The Myth of Black Opal: Lightning Ridge and the Guardians of Fiery Love, A Sense of Place Magazine, 15 March, 2019.

The Myth of Black Opal

Lightning Ridge and the Fiery Guardians of Eternal Love

Mar 15

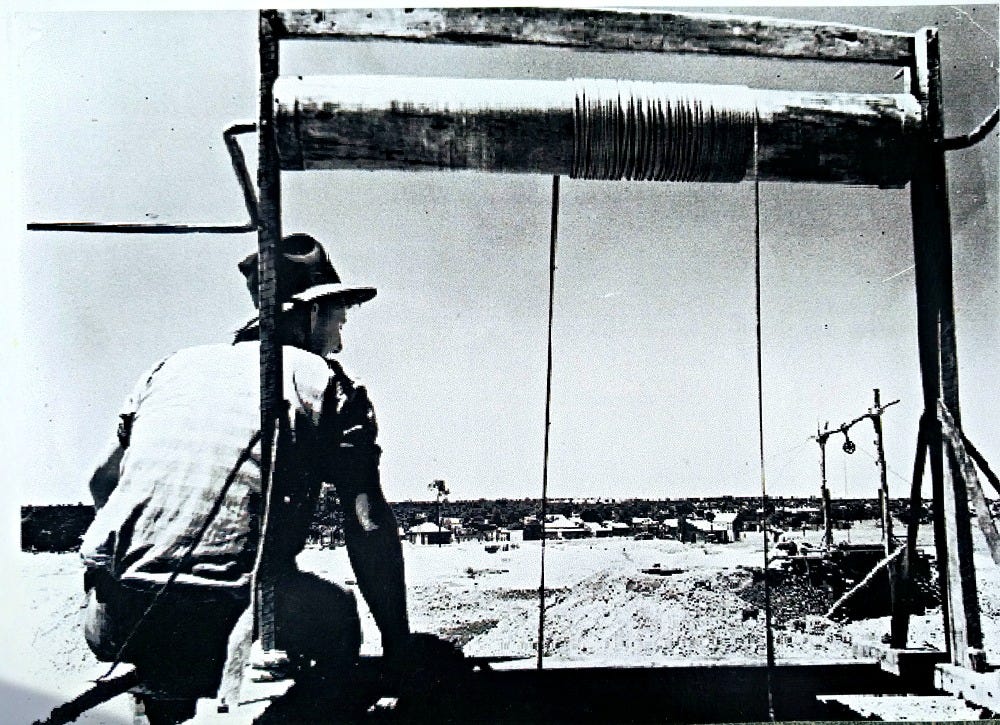

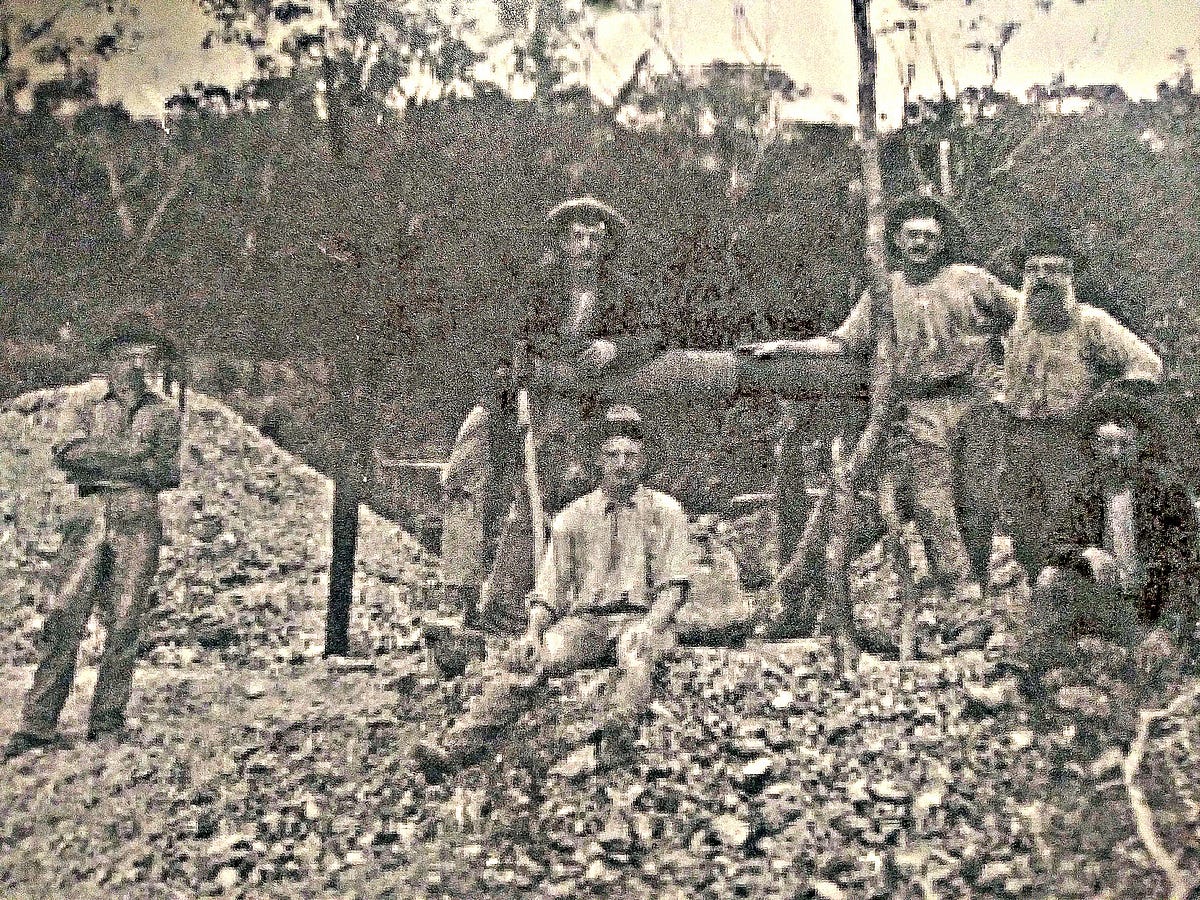

The picture above was taken in 1909, at the height of the what was known as the Three Mile Rush.

The bicycle polisher rigged up in the centre of this picture was being used to rub down opal.

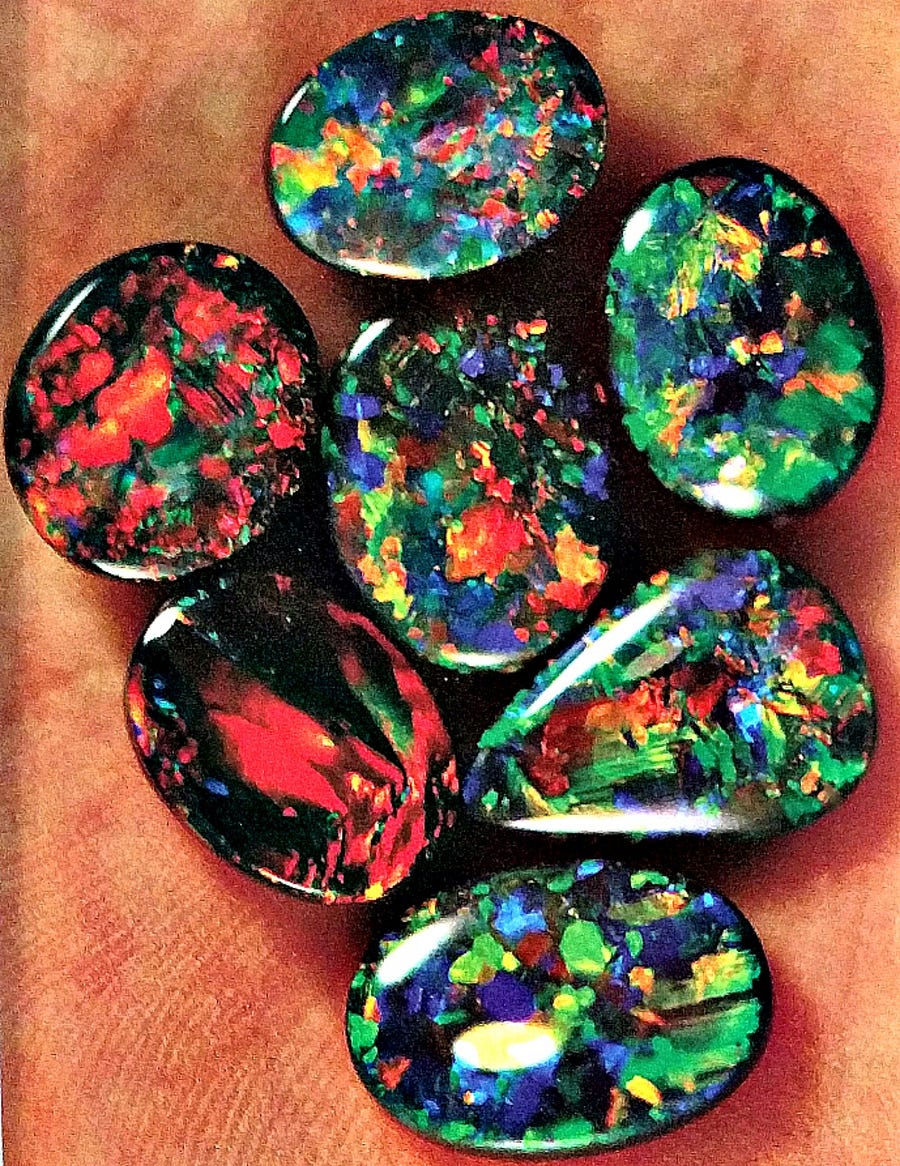

The commercial potential of black opal, said to be the world’s rarest and arguably the most beautiful of all the gem stones, had just been established.

And the Rush was on.

In one of the harshest and strangest places on Earth — Lightning Ridge on the edge of the Great Outback.

This photograph, the property of the Lightning Ridge Historical Society’s collection, is a part of the foundation collection for the new Australian Opal Centre.

It is these photographs, many of them a record of people long dead, which will bring the Centre’s collection of opalized fossils and mining relics alive.

After 20 years of determined campaigning and thousands of hours of volunteer work by locals, finally this month came the announcement that the government will help finance construction of the Centre.

An initial commitment of $20 million from federal, state, and local government, along with substantial contributions from local fund raising campaigns, has been confirmed.

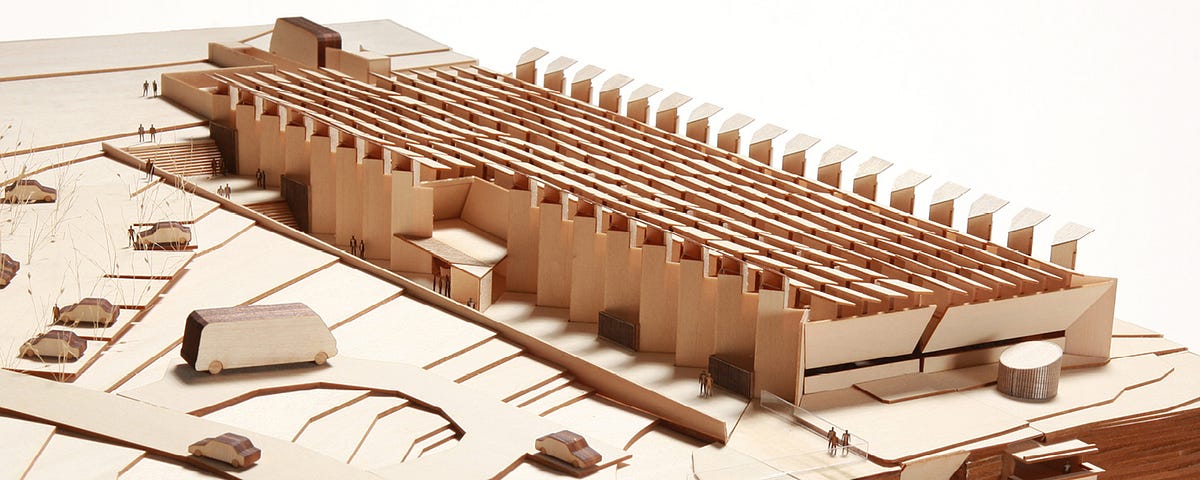

The aim is to construct an innovative style building set in the ground as an energy-efficient, two storey hub for opal education and training, certification, scientific research, art and culture.

The new off-grid building has been designed by world-renowned Australian architects Glenn Murcutt and Wendy Lewin and is expected to reap a slew of awards once completed.

Nettleton

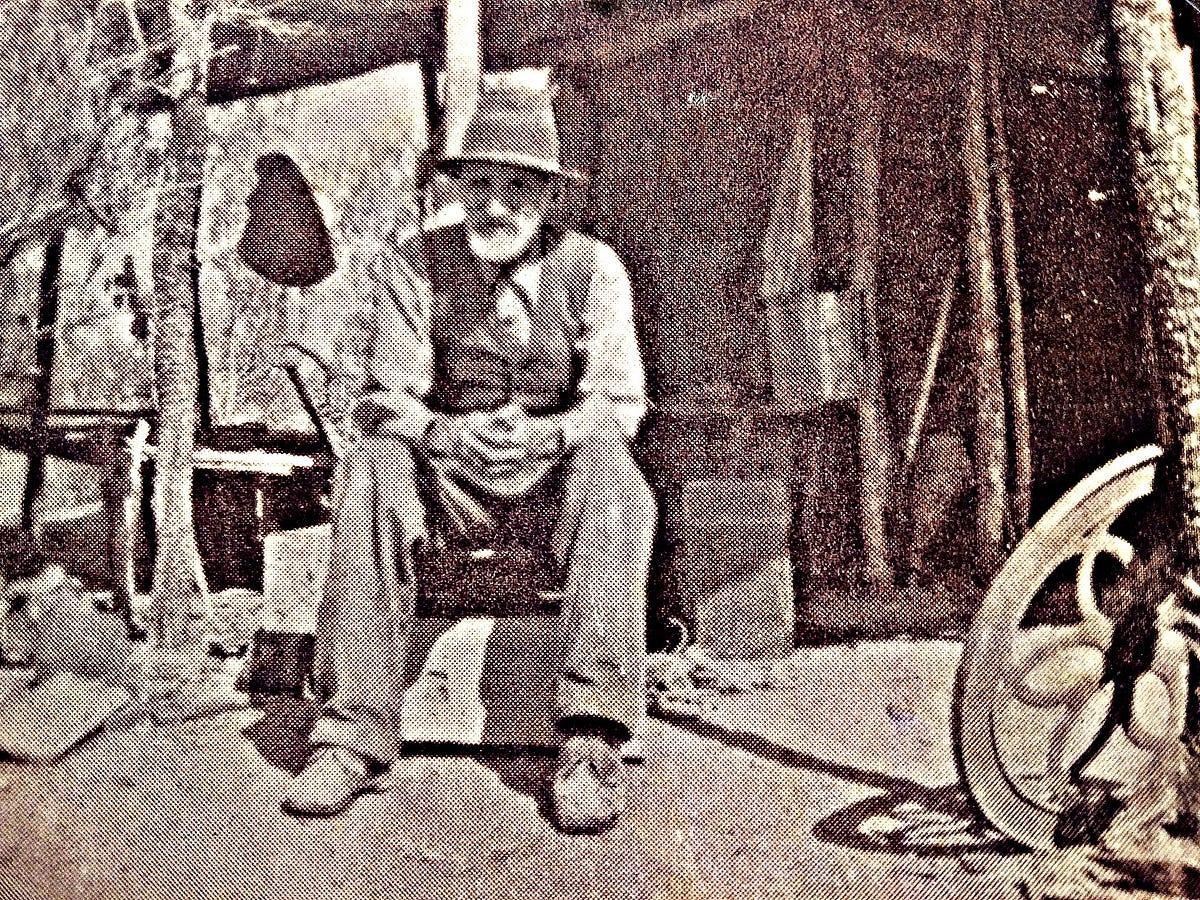

The second settlement on the Lightning Ridge diggings was named Nettleton, after Charlie Nettleton, recognized as the founder of the Black Opal industry.

He had been a miner at White Cliffs, a blistering hot town in the far west of New South Wales.

In 1901, on a visit to the Lightning Ridge district, Nettleton was shown a handful of black stones found by a boundary rider’s wife, Mrs Ryan.

No one had ever seen black opal, and certainly not in nugget form. The woman could see the colour within and was curious as to what it could be.

Charlie Nettleton saw the potential in the unusual opals with their dark body tones.

The first registered opal miner, in 1901, was boundary rider Jack Murray, who worked an adjacent property to the Ryans.

In 1903 Nettleton and Murray walked the 684 kilometres from Lightning Ridge to White Cliffs with the first parcel of black opal ever to be sold.

The conditions were harsh. They didn’t have horses because there wasn’t enough water to keep the animals alive.

The opals were an instant success, and many of their mates followed the pair back to the Ridge.

Nettleton was revered for the rest of his life as the man who recognized the commercial potential of the gemstone.

“He was one of those insular, wandering people the country was full of,” Ms Moritz says.

“He was a prospector, a loner, but was held in great respect because of his knowledge of opal.”

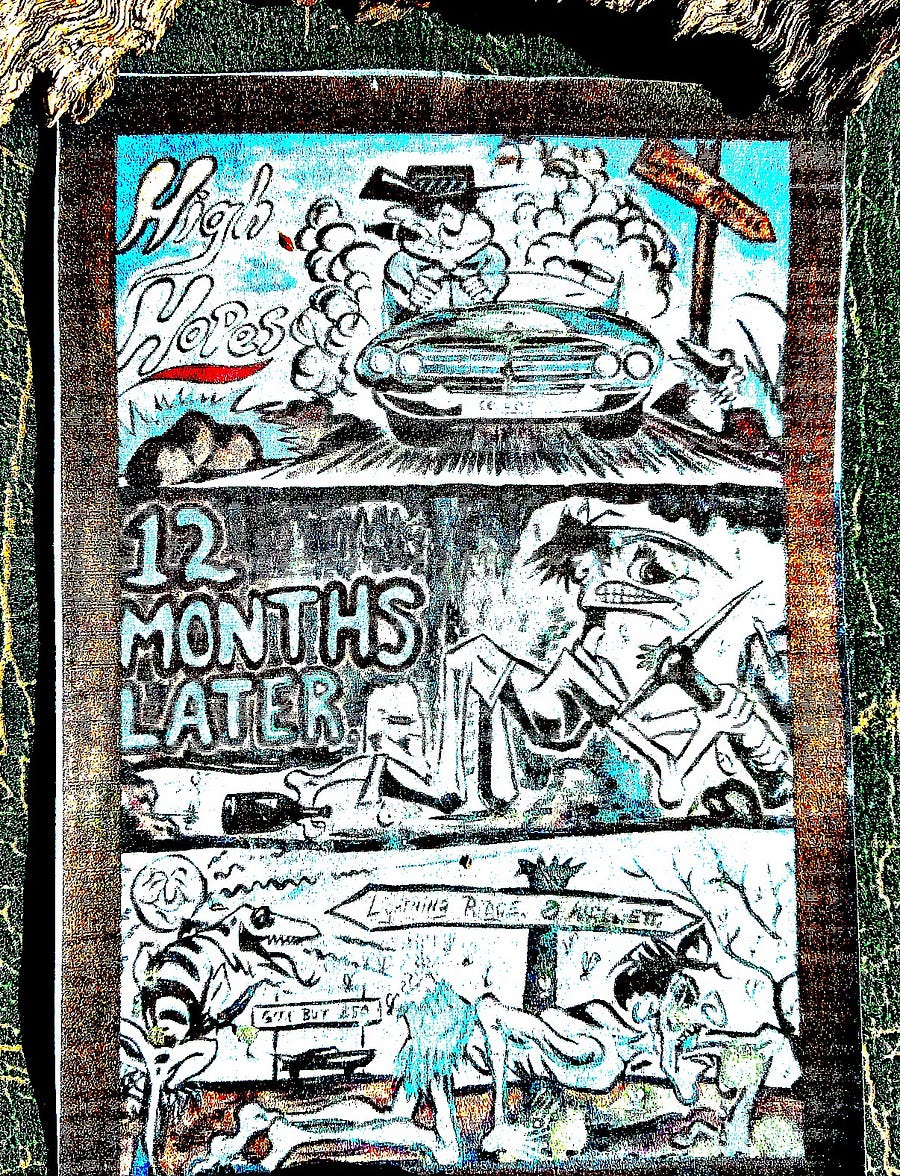

Ms Mortiz says the great allure of the opal fields was only partly the dream of getting rich quick.

People who could fit in nowhere else could fit in here, or at least be left alone.

Many of the people who came here from all over the world were seeking freedom. Their great dream was to be their own boss.

The community was multicultural from the start. All comers endured the hard life and shared the promise of great wealth. As with all get-rich-quick schemes, disappointment and hardship are great equalizers. One in a thousand finds good opal.

They were dreamers. Many of them made fortunes and then promptly drank it all away. And soon enough were back out on the fields in the blistering heat.

More often than not miners just managed to make a living.

Most are passionate about prospecting and mining. And most are simply not suited to city life.

Black Opal: The Legends

The are many stories of the mythology behind black opal. Some may have a basis in Aboriginal legend; more likely they are apocryphal, made up for the tourist trade.

But one legend that has more authenticity than most is the following, which is based on a myth told by Charlie Nettleton to choreographer Dawn Swane.

The story formed the basis for the Black Opal Ballet, which had music performed by well known Australian composer John Anthill and was performed in Sydney in 1961. It featured didgeridoo and a cappella.

The story goes:

Two lovers are saying their last farewells.

Tomorrow the young man, Euroka, must marry a girl, Wyee, from his own tribe. Suddenly, his future wife comes upon them.

Discovered, Amaroo and Euroka, having broken the tribal taboo, flee to escape the death penalty.

They attempt to cross the desert, knowing that the warriors will quickly be on their track seeking vengeance.

Amaroo is soon exhausted.

The native hunters are seen in the distance.

In despair, the lovers appeal to the Spirit of the Wind for help.

A storm of rolling grass balls hides them from their pursuers but they are soon found.

The warriors raise their spears when the Spirit of Lightning strikes.

Together Amaroo and Euroka are imprisoned in a ball of fire, love everlasting.

Thus was the love stone formed, forever after known as black opal.

The Mystical Allure

Opal speaks to people.

The colour rolls as you move.

Every opal is unique. They are like fingerprints.

There is a saying:

Opal chooses you!

And so for many people it would seem to be; these fragments formed in the Cretaceous Period, 120 million years ago — the so-called Age of Dinosaurs.

If it weren’t for opal miners, the opalized fossils being unearthed at Lightning Ridge would never have uncovered.

Because Australian opal is sedimentary opal, not volcanic opal, Australia is the only place in the world with opalized dinosaur bones.

Late last year came the announcement of the discovery of Weewarrasauras pobeni, the first dinosaur to be named in New South Wales in almost a century. It followed a chance discovery of a jawbone fragment in a bucket of opal rubble near Lightning Ridge.

It was a two-legged, plant-eating dinosaur about the size of a dog that roamed the ancient floodplains in the state’s north 100 million years ago.

The name honours the Wee Warra opal field, where the fossil was found, and opal buyer Mike Poben, who saw something special in the specimen and donated it for research.

With the opening of the new Centre, which will give scientists a base from which to further their research, more discoveries are expected.

The Durrington Family were hoteliers who came from Bourke, an inland town then a significant trading centre.

Ted Durrington opened a haberdashery at Nettleton.

And Lunatic Hill became a skyline of windlasses.

“The lunatics who first came here are today’s heroes,” says Lightning Ridge historian Barbara Moritz. “It’s hard to believe now because the diggings around the town are so quiet. Most of the current mining is now an hours drive out of town.

“The remnants of former camps are quiet sentinels to the old timers. Everywhere you look, you see remnants of people’s lives.”

The incredible level of industry required to mine opal in such isolated and harsh circumstances is a subject of comment to this day.

All they had was time. Now we have no time.

Elsie and Hector Jenkins

There is so much history and so many stories associated with Lightning Ridge it is almost impossible to know where to begin.

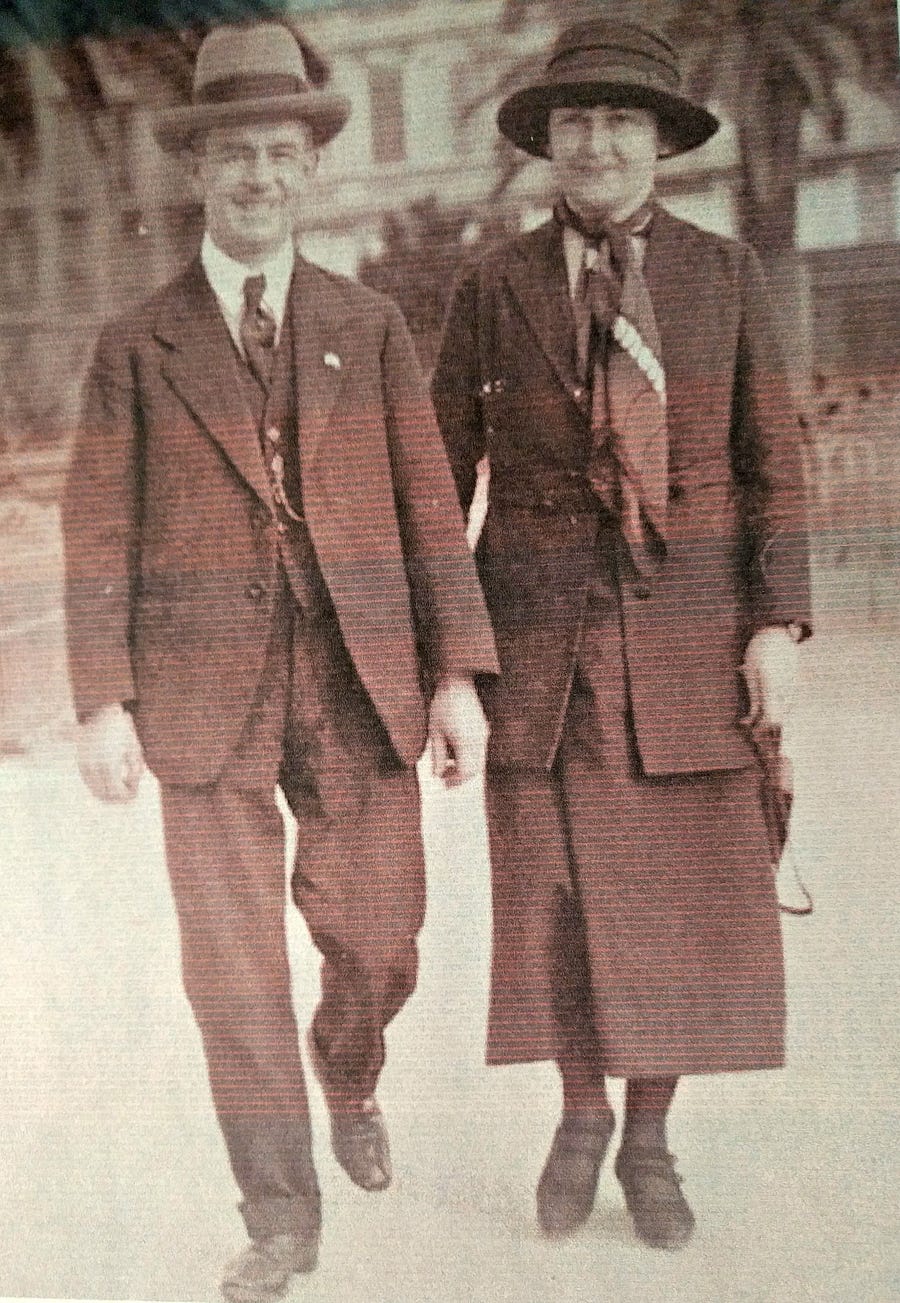

But one of the best known is of Elsie and Hector Jenkins, who did much to spread the fame of black opal worldwide.

The couple were short, barely five foot, and, inseparable as they were, became known collectively as “Tiny Town”.

The adjacent picture is of the couple in Nice, France.

In 1918 Hector and Elsie Jenkins arrived in Lightning Ridge to go mining.

They soon saw that miners needed someone to market their opal. Hector was a gemologist, and he was willing to take on the role of presenting black opal to the world.

They held a major exhibition at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley 1924–25 in the Australian Pavilion. Eighteen million people visited the exhibition, and most of them seemed to come to the Jenkins’ display.

The couple were back for the Grawin Rush from 1926 to 1929.

Hector died in 1957 and Elsie lived on in Alice Springs.

She was known as an astute business woman. The gem display at the back of her dry cleaning business was said to be memorable.

She had racing stables in Adelaide and Melbourne, and other dry cleaning businesses in South Australia.

Her nephew recalls that Elsie owned 29 race horses, two stables in Adelaide, one at Mornington in Victoria, while her opal collection and art collection were substantial.

Elsie “Mah” Jenkins continued to come to Lightning Ridge to buy opal into the 1960s.

She died intestate in 1977.

Her estate was sold by the government to pay what was alleged to be a huge tax debt.

Her gem collection, one of the best the opal industry had ever seen, was auctioned at the Sydney Opera House in the late 1970s.

The Sweep of History

In the early 1900s Lightning Ridge was booming.

By 1910 there were more than a thousand people on the diggings.

The first bush nurse arrived in 1914. In 1916 came the first permanent police.

There were circuses and races — bicycle, foot and horse, both registered and unregistered — in the thriving community.

Mining was done by hand-windlasses using ox hide buckets, one man up and one man underground.

As the Lightning Ridge Historical Society records, many lived primitively and everything was transportable, makeshift and ephemeral.

Just before World War One the government cancelled the commercial leases for shops and other enterprises out on the diggings in an effort to encourage people to move into the New Town, which had been surveyed on land least likely to be opal bearing.

The town was originally known as Wallangulla, an Aboriginal dialect word meaning ‘hidden fire stick’, probably a lightning bolt.

By the 1920s Lightning Ridge was a bustling frontier town.

There were billiard rooms and the famous or more correctly infamous Imperial Hotel, more recently known as the Digger’s Rest.

The Hotel was the heartbeat of the Ridge, and became notorious across outback Australia for wild miners and wild times.

Aboriginal people knew of opals from Dreamtime stories, but they did not mine it. The ridges where opal is found were the highways between the rivers. They settled permanently in Lightning Ridge in the 1930s, after closure of the Angledool Mission to the north and now many of the indigenous living in the area are second and third generation opal miners.

The name was quickly anglicized to Lightning Ridge, but was only officially gazetted in 1963.

Permanent water became available at Lightning Ridge in 1961 when a syndicate of graziers tapped into the Great Artesian Basin, a massive body of water underlying 1,700,000 square kilometres at depths of up to 3,000 feet.

It was only in the 1960s when electricity was put in that the town really took off. Permanent water brought dignity to the struggling community,

Lightning Ridge epitomized the frontier; while fortunes were being made, the postcode was also known for paying less tax than any other area in the country.

Now the government has its fingers through every aspect of life.

To The Present Day

The 1980s and 1990s were boom years in the opal fields.

Miners would gather in the pubs at 10 in the morning having their breakfast beer, with money and opal in their pockets.

Every day held the promise of windfall gains.

The Japanese market could not get enough of black opal.

The town had the highest sales of alcohol and diesel in New South Wales.

And people came from all over the world seeking their fortune.

Today the surrounds of Lightning Ridge remain as insanely harsh as ever.

Two kilometres out of town there is no mains electricity or town water, yet hundreds of people live in makeshift camps, rarely coming into town.

Like many other once thriving country hamlets across Australia, Lightning Ridge is no longer the boom town it once was.

But with heritage tourism it is one of the few country towns with the potential to go forward.

In particular people love the story telling, and stepping back in their imaginations to a simpler lifestyle and genuine camaraderie of earlier days.

Today inland Australia is in the grip of another major drought.

Even the cacti around the Ridge are wilting and dying in the baking heat, while starving kangaroos, in a pitiful effort to survive, chew away at cardboard boxes they find around the camps.

Nor do the often silent fields attract the same adventure seekers and errant souls that they once did. Now only the professional miners survive.

You might be about as far away from the city as it is possible to be, and almost never come to town, but woe betide if a government inspector pulls up outside your mine and you don’t have a running sheet of your day’s underground activities.

“It’s no longer a free-for-all,” says Ms Moritz. “Rules and regulations have taken over, like in every industry and every aspect of our society.

“You must be a business man to manage your opal mining.

“You need multiple certificates from the Mines Department, including safety, environment and mine management.

“We now have Fly In Fly Out miners coming in to support local teams. There is a considerable amount of expensive equipment involved.

“We don’t have the farm hands, shearers and grandpas coming and going during the various seasons, chancing their luck.”

Excessive policing and ludicrous levels of regulation have also banished the hard drinking characters which once filled the local watering holes.

An alcohol limit of 0.05 is strictly enforced, while loners out on camps complain that police will travel 20 kilometres on dirt tracks just to check if they might be growing a marijuana plant.

If you want to see why so many Australians condemn their own country as a Police State, come to a place like Lightning Ridge.

A television program Outback Opal Hunters has captured an audience and led to an increase in visitors to Lightning Ridge.

And with a mix of federal, state and local government funding, the new Australian Opal Centre is rising on Lunatic Hill.

The world’s largest collection of opalized fossils is expected to attract visitors from around the world.

Australian Opal Centre President David Lane believes the project will be a game-changer.

Funding will enable the new Australian Opal Centre to position Western NSW and Australia as the world’s leading destination for opal and fossil related tourism, education, training and certification.

Our new state-of-the-art facility, which is set to inject $94 million and 345 jobs into the NSW economy during construction and $49 million per year thereafter, will be a catalyst for renewed economic and cultural vitality throughout the region.

Well, that’s the dream.

In a place that was always driven by dreams.