The Rise of Brain Reading Technology

By TOTT News

Technologies allowing thoughts and feelings to be translated and shared into digital form are already a reality, and in the era of neurocapitalism, your brain will soon require its own rights.

In the modern world, brain-computer interfaces (BCI) allow us to connect our minds to computers for medical purposes, and now big tech is seeking to transform this into consumer commonplace.

“Nothing was your own except the few cubic centimeters inside your skull,” says Winston, the protagonist from George Orwell’s dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, published in 1949.

The comment is meant to highlight the repressive surveillance state the characters live in. In retrospect, however, it may show just how lucky they are: At least their brains are still private.

There is a lot is going on in the rapidly emerging field of brain-computer interface (BCI) design. Corporations and governments have recently been making aggressive investments in technology explicitly created to allow your mind to control and interact with connected devices.

The vision of this tech will result in ongoing, real-time connections to your innermost thoughts. Gone is the need to use vocals to gain Alexa’s attention; rather, you will simply have to think.

A BCI is a device that allows for direct communication between the brain and a machine, with the foundation to this technology being the ability to decode neural signals that arise and translate them into commands that can be recognised by the machine.

The data they can gather is currently based around measuring the physical movements people make or their emotional state. But, as machine-learning algorithms become more sophisticated and BCI hardware becomes more capable, it will become possible to read thoughts with greater precision.

Today, there currently exists two approaches that allow a user to connect the human brain to external computing systems, defined as “invasive” and “non-invasive” techniques:

Non-invasive systems read neural signals through the scalp, typically using EEG, which are the same technologies used by neurologists to interpret the brain’s electrical impulses.

Invasive systems, meanwhile, involve direct contact between the brain and electrodes. They are being used experimentally to help people that have experienced paralysis to operate prostheses, such as robotic limbs or to aid people with hearing or sight problems to recover senses they’ve lost.

As well as software improvements, additional advancements are beginning to be used by BCI systems. These include focused ultrasound and transcranial direct-current stimulation.

Most of these systems had previously been restricted primarily to the fields of science and medicine, however, in an age of increasing technological developments, companies are now beginning to research how they can capitalise on these techniques in a growing consumer world.

Furthermore, governments are now also beginning to adopt the technology in various programs.

The world of big tech is expanding, as reported previously, many companies are investing millions of dollars into brain-reading research and development programs.

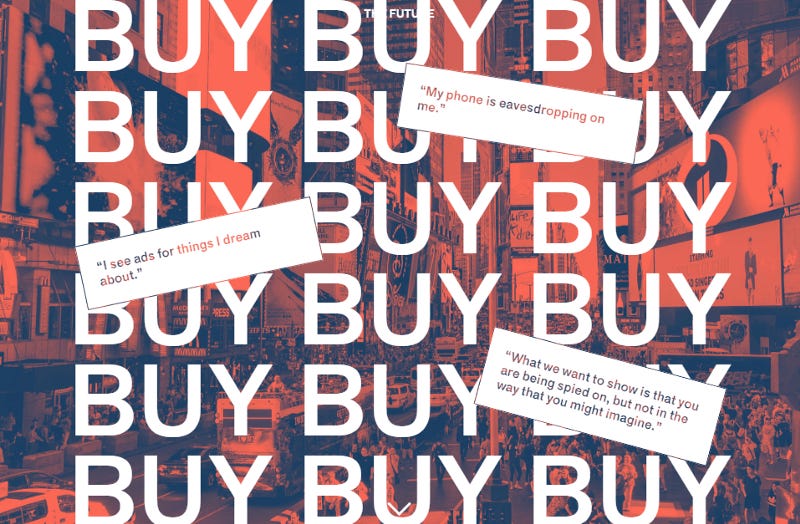

Internet users have long expressed concerns that devices are listening to conversations and are tailoring advertising based on the discussions had. Today, targeted advertising is reaching new levels of obscurity, with digital ads beginning to be described as “becoming psychic”:

Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, has a sister company that isfunding research on BIC devices able to pick up thoughts directly from your neurons and translate them into words. The researchers say they have already built an algorithm that can decode words from brain activity.

Could Facebook be testing new their research through Facebook and subsidiary companies such as Instagram in secret? Would this explain user-reported appearances of ads for products they were thinking about? We already know screens have the ability to manipulate the nervous system.

Social media companies can already use personal data to bring about mass influence of emotions, particularly with pregnancy or suicidal ideation. Could BCI technology push this even further?

Another key player is Elon Musk. Musk’s Neuralink company has developed flexible ‘threads’ that can be implanted into a brain and have a vision to one day allow you to control your smartphone or computer with just your thoughts. Musk wants to start testing in humans by the end of this year.

Not only big tech cashing in on the new phenomenon, reports are beginning to emerge that suggest governments are now incorporating BCI research into various programs.

In China, the government has introduced measures to allow them to mine data from a worker’s brains by having them wear caps that scan brainwaves for depression, anxiety, rage, or fatigue. Companies can decide if they want you to wear an EEG headset to monitor your attention levels.

In the West, the US military is also looking into neurotechnologies to make soldiers ‘more fit’ for duty, including ways to make them less empathetic and more belligerent. Interesting when you consider military deployment during the COVID-19 saga.

In addition, there are also many military-funded research programs to see if decreases in attention levels and concentration can be monitored, as well as hybrid BCIs that can ‘write’ to the brain to ‘increase alertness’ through neuromodulation.

These companies and departments are making fast progress with their plans, and soon, instead of devices reading your thoughts — they might actually do some of the thinking for you.

Brain data is the ultimate refuge of privacy. When that goes, everything goes. Once brain data is collected on a large scale, it’s going to be very hard to reverse the process.

Considering the advancements and ambitions of those involved, as well as how existing laws are not equipped to handle these emerging technologies, experts warn we are likely to witness a scenario emerge that interferes with rights so basic, we may not even think of them as rights.

This includes the ability to determine where we end and machines begin. Sound crazy? Perhaps thirty years ago, but today we are beginning to see examples demonstrating why rights need to be developed protecting humans from alterations to their ‘sense of self’ that they did not authorize.

In one BCI-patient examination, published in Nature and conducted by researchers at the University of Tasmania, ‘Patient 6’ — who had been given a BCI for epilepsy — came to feel such a “radical symbiosis” with the device implanted in her that, she said, “it became me.”

Electrodes had been implanted on the surface of her brain that would send a signal to a hand-held device when they detected signs of impending epileptic activity. On hearing a warning from the device, she knew to take a dose of medication to halt the coming seizure.

Other researchers have also studied computers that monitor brain activity, suggesting BCI devices affect each individual differently from a psychologically perspective.

Don’t take this lightly: Although it is still relatively early days, psychological continuity can be disrupted, not only by the imposition of neurotechnology, but also by its removal. This could potentially lead to future scenarios where companies can essentially own your ‘sense of self’.

In preparation for the rollout of these devices, neuroethicist Marcello Ienca published a paper in 2017 detailing four human rights for the neurotechnology age that he believes need to be protected by law — designed to protect against commercialization of brain data in the consumer market:

The right to cognitive liberty: You should have the right to freely decide you want to use a given neurotechnology or to refuse it.

The right to mental privacy: You should have the right to seclude your brain data or to publicly share it.

The right to mental integrity: You should have the right not to be harmed physically or psychologically by neurotechnology.

The right to psychological continuity: You should have the right to be protected from alterations to your sense of self that you did not authorize.

Currently, no such laws exist that would prevent brain activity from being commercialized, and as the research suggest, the safety of BCI-related devices has not yet effectively been proven.

Ultimately, this discussion is fundamentally anchored in one of the most intensely influential and private of all data streams: human thoughts and feelings. This is serious business.

When learning about the concerns associated, one can quickly see the profound ethical challenge of balancing the potential societal good of mind-reading technology with its truly dystopian shadow.

In the future, if profound technical and legal questions are not seriously addressed before these products are released, the human brain — final frontier of privacy — may not be private much longer.

We only have to look to George Orwell’s concept of the Thought Police in Nineteen-Eighty Four to understand where this scenario could potentially lead with no privacy safeguards.

However, unlike the novel, the real-life version wouldn’t be a fictitious creation from the propaganda department used to instill fear of committing ‘thoughtcrime’. This could be the real deal.

This story was originally published in TOTT News and is republished in A Sense of Place Magazine with their kind permission.

FEATURED BOOKS