The Laughing Lama

On Meeting a Buddhist Master

“Spiritual truth is not something elaborate and esoteric, it is in fact profound common sense. When you realize the nature of mind, layers of confusion peel away. You don’t actually “become” a buddha, you simply cease, slowly, to be deluded. And being a buddha is not being some omnipotent spiritual superman, but becoming at last a true human being.” Sogyal Rinpoche.

There was I, a humble hack on the highways of print, a working journalist, facing a man who was one of the great interpreters of Buddhism in the West, bringing with him centuries of wisdom.

Western scientists, cosmologists, psychologists and doctors were all fascinated.

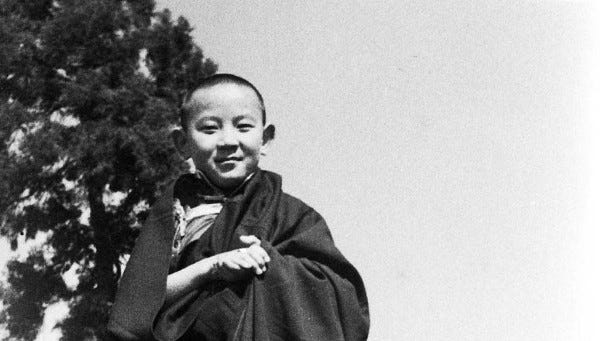

Sogyal Rinpoche was raised in Tibetan monasteries and schooled in the ways of Buddhism from a child.

He is believed by his followers to be the reincarnation of one of the great masters, Terton Sogyal, whose disciples included the 13th Dalai Lama.

Sogyal Rinpoche came from one of the wealthiest families in Tibet; sponsors of Buddhism in the country since the 14th Century.

He was raised by one of the most revered spiritual masters of 20th Century, Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö.

With the Chinese occupation of Tibet, he went into exile with his master, who died in 1959 in Sikkim in the Himalayas.

The Line of Duty

In my normal line of duty as a news reporter on The Sydney Morning Herald I had written a story about Buddhist temples in the west of Sydney.

In those days, the early 1990s, the idea that there were religious institutions and celebrations other than Christian services was a novelty — out there in the Western suburbs of Sydney the elitist news editors and genteel readers of the Herald knew so little about.

Sufficient a novelty for a reporter to be dispatched to investigate with a photographer and a driver, out there in those wild, unknown reaches.

And hopefully return with a yarn and a picture good enough to fill that gaping maw, a large daily broadsheet desperate for news.

Newspapers are like bonfires. They burn stories.

In those days, 1993, with a nascent internet, print was king and there were many pages to fill. It was an entirely different world, before the advertisers deserted en masse and news came to be read on devices.

Face the Press

A few weeks after the publication of that little yarn someone from Australia’s multicultural public broadcaster SBS rang me up, purring compliments about how sensitively I wrote and what great knowledge of Buddhism I displayed.

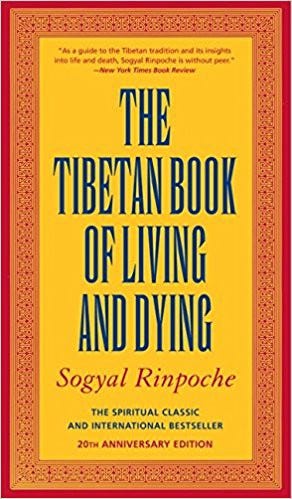

They asked me to go on their show Face the Press as part of an interview panel for someone or other called Sogyal Rinpoche, who was touring the world promoting his book The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying.

Cynicism is a reporter’s stock in trade.

We are always being called into a situation because someone thinks publicity will serve their ends, whether it’s to sell a product, bolster electoral opportunity, wreak vengeance on an enemy or find justice in exposure.

My children were young. My partner was a nightmare. My bosses were a pain in the derriere. And in some deep sense: I was not well.

Harried and short of time, I begged off, telling them the truth. I had no special knowledge of or background in Buddhism. All I had done was pick the brains of the Buddhist Information Service and their particularly able frontman, Graeme Lyall.

I simply was not qualified. There were plenty more people better suited.

I insisted. They persisted.

In the end the Chief of Staff ordered me to do it.

Most reporters have neither the time nor the inclination to read the works of the authors they interview.

But being a literary type of fellow, and in preparation for the interview, I read the book. And a fascinating read it was.

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, written by Buddhist master Sogyal Rinpoche, immediately assumed, upon first publication in the early 1990s, status as a great spiritual masterpiece.

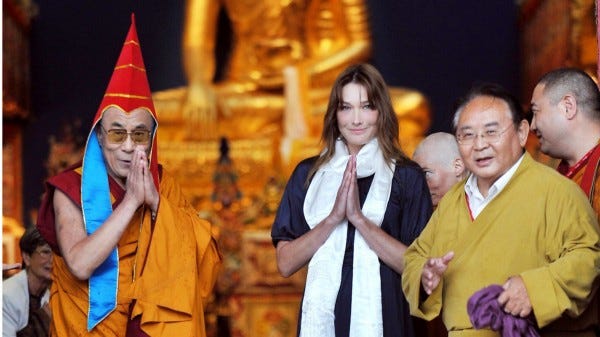

It was republished with a Forward by the Dalai Lama.

With rapidly evolving circumstance facing down a sickness of heart, mind, culture and belief, a sickness of the world and a sickness of the spiritual realm, perhaps there could be no more relevant text.

In his Forward the Dalai Lama wrote:

As a Buddhist, I view death as a normal process, a reality that I accept will occur as long as I remain in this earthly existence.

Knowing that I cannot escape it, I see no point in worrying about it.

I tend to think of death as being like changing your clothes when they are old and worn out, rather than as some final end.

Yet death is unpredictable: We do not know when or how it will take place.

So it is only sensible to take certain precautions before it actually happens.

Naturally, most of us would like to die a peaceful death, but it is also clear that we cannot hope to die peacefully if our lives have been full of violence, or if our minds have mostly been agitated by emotions like anger, attachment, or fear.

So if we wish to die well, we must learn how to live well: Hoping for a peaceful death, we must cultivate peace in our mind, and in our way of life.

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.

From the text, from life

I had a set of rubber people questions — after all we were talking life and death here — and The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying was no ordinary book.

None of the normal questions applied.

Sogyal Rinpoche’s stated aim was to inspire a quiet revolution in the whole way we look at death and care for the dying, and the whole way we look at life, and care for the living.

The event was, well, gracious.

Rinpoche was highly intelligent, charming, infinitely wise, commanding of respect, but at the same easy to interview. The conversation flowed.

“Death is like a mirror in which the true meaning of life is reflected,” he said. “What is important is the way you live.”

And I believed him.

At one point I asked:

“So this is what you mean when you say, if you are not prepared for death, you are not prepared for life?”

Sogyal Rinpoche’s face lit up with an expression of pure delight.

He had just spied before him that rarest of jewels — a journalist who had actually read his book.

After the taping the Buddhist Master laughed and held my hand as the small band of journalists made our way towards the lifts.

In the background were devotees who clearly revered him as a living god.

I thought about him for many days afterwards.

At the time I felt like I had just interviewed Jesus Christ or the Buddha, an entity from another time and place, a reincarnation, an old and very wise soul.

Vignettes

Childhood

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying is not only full of wisdom, but clear in a way spiritual text really are. As I pontificated at the time, “It does not invite the normal critical posturings.”

The descriptions of childhood are very evocative, the personal anecdotes illuminating, the broad knowledge of Buddhist text unparalleled. It is full of vignettes.

MY OWN FIRST EXPERIENCE of death came when I was about seven.

We were preparing to leave the eastern highlands to travel to central Tibet.

Samten, one of the personal attendants of my master, was a wonderful monk who was kind to me during my childhood. He had a bright, round, chubby face, always ready to break into a smile.

He was everyone’s favorite in the monastery because he was so good natured.

Every day my master would give teachings and initiations and lead practices and rituals.

Toward the end of the day, I would gather together my friends and act out a little theatrical performance, reenacting the morning’s events.

It was Samten who would always lend me the costumes my master had worn in the morning.

He never refused me.

Then suddenly Samten fell ill, and it was clear he was not going to live. We had to postpone our departure.

I will never forget the two weeks that followed.

The rank smell of death hung like a cloud over everything, and whenever I think of that time, that smell comes back to me.

The monastery was saturated with an intense awareness of death.

This was not at all morbid or frightening, however; in the presence of my master, Samten’s death took on a special significance.

It became a teaching for us all.

A human being is part of a whole, called by us the “Universe,” a part limited in time and space.

He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness.

This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest us.

Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circles of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature.

Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

The Bad Boy of Buddhism

In later years scandal enveloped the Master.

Headlines described the accusations:

Sogyal Rinpoche and the abuse accusations rocking the Buddhist world

Punching. Emotional abuse. Eye-popping sexual misdeeds. The accusations made against Sogyal Rinpoche — a key lama in the uptake of Buddhist principles by the West — have rocked devotees, including many in the top echelons of Australian business.

Sydney Morning Herald, David Leser, 1 December, 2017.

Sexual assaults and violent rages… Inside the dark world of Buddhist teacher Sogyal Rinpoche

Within the Buddhist community, however, Sogyal Rinpoche has long been a controversial figure.

For years, rumours have circulated on the internet about his behaviour, and in the 1990s a lawsuit alleging sexual and physical abuse was settled out of court.

The UK Daily Telegraph, Mick Brown, 21 September, 2017.

Sogyal Rinpoche went into retreat and then retired.

In a message to his followers he wrote:

Don’t ever forget the most important thing of all: these incredible teachings that we have shared together.

We have lived through such extraordinary moments together, where we all experienced the very deepest aspect of our bodhichitta, our buddha nature, the ultimate nature of mind.

How can we not remember?

We need to keep these teachings constantly in our minds and to hold them, so they will last long, long into the future.

They can not die.

Whatever did or did not happen, what I remember most about the author of The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying is the way he held my hand as he beamed a kind of intra-dimensional delight.

And we made our way to the lifts.

Adapted from the upcoming book Hunting the Famous.

Devote the mind to confusion and we know only too well, if we’re honest, that it will become a dark master of confusion, adept in its addictions, subtle and perversely supple in its slaveries.

Devote it in meditation to the task of freeing itself from illusion, and we will find that, with time, patience, discipline, and the right training, our mind will begin to unknot itself and know its essential bliss and clarity. Sogyal Rinpoche.

This is an extract from the upcoming book: