The Destruction of the Pilliga: Australia's Most Fabled Forest

By Paul Gregoire: Sydney Criminal Lawyers Blog

Much of Sydney's housing of the 1950s was built from the region's prized cypress pine; before the timber industry was progressively, and controversially, closed down through environmental activism and safety regulations impacting the dilapidated but intensely atmospheric sawmills.

Now the forest faces an entirely different challenge, as one of Australia's leading independent writers Paul Gregoire reports. Here he interviews the makers of the documentary The Pilliga Project, which has recently been made readily available on YouTube.

Images in this text are screen shots from the film.

In the midst of a pandemic, just half a year after a bushfire destroyed large tracts of land, and not long following a years-long drought having devastated the country’s southeast, PM Scott Morrison stood before the nation to unleash his gas-fired recovery vision in September 2020.

This plan involves opening up five new gas fields, including one in Narrabri, which the NSW Planning Department conveniently signed off on just a fortnight later.

This saw the greenlighting of 850 coal seam gas (CSG) wells set to be drilled right across the Pilliga Forest.

The Pilliga sits atop the Great Artesian Basin, one of the largest freshwater reserves in the world, which millions of people rely on. Indeed, the forest is a critical recharge zone for the water source.

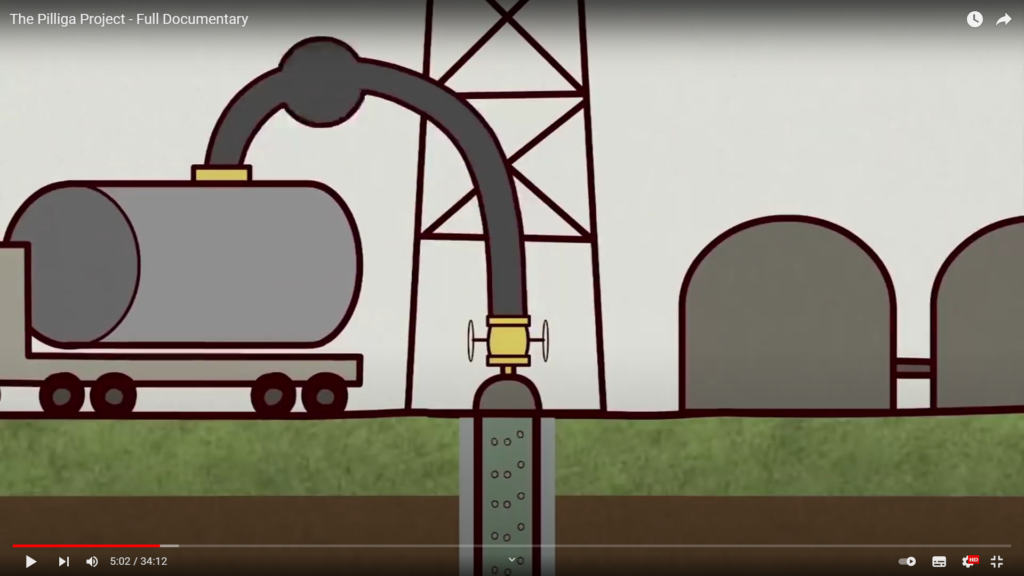

However, Australian energy company Santos plans to drill the wells straight into basin to get to the gas below.

The proposed Narrabri gas field is also situated in the centre of the Murray-Darling Basin: an area recently devastated by drought.

The region is where 50 percent of Australia’s food is produced, and it could soon be the storage site of millions of litres of toxic water produced via the CSG process.

Kicking against the plans

So, that’s where the Pilliga Project comes in. It’s an independently funded and produced documentary that serves to alert the broader Australian community about the proposed destruction of the forest, the further heating of the planet, and the loss of food and clean water.

Documentary producer Shannan Langford Salisbury, director Natalie Haddad and the rest of their team launched the Pilliga Project at an event hosted by Extinction Rebellion Sydney on 21 January.

And the film’s now available for all to watch online.

https://youtu.be/cWXJzPYD9UY

The Pilliga Project explains how the Narrabri gas project will devastate the local area and beyond. And it also provides shocking details of how the CSG grid that will destroy the Pilliga is also set to spread right across the state, while the broader gas-fired recovery grid, covers the entire continent.

The dispossession continues

The Narrabri gas field sits on Gomeroi Country. At last week’s launch, Gomeroi woman Aunty Deborah Briggs outlined what the project would mean for her people if it’s not stopped.

“Gomeroi is a matriarchal society. Yinna-women hold the lore over our water supply. So, we’ve got staunch Gomeroi women that are standing up. It’s a tough job, because there’s a lot of bullying,” Aunty Deb told the audience.

“My ancestors always lived in and utilised this forest and the water connected.”

The Gomeroi sovereign elder further advised that her people have been struggling against the gas proposals for the last 12 years. And she said court action is underway that’s attempting to strip “Gomeroi sovereign rights” and take the Pilliga from them.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Pilliga Project producer Langford Salisbury and director Haddad about what drove them to make the documentary, the way Santos is operating in the local town, and their thoughts on Morrison’s mid-pandemic gas plan.

Pilliga Project producer Shannan Langford Salisbury and director Natalie Haddad

Both the NSW and federal governments have greenlighted the Narrabri gas project. You’ve just released a documentary focusing on it.

So, why did you two decide to make a film about the proposed gas field in the Pilliga?

Natalie: I didn’t start out wanting to make a documentary about gas. I was invited to go to the Pilliga for the forest itself.

I grew up in cities and I’d never seen true untouched wilderness before. So, it was really beautiful seeing a healthy forest like that.

But once we were in there, we saw a contamination event: poison was leaking into the forest. And it was quite striking that in such a beautiful place just a few gas wells were causing so much destruction.

So, once I learnt that gas wells were going to built right across the entire forest, and it was going to destroy it, I knew this was a story that I wanted to tell, because it’s so shocking.

And I knew that if people heard what was going on, it would be just as shocking to them.

Shannan: I came at it from a very different angle, as I used to work for the Murray-Darling Basin Authority.

So, I would spend my days looking at maps of the whole Murray-Darling Basin, which the Pilliga is in, and what I learnt was absolutely devastating.

I got the opportunity to go up to Narrabri with some climate activists meeting with Gomeroi elders. Then Nat and I went back to go into the forest.

I knew about the Namoi River and how cotton farming and fossil fuel projects had affected it. In 2019, while I was working at the Murray-Darling Basin Authority, that’s when the Darling ran dry for hundreds of days, and the Namoi was damaged.

For me, it’s all about water, and how we save ourselves, because there’s millions of people, millions of animals and millions of hectares of land at stake.

The documentary raises issues around how Santos is going about courting the local community in the town of Narrabri.

What does this involve?

Natalie: For any community anywhere, water is the centre of everything. And if you threaten a community’s water, they’re going to fight back and defend it.

But what Santos does is, before they begin drilling, they need the community on side, so they start funding essential services. They fund hospitals or schools, or they’ll do something like sponsor footy games.

These are essential services that every community should have, regardless of a gas company being there.

The company comes in and funds them, so that when they’re operating, the community as a whole is less likely to do something about it, because their families rely on these services.

It’s in your interest to keep Santos happy, as Santos will threaten to remove these services if they’re not allowed to operate.

So, it holds these communities hostage, as if they want these services, then they must approve of the operation.

The effects on the water won’t be seen on farming for 20 or 30 years, but you can see the effects it’s having on the forest straightaway. So, that’s a long-term issue of how sustainable it is for the community.

But in the short-term, when gas rolls through there is a lot of employment and it is beneficial for the community. But it’s at a price.

The question is whether it’s worth sacrificing your water because once it’s gone, there’s no community left. There will be no Narrabri.

That’s the price that they’re paying in the long-term. It’s through no fault of their own. It’s very predatory.

Shannan: It’s definitely a predatory and coercive relationship. The town has already seen Santos saying that it can pull services, unless it does what the company wants.

So, it makes people complicit in their own destruction – the destruction of their town and their community – because they won’t stand up when things go wrong. And they’re going to go wrong.

And what happens further down the track after a project is over?

Shannan: Once a project is done, they’ll leave and then you’ll have a ghost town. And there are plenty of those around Australia.

Once the industry is gone, the town is left as a shell, and people move out.

All that’s left is a devastated environment. You can’t go back to previous production on the land. So, it’s terrible for everyone involved. The land and many people are poisoned.

As mentioned, the Narrabri gas project is situated on Gomeroi Country. The documentary prominently features Gomeroi people discussing what they’re facing.

From your understanding, what does this project mean for the Gomeroi Nation?

Natalie: The project could destroy their entire history and culture, and the land that they’ve protected since humans first existed in Australia.

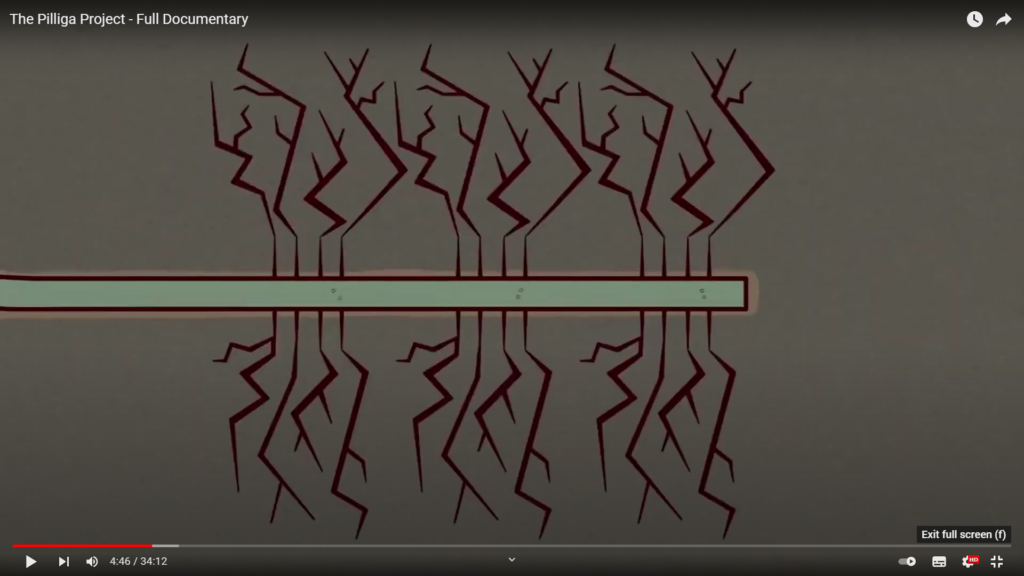

It will destroy the forest. Even though it’s not being bulldozed to the ground, the forest is being fragmented with roads, pipelines, and wells.

Forest biodiversity and ecosystems rely on the whole bush and when you fragment it, the way that the forest operates is changed.

That’s not even getting into the water impacts. The entire forest relies on the water table, so, if it drops, it will kill the forest.

These are sacred sites and, once they’re destroyed, they’re gone and there’s no getting them back.

Companies are willing to put all this at risk for profit. It’s human history that they’re destroying.

Shannan: Water is life. Once you start impacting that, then you’re slowly going to impact everything that relies on it.

So, you’re killing life when you start in on the forest. You are killing the Gomeroi people, their land and their history, and then it’s going to spread further out.

The impact is where you have no water, you have no life. That’s really scary.

Gomeroi elder Aunty Deborah Briggs speaks at the documentary launch

The Narrabri gas project had already been in the works by the time the prime minister announced his gas-fired recovery out of the COVID pandemic in 2020.

What are your thoughts on the way Morrison unveiled the gas expansion proposal to the community mid-pandemic?

Shannan: The gas-led recovery is the Liberal Nationals last ditch attempt to milk the fossil fuel industry.

They know that it’s the end, and instead of making plans towards renewables that will help us in the future, they’re focusing on getting this last bit out.

The way that he did it in a pandemic was such a slimy move. Everyone was in lockdown, and they weren’t able to say that the way out of a pandemic is not more ecological destruction.

From my background in animal science, I know novel diseases, like COVID, come from people encroaching on wilderness. So, if you continue to go into parts of the wilderness where people haven’t spent a lot of time, then you’re going to get more novel diseases.

It’s madness to say let’s destroy more wilderness, which will bring more diseases, and that will somehow get us out of a pandemic.

Natalie: When he announced it, we couldn’t go out and protest. The news barely touched upon it. I had to actively look for it. That was done on purpose.

This is something that’s going to affect so many people for so long. But the news barely mentioned it.

This could have been a golden opportunity to fast-track to renewables. It could have set Australia up for a renewable future. That’s what you’re supposed to do in times of economic crisis.

But they went the other way to milk the last money out of fossil fuels.

The documentary also makes the point that the Narrabri gas project has much greater implications than the 850 gas wells that are slated to be drilled in the forest region and its surrounds.

Can you describe what the wider impact will be, and what it will mean for the environment and the climate?

Natalie: The project is going to be larger than the 850 gas wells. That’s just what’s currently approved.

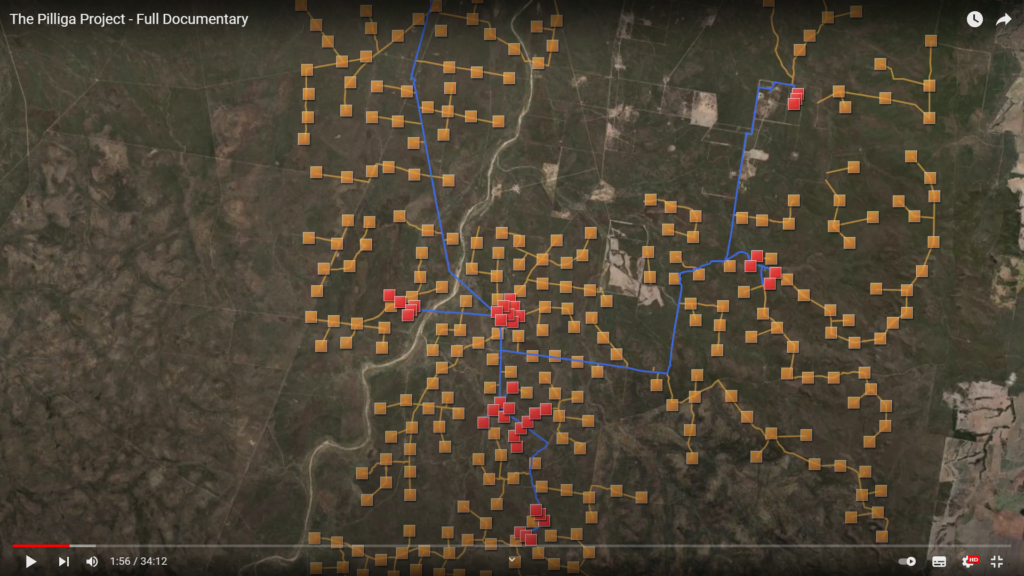

As you see from the maps shown in the documentary, there are exploratory licences for all across NSW. It goes from the Queensland border, all the way down to Newcastle. It’s all gas fields, and the Pilliga is at the centre.

It’s not just in NSW though, it’s across Australia. It takes in the Northern Territory and South Australia. It will be just one massive gas field across the entire country.

The wells cause most of the damage underground. It happens to our water. When you destroy the water table, it’s gone.

This gas project is in the recharge zone of the Great Artesian Basin, which is how it’s able to refill itself. So, once that’s destroyed, you affect the rest of Queensland, with areas that don’t have any gas fields on them.

Water connects everything, and when you destroy it, it destroys everything else.

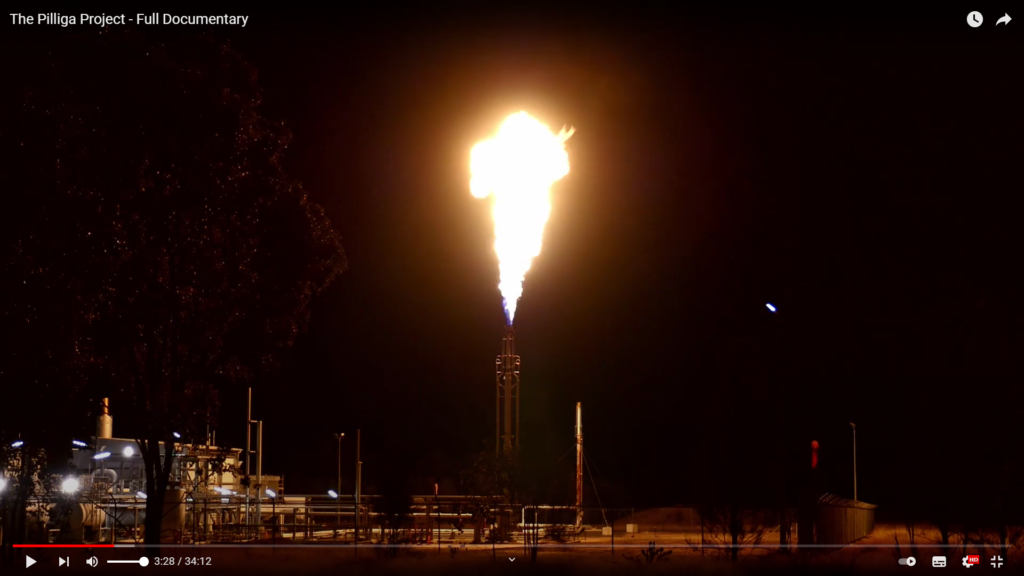

Then there’s the methane that’s going to release.

The industry has done a great job at marketing gas as a cleaner fossil fuel, but while it releases 50 percent less carbon dioxide, it releases unknown amounts of methane.

We don’t know how much methane is being released by a lot of these gas fields, because you’re not required to monitor it in Queensland.

There are some gas fields in the US that have an 8 to 10 percent methane leakage rate. And you only need 3 or 4 percent for it to be just as polluting as a coal mine.

But the damage of gas on the ground is invisible. It’s not as visually scarring as coal. It’s subtle. You can’t really see it until it’s too late.

Shannan: The Pilliga is on the edge of the Great Artesian Basin. And it’s right in the middle of the Murray-Darling Basin, which is where more than 50 percent of the nation’s food comes from, as well as major exports.

That fire season saw so much of Australia on fire. This project is going to impact that sort of scenario so much more by damaging our water supply.

Our food is going to run out. There are going to be harsher droughts. Our rivers are going to stop running, because they mainly rely on groundwater. And such a huge portion of land will be affected.

We’re already getting the effect of it being so hot that evaporation is occurring at night, as well as during the day.

That tipping point has already been reached along the Darling River, and we’re going to see it across more of the landscape.

It’s going to be devastatingly dry. It won’t be unusual to go and fry an egg out on the ground.

If the last bushfire season is anything to go by, it’s going to be huge and scary. There will be nowhere to go.

In terms of gas projects in the approval stages, Narrabri is not the biggest emitter, but it’s going to have the greatest impact for our everyday lives, on our food, our water and our ability to survive.

It’s really scary.

Pilliga Project screenshot detailing the proposed site of coal gas seam wells right across the continent

And lastly, at last Friday’s launch, it was explained that the documentary is open for free distribution and you stressed that you want people to share it widely.

The Narrabri gas project has been approved, and some of the gas seam wells have been drilled. So, at this stage in a fossil fuel development like this, what sort of chance is there of turning it around?

Shannan: They’ve got approval for 850 wells. But they have to get investment and make sure that they’re viable. And they’ve got to get the gas out.

The gas pipelines are still in approval stages. There are two of them that are yet to be decided upon. Those are points where we could have a major impact.

There are also the Kurri Kurri gas plans, which the local community in the Hunter is fighting against.

If you don’t have that plant, Narrabri gas could still go down to Newcastle, which is the aim at the moment. But if there’s no pipeline to move it, then it becomes a stranded asset and it’s financially painful, and they may not go through with it.

They do have backup plans, but if they can’t get the gas out, they can’t sell it.

So, if there are delays we’re off to a good start. It has already been delayed. Even though last year’s Mullaley gas and pipeline court case was unsuccessful, it did delay it for a long time.

As long as we keep delaying it, and the pipelines are hopefully stopped, then we’re off to a good start.

More broadly, across Australia, the whole climate movement is working on no gas and no fossil fuels. And if we win that social licence debate, then they’re much more likely not to go ahead.

And if we can vote differently at this year’s federal election, then we have a real fighting chance of stopping this.

Natalie: The gas wells haven’t been built in the Pilliga yet. So, that’s our golden opportunity. Once they’ve been built, it’s pretty much over. It will be impossible to stop it then.

But what happened in Bentley is we were able to stop gas because of grassroots organising. If they stopped it there before it happened, then the same thing can happen all over Australia.

https://youtu.be/cWXJzPYD9UY

Paul Gregoire is a Sydney-based journalist and writer. He has a focus on social justice issues and encroachments upon civil liberties. Prior to Sydney Criminal Lawyers®, he wrote for VICE and was the news editor at Sydney’s City Hub. Paul is the winner of the 2021 NSW Council of Civil Liberties Award For Excellence In Civil Liberties Journalism.

Feature Image: Wayne Lawler/Australian Wildlife Conservancy.

Editor of A Sense of Place Magazine John Stapleton has long been fascinated by the Pilliga and wrote a number of stories about it during his long journalistic career. Here are links to just two of them:

https://thejournalismofjohnstapleton.blogspot.com/2001/07/pilliga-lock-up-attacked-australian-6.html

The best known book ever written about the Pilliga: