Serious breaches were breaking through the fabric of things.

Back in London in the 1980s, I was using my new found status as a freelance journalist to pursue literary idols.

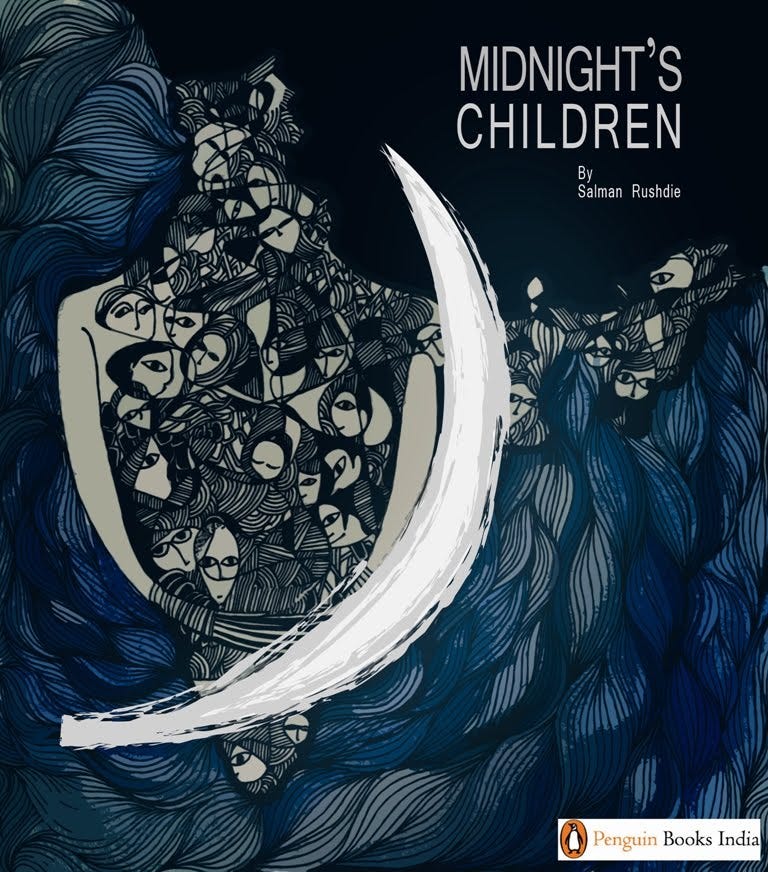

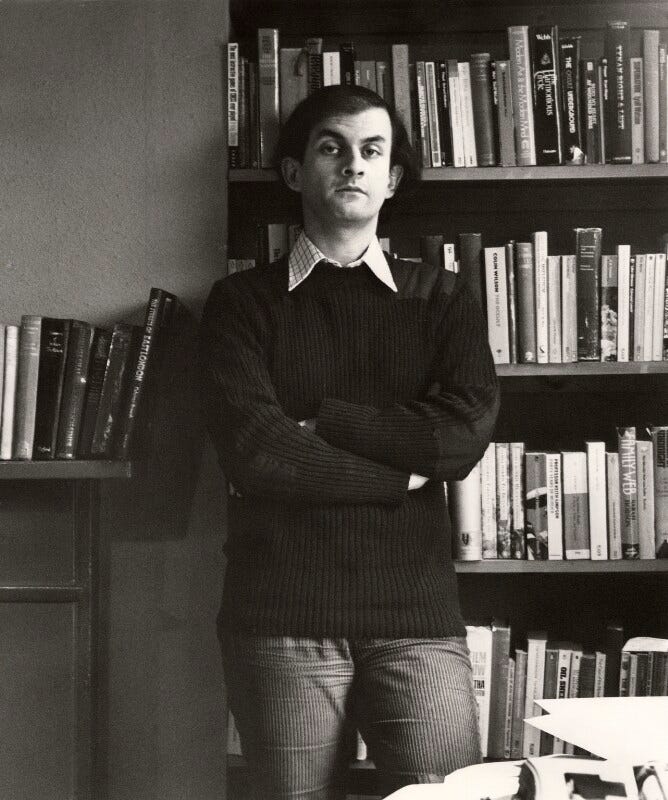

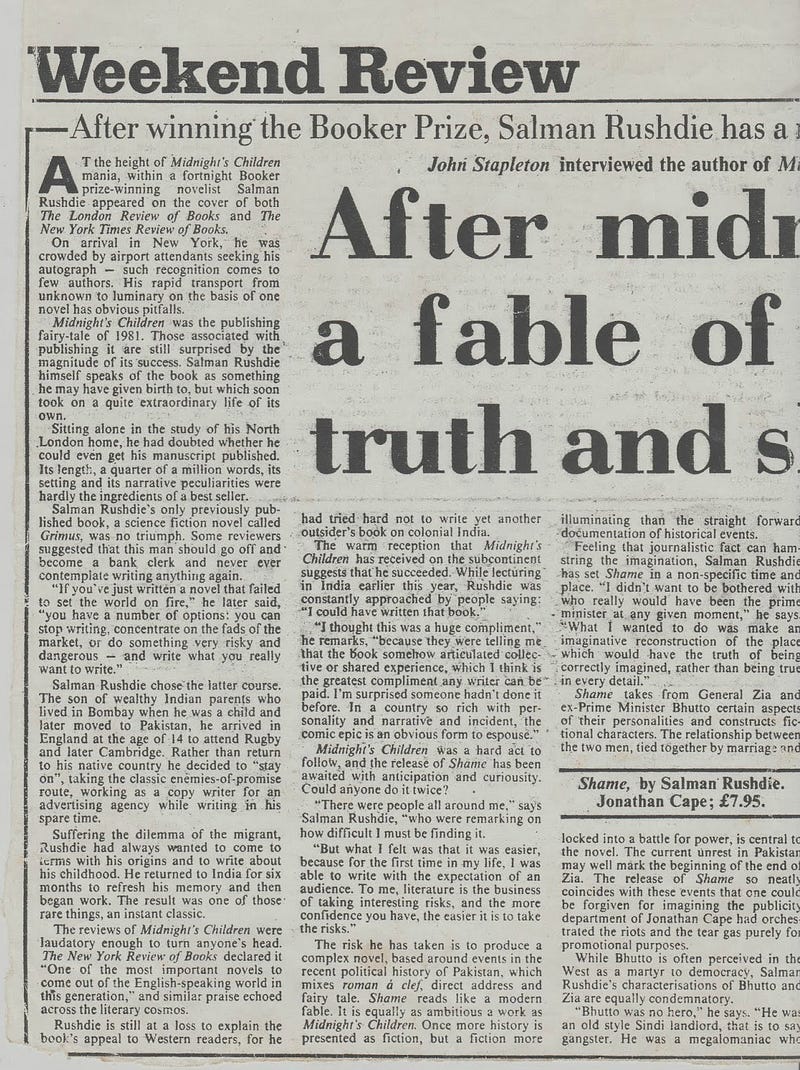

The interview with Salman Rushdie took place in the same room where he had written Midnight’s Children.

He was already world famous, having won Britain’s insanely prestigious Booker Prize.

These were the days before a voluminous The Satanic Verses scandalized the Islamic world and a fatwa was issued against him — a time when Rushdie’s fame was more or less contained within a bookish realm.

Back then the British treated Australians, colonials as we were, with something between amusement and contempt.

I doubt things have changed all that much.

Salman Rushdie was a special case.

It took a bit of effort to convince the PR woman that I should interview a man who had pole vaulted his way to literary stardom

Fortune favors the brave, often enough the foolhardy.

Brazen, I still found it relatively easy to inveigle my way into all sorts of situations. Lose my luggage; spend a lost weekend with the baggage handlers.

I was young, knew no fear, and was convinced fame and creative fulfillment lay ahead, on an ever upwards trajectory of success.

And yes, even Salman Rushdie had product to sell — Shame.

It was his first book after Midnight’s Children had set the world alight, and was being greeted with considerable anticipation.

Those were the days before numerous life pressures crowded out the days and I, like so many time-poor working journalists, would be obliged to interview people without having read a word of their work, heard their music or seen their paintings; barely having time to scan the press release in the taxi on the way to the job.

But these were different, pre-salaried days.

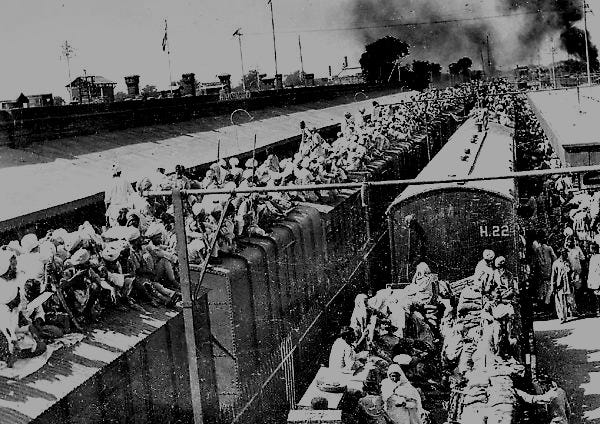

And so it was that I found myself outside Salman Rushdie’s London house, frantically trying, before the allotted interview hour, to finish reading Shame, a black, sprawling work set in Pakistan.

The landscapes are full of camel drivers and stunted trees, shrouded women made eerie in dust storms.

None of the characters are admirable, the plot confusing and the politics dark. It promptly disappeared from the public imagination.

The Multiple Voices of Midnight’s Children

I particularly loved Midnight’s Children, as had millions of other readers. I read it in Bombay, or Mumbai as it became known in 1995, where the book was set.

I even went to the obsessive length of visiting some of the locations in the book, including the site of a Jain temple in a sprawling, jumbled area of Mumbai possessed of a wonderful feeling of fading wealth.

Midnight’s Children, as so many critics observed, resonated with the chaos and multiple story lines of India.

The first paragraph sets the tone, and perhaps explains the world’s obsession:

I was born in the city of Bombay. . .once upon a time. No, that won’t do, there’s no getting away from the date: I was born in Doctor Narlikar’s Nursing home on August 15th, 1947. And the time? The time matters, too. Well then: at night. No it’s important to be more. . . On the stroke of midnight, as a matter of fact. Clock-hands joined palms in respectful greeting as I came. Oh, spell it out, spell it out: at the precise instant of India’s arrival at independence, I stumbled forth into the world. There were gasps and outside the window fireworks and crowds. A few seconds later, my father broke his big toe; but his accident was a mere trifle when set beside what had befallen me in that benighted moment, because thanks to the occult tyrannies of those blandly saluting clocks I had been mysteriously handcuffed to history, my destinies indissolubly chained to those of my country. For the next three decades, there was to be no escape. Soothsayers had prophesied me, newspapers celebrated my arrival, politicos ratified my authenticity. I was left entirely without a say in the matter. I, Saleem Sinai, later variously called Snotnose, Stainface, Baldy, Sniffer, Buddha and even Piece-of-the Moon, had become heavily embroiled in Fate — at the best of times a dangerous sort of involvement. And I couldn’t even wipe my own nose at the time.

Rushdie At Home

The London house where Rushdie lived at the time was a large hushed home which even then must have cost a substantial amount of money.

Rushdie came from a wealthy family. Struggling to survive was not part of his life experience.

In contrast I was living in squats at the time, and the casualness of the money struck me. My own life had been riddled with bohemian friends, and I was impressed by this world of casual wealth, influence and success.

A maid opened the door. It soon became apparent that all four floors of the house were occupied by the Rushdie family; an astonishing thing in the London I was most familiar with.

His wife of the time appeared briefly before disappearing into the bowels of the house. I was escorted up to Rushdie’s study.

In those days, before my shorthand and personal hieroglyphics became good enough to keep up with most conversations, I used a tape recorder, which I duly set up.

We were amiable together more or less from the beginning.

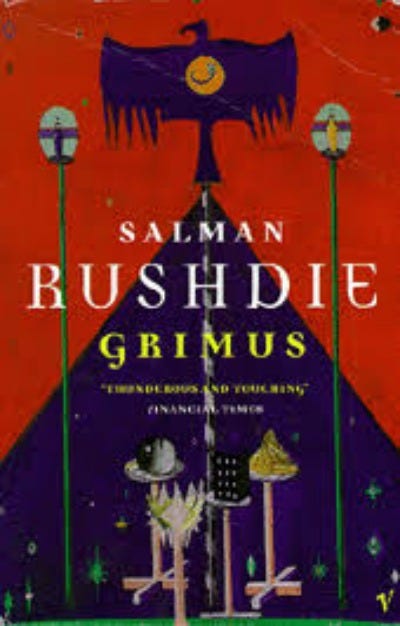

We had something in common: we both liked science fiction.

Surprisingly, given all the plaudits rained upon his later work, his first book Grimus, published in 1975, had belonged to the much disparaged genre.

Well connected, even then, he had managed to attract a major publisher.

But that was as far as it got.

As one reviewer suggested, Grimus “nosedived into oblivion amidst almost universal critical derision.”

Another suggested he should go off and become a bank clerk, and never contemplate writing anything ever again.

The Phenomenal Crowds of India

There I was, a literary journeyman, sitting in the very study where one of the most famous books of the era had been written.

I had been to India, met many Indians.

But like other Western travelers, most of the Indians I had met were on the streets, shopkeepers, rickshaw drivers, hotel staff.

It took a while to adjust to this level of wealth, this superior grace, Rushdie’s perfect English, extravagant courtesy, high order of education.

Rushdie went out of his way to put me at ease.

I asked him, I don’t know why, in an intimate rather than reverential way, if he was surprised by the phenomenal success of Midnight’s Children.

He spoke disarmingly of the fame that had been thrust upon him.

He showed me the desk where he had written the Booker Prize winner and replied: “If you had written a book like that, just sitting here, not really talking to anybody, without any orthodox plot, with multiple voices inside it, the voices of India, could you have possible imagined it would be a success?”

“No,” I replied.

And then the author pointed out a framed black and white photograph of a house featured in Midnight’s Children, the rambling Indian house where he had grown up.

And the question everybody was asking: could he do it again? Could literary lightning really strike twice.

There were people all around me who were reminding me how difficult I must be finding it. But what I felt was that it was easier, because for the first time in my life, I was able to write with the expectation of an audience.

To me, literature is the business of taking interesting risks, and the more confidence you have, the easier it is to take risks.

So Much Was To Follow

The interview went well.

Afterwards, Rushdie saw me graciously to the door.

I walked back down the road into my own contrasting life.

After that intimate hour with one of the world’s most celebrated writers, I always followed Rushdie’s career with interest; the wall of secrecy and security that surrounded him after the death threats stemming from Satanic Verses, the changed wives, the run of books.

The Moor’s Last Sigh, Shalimar the Clown, most recently The Golden House.

Nobody ever dared edit Salman Rushdie after the stratospheric success of Midnight’s Children. Not that I’ve read them all, but I must admit there were moments in his subsequent voluminous, expansive, unrestrained books when I found myself skimming across paragraphs and sections, with that sneaking, could I be so arrogant thought: “If I had been the editor…”

His was the very opposite of writing for newspapers, with their tight deadlines and clipped word counts.

Personally, I would have been dead in some self-destructive orgy if I had been allowed such indulgence, if I had not been forced by circumstance to get up every day and go to work, to write about the real world.

The public relations person from Jonathan Cape said Rushdie had rang after our encounter and told her it was the best interview he had ever done.

I couldn’t have been more chuffed.

Not all interviews went as well.

Douglas Adams, author of the comedy science fiction series The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, rang up after my flood of questions ceased and loudly told the PR woman: “That’s it. No more interviews. I don’t care who’s scheduled.”

I had a similar effect on the rock star Marilyn at the Savoy Hotel in London, when he said loudly to his on-hand publicist words to the same effect, making sure I heard.

Author Fay Weldon decided she didn’t like me the moment we sat down at her kitchen, while at the same time taking a great liking to my intense German artist friend Kristoff, who I had brought along for the ride. We think these moments are significant. They’re not. We think they will last forever. They don’t.

Singer Elvis Costello, another god of the era, gave me withering look well beyond disdain when I asked him what the song Every Day I Write the Book meant; as if it wasn’t self explanatory.

Sometimes, facing yet another famous person, you just run out of questions.

Adapted for Medium from the upcoming memoir Hunting the Famous.

John Stapleton worked as a news reporter on The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian for more than 20 years. A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.