alien minds.

In the process, Beatrice Harrison (December 9, 1892–March 10, 1965) linked human consciousnesses around the world into a kind of planetary übermind vibrating with an unprecedented collective experience — an experience rooted in our relationship to nature, which is also our relationship to each other. In the haunting interlude between two World Wars — decades before the Moon landing, years before the birth of television, a quarter century before Alan Turing pioneered digital music — a voice wild and free spilled its liquid rapture from the waves of a young medium, slaking the ancient thirst for harmony in the human soul, singing the history of the future.

With the era of collective grief and collective joy still behind the horizon of technologies unimagined by their makers, here was the world’s first nature broadcast, transmitting the sound of a wild creature in its habitat — the creature serenaded by Keats in one of his most beloved poems — into the indoor habitats of humans the world over, who heard the song of Milton’s “Sweet Bird that shunn’st the noise of folly, most musicall, most melancholy” for the very first time. Here was the first interspecies creative collaboration (not counting evolution itself).

Very possibly, it was also the world’s first planet-wide fake news. Most certainly, its authenticity matters not one bit to what it accomplished, which might just be our best blueprint for a more possible future.

What happened between the cello, the nightingale, and the world that spring night in 1924 was the improbable dream of a woman not ahead of her time but beyond it. A visionary furnishing the proof of a medium through the poetry of its message, finding what is most beautiful in human nature through its harmonic resonance with the rest of nature. A musician making not just music but meaning — the meaning of connection and kinship, of enchantment and empathy. She had managed to persuade the bosses of the newborn BBC to take a grudging risk on her dream — a risk the bosses of the centenarian BBC would confess ninety-eight springs later very possibly ended in failure broadcast as symphonic success.

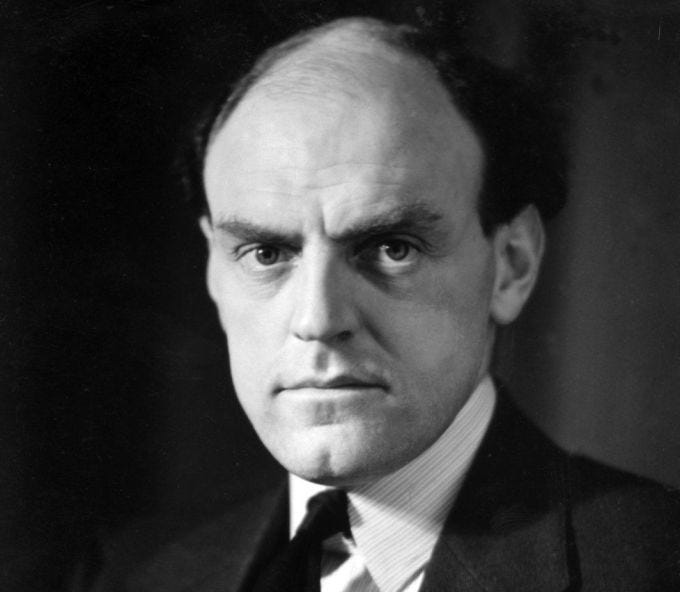

BBC director John Reith, 1st Baron Reith

This was the dawn of mass media, the incubus of social media, the beginning of the end of truth, when the cathedral of commerce began bending humanity to its knees the corporations that made a business of culture first began choosing what is profitable over what is right. The men in charge, these knighted men of power and insecurity, had invested too much to fail in public. A Plan B was hatched in preparation to fake success if need be: As the broadcast experiment neared, nervous that all the commotion of cables and microphones would frighten the birds, they hired (it is claimed nearly a century later) an understudy — the professional whistler and bird imitator Maude Gould, who performed in variety shows as Madame Saberon.

The morning of May 19, 1924, Beatrice Harrison watched “all the paraphernalia of the BBC” spill into her garden. About a hundred yards from where the nightingale sang with her each solitary night, they set up a sensitive microphone and hooked it up to an amplifier. Headphone cables and telephone landlines criss-crossed the sea of bluebells.

The BBC producers setting up a broadcast in Beatrice’s garden

When nightfall came, Beatrice crept up with her cello, crooking her chair halfway into the most opportune ditch, knowing that “the exquisite voice was there, under a thicket of oak leaves, ready to sing to his little wife.” She proceeded to play for two hours, hearing all kinds of curious noises — insects buzzing, rabbits nibbling on the wires, her donkey whinnying at the chaos of strangers — but the nightingale was nowhere in the symphony of night.

And then, suddenly, an hour before midnight, the world heard the exquisite voice singing to the cello. For nearly a century, it would be taken for the voice of the nightingale. But in 2022, the BBC would reveal that the impatient producers may have summoned Madame Saberon to sing the part.

This was a live broadcast and there is no surviving recording to be analyzed. All that is known is that Madame Saberon may have been hired, that she was an excellent bird imitator — an artistic triumph in its own right — and that on the other side of thousands of radio receivers, the world fell in love with the nightingale.

If the large mammal did impersonate the part of the tiny feathered dinosaur, she was so impeccable that even Beatrice, who had been listening to the real bird night after night, didn’t seem to realize it. This is what she recounts happened when the song unspooled into the night:

[The nightingale’s] voice seemed to come from the Heavens… I shall never forget his voice that night, or his trills, nor the way he followed the cello so blissfully. It was a miracle to have caught his song and to know that it was going, with the cello, to the ends of the earth.

To read the full story go here:

https://www.themarginalian.org/2022/06/05/the-cello-and-the-nightingales-beatrice-harrison/