The Big Grift: How the Top End of Town Rorted Jobkeeper. The Best of 2021.

By Luke Stacey with Michael West Media.

The most rampant era of welfare rorting in Australia’s history draws to a close at the end of the month when the JobKeeper scheme ends. Luke Stacey and Michael West investigate some of the big grifters and how they pulled it off … while we await a response from Business Council of Australia.

Mirvac racked up more than $20 billion in sales over the past six years and paid not a skerrick in income tax.

It also racked up profits through the pandemic, but that has not stopped the property juggernaut from helping itself to the government’s JobKeeper scheme too; gorging itself on a public subsidy that was intended only for companies that suffered a large fall in turnover.

Like dozens of other companies on the ASX – as demonstrated in the interim profit reporting season which draws to a close today – this profitable $10 billion company has grabbed the subsidy while having the cheek to pay large dividends to its shareholders ($305 million is the latest) and lavish salaries to its executives.

Others have paid part of their JobKeeper back; very few have paid back all of it. Yet, failing to demonstrate even a shred of integrity, Mirvac and its auditors PwC have grifted the lot, some $22 million in JobKeeper but zero paid back.

It’s even worse than it looks. Mirvac was the first to be outed for rorting Jobkeeper here last May when the scheme first kicked off. A young manager at one of the group’s retail centres told us she was asked to fill out a JobKeeper application form after she was fired.

“Mirvac chose to fire contracted employees across the entire business on April 21st 2020,” she told Michael West Media. “Mirvac exploited this Covid-19 crisis as a way to fire all staff employed on contracts.”

Mirvac is one of the more egregious examples, shaded by only a handful of rorters such as billionaire Solomon Lew and Premier Investments.

https://www.michaelwest.com.au/solomon-lew/embed/#?secret=nXX3LMYi1D

In the case of airlines and other industries left almost revenue-dead when the pandemic hit, JobKeeper has been a lifesaver, enabling companies to stay afloat and keep in contact with their workforces.

For others like Mirvac and Lendlease, whose income was barely affected, it’s a rort.

Should they pay it back? We put these questions to chair of the Business Council of Australia, Jennifer Westacott. Usually ubiquitous in her media appearances as the champion of big business, Westacott is missing in action when it comes to the hard questions about the accountability of her members.

The Global Financial Crisis might have entailed the public propping up the banks with guarantees but the pandemic is a bacchanalian rampage of corporate welfare never seen before. The concept that business can do without government support is dead.

Grand old department store Myer was flirting with obsolescence before the pandemic, that is until the government came along with JobKeeper and kept it alive. Not just that, Myer Holdings’ profit almost doubled and its share price almost tripled since its nadir of 10c a share last March as Covid fears swept around the world.

So JobKeeper was not only a rort for many, a lifeline for some but also a death-cheater for others, keeping inefficient, dying businesses alive for longer, impeding the invisible hand of the free market.

The rash of half-yearly financial accounts for ASX-listed companies shows only a small number are announcing full repayments of the JobKeeper subsidy despite a significant return to profits for many.

The New Daily conducted an extensive coverage of ASX JobKeeper recipients and the shortfall of wage subsidy repayments despite paying shareholder dividends and executive bonuses.

The government has kept its corporate welfare payments a secret but TND found (among the public disclosures from the companies themselves):

More than 60 ASX businesses disclosed receiving JobKeeper and other handouts

They recorded combined profits of $8.6bn over the past 18 months

They funnelled more than $3.6bn in dividends to investors since last April

They paid back just $72m

They paid out $20m in bonuses to executives.

Nine Entertainment is a classic case. Did people watch less TV and read less news during the pandemic? No, audiences were at home, more engaged than ever.

Last year’s lockdowns saw a spike in TV viewership and online activity with Nine Entertainment reporting a half-year profit of $181.9 million, up 79% on the year prior.

That didn’t stop them from putting out the begging bowl for $6.8 million in JobKeeper in the September round, of which $5.4m went to its majority-controlled Domain Group. It then received an extra $8.4 million in JobKeeper for the December quarter.

This corporate welfare is in addition to all the spectrum fees waived by the government in response to the pandemic, saving the group some $10 million, and then there’s the government-prompted deal with Google reportedly worth $30 million a year.

If you were to tote up the millions in government advertising received by Nine, along with the government’s pandemic subsidies, total corporate welfare attributable to Nine must be well north of $60 million.

You won’t read that in Nine’s Liberal Party-cheering publications, the supposedly free-market publications, Australian Financial Review, The Age and Sydney Morning Herald.

In order to salvage a modicum of decency from their feast on the public teat, Nine announced it would repay $2 million in JobKeeper received since the start of the scheme for their wholly-owned subsidiaries.

Yet the group still managed to pay $34.1 million in shareholder dividends last financial year and is poised to issue $85.2 million in dividends relating to the FY21 half-year.

Once eligible, now accountable

Michael West Media is not shining the light on profits to argue that, some companies at some point didn’t fall below the 30% revenue threshold (50% for businesses with a turnover of more than $1 billion) and were, therefore, ineligible for the scheme.

However, for businesses like Nine whose primary operations were not hindered by lockdowns – and only reported a 2% drop in revenue for the period – their failure to pay back JobKeeper in full is nothing more than a grift.

Not to put too fine a point on it, the public has been footing the bill for their employees and should be paid back. There is nothing in the legislation however to compel these grifters from paying back their handouts.

How do they get away with it?

Overall profits in annual or half-yearly accounts don’t specify a company’s month-by-month performance, where their income may have dropped below 30% in the months spanning the peak of the pandemic.

Each month, or alternatively every quarter, businesses are required to send a Business Activity Statement (BAS) to the ATO for them to determine how much GST each must pay. This tax legislation is what the government has used to pay the JobKeeper wage subsidy to employers. The ATO refers to a company’s BAS numbers for months during hard lockdowns against those same months in 2019 to determine how much JobKeeper the employer should get.

This may explain why property giants like Lendlease and Mirvac, which have paid $103 million and $305 million in dividends respectively, were able to rort it. Mirvac has received some $22 million in JobKeeper despite revenue of around $2 billion a year.

For example, Mirvac issues the tax office with a BAS for each entity it controls in Australia, with some potentially reporting the requisite drop in revenue for certain months last year.

This presents an apparent loophole in the JobKeeper scheme as it appears that businesses are able to break down their profits for each segment, disregarding their overall surplus. And even if a company returns to income that is near or exceeding pre-Covid levels, employers can stay on the scheme because according to the legislation:

“The decline in turnover test needs to be satisfied before an entity becomes eligible for the JobKeeper payment. Once this occurs there is no requirement to retest in later months”.

Examples include owner of Super Cheap Auto, Rebel Sport, and BCF, Super Retail Group, which has announced it would repay $1.7 million in JobKeeper covering their Macpac Retail division. The group received $6.5 million in total from the scheme, meaning they have elected to keep $4.8 million, half of which can be attributed to bonuses paid to executives last year.

This decision not to repay the full amount is despite a profit of $172.8 million for the FY21 period, up from $109.7 million at the end of last financial year. Super Retail also paid shareholders $44 million in dividends for the six months ending June 2020, and thanks to an increase in profits aided by the government subsidy, are set to deliver $74.5 million to shareholders in April 2021.

Another adopting this strategy is Collins Foods, which has committed to repaying $1.8 million it received from the government scheme, attributed to its Sizzler Restaurants brand. The group also owns the KFC and Taco Bell fast food franchises in Australia.

Unlike KFC and Taco Bell, Sizzler continued to operate at a loss following peak Covid restrictions last year, reporting the requisite 30% decline in revenue. Sustained poor performances prompted the board to close its remaining venues across Australia in October 2020.

Yet, with this move came a seemingly counterintuitive decision to repay its entire JobKeeper earnings. In its place, the group “topped up payments to the equivalent JobKeeper payment [Sizzler employees] would have received”. Essentially, Collins Foods matched the stimulus by tapping into its own reserves.

Their 2020 annual report shows revenue had increased by $80 million for the financial year across all brands. So despite poor performances from Sizzler operations, KFC and Taco Bell were still generating an overall profit for the group during the pandemic.

It’s for this reason that despite a positive turnover made by ASX groups such as these, they have still benefited from the JobKeeper scheme. And so long as the government does not mandate a repayment where necessary, it leaves the door open for the stimulus to contribute to shareholder dividends and bonuses at the board level.

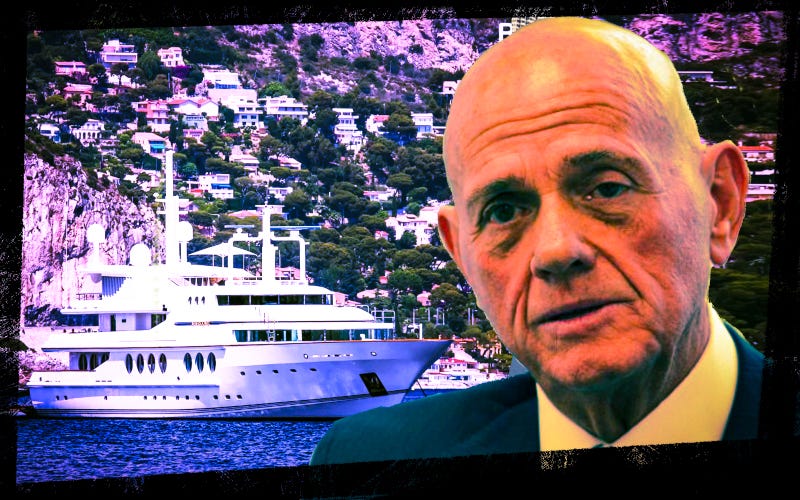

A notable example being retail billionaire Solomon Lew and his Premier Investments empire. Despite the pandemic, the group, which owns brands including Just Jeans and Smiggle, reported a 30% increase in profit, to $138 million, at the end of last financial year. A large part of this rise can be attributed to the $70 million they received in government wage subsidies, accounting for more than 50% of their profit for the year. The group did not disclose what percentage came from JobKeeper.

The high turnover resulted in approximately $57 million in dividends paid to shareholders, of which Lew himself received $24 million. The retail magnate also leveraged the pandemic to operate his 1200 retail stores rent-free.

Premier is yet to release its half-yearly accounts, nor have they issued any statement with the intention of repaying their various government wage subsidies.

A report last year from government advisory service Ownership Matters revealed some of the worst offenders of ASX companies paying bonuses to key management personnel while also receiving JobKeeper.

From these findings, Michael West Media reported that “Qube Holdings (QUB) gave its … key managerial personnel $2.78 million in the 2020 financial year.” Star Entertainment Group, owners of Sydney’s Star Casino, received $65 million in government subsidies and still managed to pay bonuses to executives of $1.39 million.

Other ASX entities shown to be rorting the subsidy include aforementioned Super Retail with executive bonuses exceeding $2 million, Lendlease, NIB Holdings and retail empire Accent Group.

Other frontrunners repaying the subsidy include Toyota, Domino’s Pizza, holiday property operator Ingenia Communities and retail furniture empires Adairs and Nick Scali. Even still, many of these returns have not been made in full.

Adairs announced $6.1 million in JobKeeper repayments from a possible $21.7 million after profits rose to $43.8 million for the December-half.

While the entire government package has not been repaid, Adairs argues the remaining wage subsidies have been retained as it covered employees who were not working or did not work sufficient hours to be remunerated.

This is still a heroic move in comparison to shipping group Qube Holdings which is in the throes of forcing almost 600 employees to pay back a portion of their JobKeeper payments. This despite Qube’s reported $940 million revenue in its FY21 half-yearly accounts.

Ingenia Communities will repay $1.7 million from a potential $5.1 million in JobKeeper. Their income for the FY21 interim period was $122 million.

It’s not clear how the group has determined the $1.7 million from its available total. Considering they will pay $16.3 million in dividends relating to this period, full repayment of the stimulus package is well within budget.

In a free enterprise economy, the government is not allowed to contribute to a company’s dividends. Considering dividends are dictated by an entity’s profits – enhanced by JobKeeper – this is exactly what has happened in many cases.

—————

Questions for Business Council of Australia chief Jennifer Westacott regarding JobKeeper for members:

How many of your members are receiving the JobKeeper subsidy?

What is Ms Westacott’s response to businesses who are receiving the subsidy while also paying dividends to shareholders and executive bonuses despite her condemnation in September last year?

Does Ms Westacott believe there is a shortcoming in the JobKeeper legislation whereby businesses that have now returned to making profits are not mandated to return the government subsidy?

Is Ms Westacott and the BCA at large embarrassed by the number of companies that continue to sponge from the JobKeeper subsidy when their half-yearly financial accounts show they no longer need it?

Ms Westacott’s responses will be appended if or when she responds.

Luke Stacey is a contributing researcher and editor for the Secret Rich List and Revolving Doors series on Michael West Media, Australia's leading investigative news site. He has built their corporate database of grandfathered companies on the Secret Rich List. Luke studied journalism at University of Technology, Sydney, has worked in the film industry and studied screenwriting at the New York Film Academy in New York. You can follow Luke on Twitter @lukestacey_

Feature Image by Alex Anstey.