The Kashi Vishwanath Express: The Photography of Russell Shakespeare

Apart from walking, one of the slowest ways to travel the 794 kilometres from New Delhi in the state of Uttar Pradesh to Varanasi on the Ganges is the Kashi Vishwanath Express.

Multi-award winning Australian news photographer Russell Shakespeare first caught the train in 1987 as a young, wide-eyed twenty something who had never been to India before.

“It is almost a ritual now, every year I go back I have to catch the Kashi experience,” he says. “For someone who hasn’t been to India before, it drives them a bit mad. On parts of the route, it can be absolutely jam packed. If you’re a tourist accustomed to five star travel, it’s definitely not for you.

“It is basically the mail run. It stops everywhere. There are 32 stops.

“Its average speed is 46 kilometres an hour.”

The famous train is named after the Kashi Vishwanath temple in the sacred city of Varanasi, where Indians believe they can escape the cycle of reincarnation.

Kashi Vishwanath Temple is one of the most famous temples in India, dedicated to the powerful Hindu deity Lord Shiva, destroyer and transformer in the karmic cycle.

I would always reserve a seat and a bunk. That seat is meant for three people during the day, but until sleeping time it is not unusual to have eight people crammed onto that one seat.

Just work that out.

Out the Window India Breathes Infinity

Russell Shakespeare: The beauty of the Kashi Express is that it departs New Delhi just before lunch and arrives in the incomparable Varanasi just before breakfast.

Normally I would have just arrived the night before into New Delhi from Australia.

I have worked as a newspaper photographer most of my life. It is frantic, often demanding, often unrewarding work.

You deal with a lot of death. And rotten editors.

The thing I love about getting the Kashi Express is that it is like a slowing down again, reconnecting with India.

For five or six hours you are travelling through India in daylight. It is wonderful for me to travel at a slow speed, to be reabsorbed into India.

One time I did take an express train, but it was just after drinks, so I got this carriage full of really drunk men, and it was a shocking experience.

After that I decided I would go back to my old habits, and catch the slow train, which is what I’ve been doing ever since.

Changing Paths: One True Direction

The Kashi Express actually changed my whole direction in photography. It changed everything for me.

At 27 years of age, I went to India, it was my third trip. And I went with every piece of equipment that I could afford, the latest SLR, a zoom lens, a kit full of gear that was very heavy.

About three months into the trip, I had been travelling in various parts of India, and I caught the Kashi Express back to Varanasi.

The difference was I was a bit sick at the time. I got into a super-crowded carriage. You are pressed literally like sardines in a can, fighting your way to get through the pressing bodies to your seat.

For the first time in my life I put all my gear on the top bunk, they turn into beds at night, and I was travelling with friends.

Five minutes later, I said to myself, what are you doing. You always keep your cameras with you.

I checked, and two thirds of my equipment was gone, including one of the latest, very expensive Nikon cameras.

Five thousand dollars I had saved working as a carpenter while I was going to art college.

It had taken me a few years to save that money and it was all gone. The whole lot.

All that was left was one Nikon FM2, the most basic camera. Completely manual. And a 28mm lens.

Simplifying Life Simplifying Art

It was like the shackles had been pulled off. I wasn’t burdened with equipment. I had to work with what I had.

I have never bought a zoom lens since. I’m not joking, it changed the entire direction of my photography.

Losing all that equipment and being left with one wide angle lens, in Photography 101 a zoom lens keeps you away from your subject because you can zoom in. It distances you from people, and that was what I was using for a lot of my work. You have to remember I was young. I was still learning about photography.

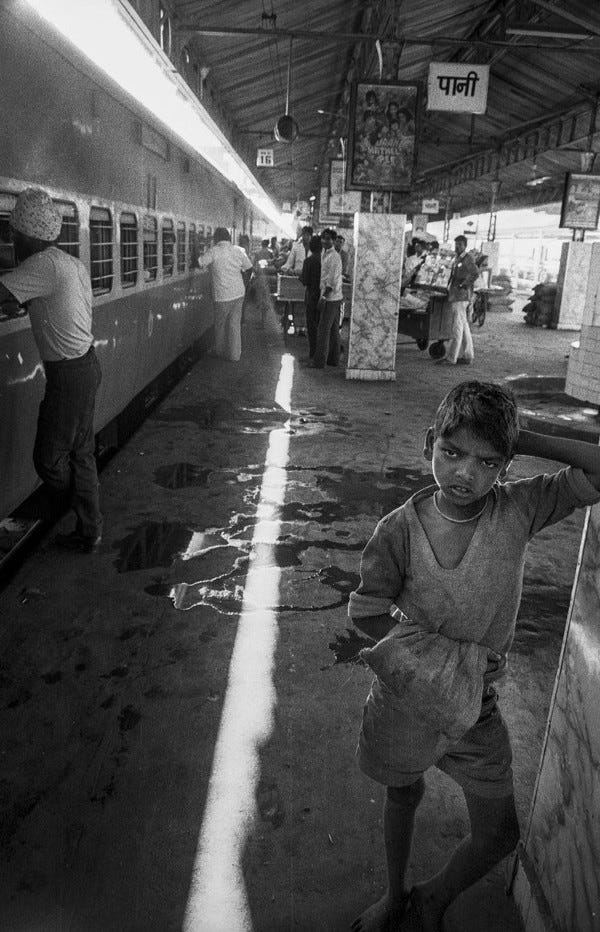

Being left with a wide-angle lens meant that I had to be a couple of metres away from someone.

It forced you to connect with that person.

By doing that, it meant that I had to approach people and they would know I was photographing them, rather than shooting from a distance.

To this day, for all my documentary work, I never use a zoom lens. It is a forced intimacy which in the end is wonderfully revealing of the person’s personality and motives.

As one of the pioneers of photojournalism Alfred Eisenstaedt said:

It is more important to click with people than to click the shutter.

Through A Window Darkly

In the second and third class carriages you get all the performers and hawkers, continuous chai men, samosa sellers, drinks, there is a continuous lineup of people at every station.

There’s a 1995 American Western called Dead Man starring Johnny Depp, which reminds of the Kashi Express. People are constantly getting on and off the train, and those people vary according to the landscapes through which you pass, as if they were part of them.

As you make your way through to Varanasi, people are getting off, new ones are coming on, it is a fascinating blend of people.

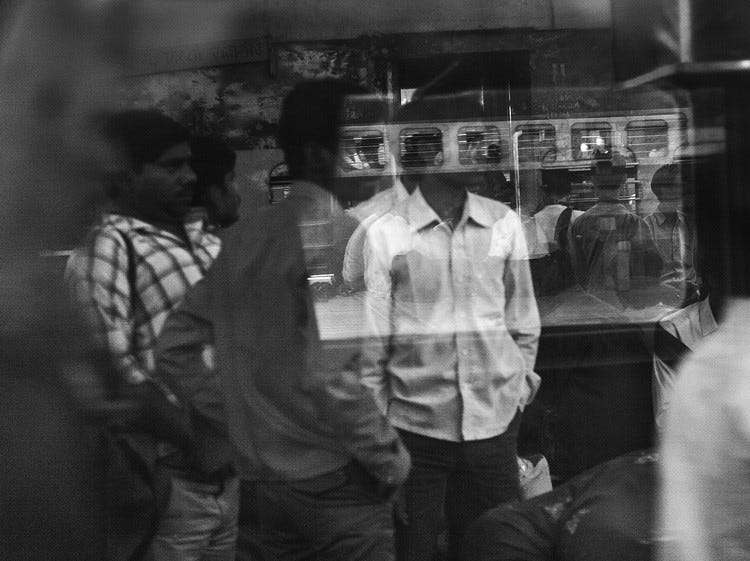

I became really interested in reflections.

This is some of my later work.

I moved in a sense over the years from being very specific in my art photography, the work I do for creative fulfillment rather than as part of a daily working assignment, to loving a sense of the abstract.

The other great thing about catching trains, is for that period of time, you are usually with an Indian family, for eight to ten hours in many cases.

You can either sit there and read your book, or interact with them.

And that is one of the things I really really loved. Trying a bit of Hindi, and learning a little bit more about that culture.

In the modern day and age, when everybody is on Instagram, I have made friends I am still in contact with.

They are curious, friendly, interested in why you are travelling and what you can see through your camera, because for them it is just ordinary, everyday life.

The God of Small Things

So much of India is pre-industrial.

It is village life.

You look out the window, and you see a world that has barely changed in a thousand years. You get these wonderful little moments, and then they are gone. Whether it is kids playing a game of cricket, or old men sleeping on charboy beds.

Or villagers gathering together the cow pats for the evening fire.

When you are going past those little villages, you are seeing life happening out on the street. Because the train is happening everyday, it is just another feature in their landscape.

Life just goes on.

It is those gems of lost time, sublime and delightful as they are, which makes the discomforts of Indian train travel worth every last second. If you are on a super-fast train, all those moments are lost, just a blur out the window.

And if you fly, they are just a speck from the air.

There is Nowhere Else on Earth like India

I always like arriving in Varanasi just before dawn.

There is nowhere else on the planet that is anything like India.

Much of the modern world is familiar, you are in another suburb, another office, in yet another traffic jam. But India just isn’t like that. There is absolutely no mistaking where you are, it is drenched with atmosphere.

And of course there are the smells.

You certainly don’t get that flying.

That is another thing that I absolutely love, the sensory part of the travel.

When you are in the city you are just smelling fumes and pollution which burns your eyes.

On various parts of the journey you pass dump areas, so that you get that smell.

And as you get out the city, you get that distinctive smell of the Indian fires, made from cow pats. It is basically people just cooking their meals, but that’s what they are cooked on.

Not to mention, at every station the incredible smell of food.

The hawkers come up to the windows with all this food, while the tea sellers chant Chai, Chai, Chai. I just love it.

These days I can afford to catch the plane, which takes just over an hour, but I just don’t.

For me, catching the Kashi Express is like I’m coming home. It has soul.

Russell Shakespeare’s work has been published in many national magazines and newspapers, including Gourmet Traveller, The Good Weekend, TIME Magazine, the Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, and in books by the Magnum Foundation, Australian Geographic and The Museum of Brisbane.

He has won the Walkley Award for best news photograph of the year, Australia’s highest award for photojournalism.

His works have been collected by the Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane and The National Portrait Gallery, Canberra.

A collection of his work can be found at his website here.

All photographs used in this piece are Copyright to Russell Shakespeare.

To purchase or make use of his work please contact him through his website.

John Stapleton first made money out of writing in 1974. He worked as a staff reporter for The Sydney Morning Herald from 1986–1994 and for The Australian from 1994–2009 and continues to work in the field.

A collection of his journalism can be found here.

RELATED ON MEDIUM:

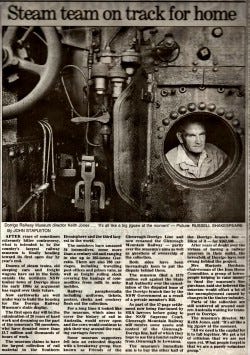

Previous Collaborations between Russell Shakespeare and John Stapleton on The Australian newspaper include:

Art blends best of black and white

The Australian

13 August, 1994.

Logging rules whittle down a dying town

The Australian

8 April, 1996.

The Australian

15 April, 1996.