Research reveals 111 times Australian Quolls reportedly Chewed on Human Corpses

By David Eric Peacock.

Warning: this article contains graphic descriptions of human disfigurement.

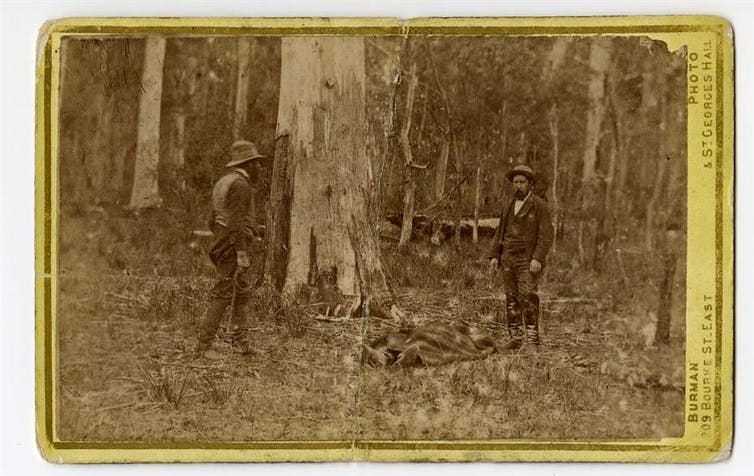

In 1878, the body of Sergeant Michael Kennedy lay in the bush in Victoria’s Wombat Ranges. He’d been shot by the notorious Ned Kelly gang – but the bush would add its own gruesome ending.

According to the man who later stumbled across his body, “one ear was gone. I imagined it had been gnawed away by native cats (quolls). The body was very much decomposed”.

This report is not isolated. My recent research has found 111 accounts between 1831 and 1916 where the scavenging of a corpse was attributed partly or entirely to quolls.

These grisly reports reveal a fascinating picture – not just of quolls, but of life in Australia in the 1800s.

A captivating carnivore

Quolls, historically known as native cats, are carnivorous marsupials. Four species are native to Australia: the spotted-tailed quoll, and the western, eastern and northern quoll.

Quoll populations in Australia have been declining for more than a century. Tasmania’s remaining eastern quoll population, for example, fell more than half in the decade to 2009 and numbers have not recovered since.

Quolls are known to scavenge. But I wanted to know more about their scavenging of human corpses. I hoped this would yield further insights into the animal’s diet and feeding behaviour.

Delving into a gruesome history

Of the 111 historical accounts I found of quolls scavenging on a human corpse, six involved definitive evidence – either eyewitness accounts of the behaviour, or tracks and scats at the scene.

In 1862, a police officer saw seven quolls scavenging a corpse near Sale in Victoria. Upon being disturbed they ran into a dead tree. The policeman “burnt them and the tree to the ground” – revealing the widespread antipathy towards quolls at the time.

Tragically, in two cases quolls were seen feeding on infant corpses: at Araluen in New South Wales in 1895, and Sydney’s Middle Harbour in 1897.

And a sorry account tells of a man lost in the forest at Winchelsea in Victoria. Found near death, he said quolls and other animals “had eaten his fingers and his toes. They had bitten his face and torn his nose away”. He died soon after.

In 105 accounts I identified, quolls were not caught in the act of disfigurement, but were assumed to be the culprits.

In 1831, for example, Captain Bartholomew Thomas died in the Tasmanian bush after an Aboriginal spear attack during the Black War. When his body was found it was missing half the throat. A member of the search party speculated it had been eaten by crows or “native cats”.

In a modern context, it may seem a huge leap to attribute so many corpse disfigurements to quolls. And of course, correlation does not equal causation.

But during the period, quolls were a major problem. They were recorded invading homes and other buildings, and in one account from South Australia, someone’s bed.

In 1856 at Glencoe in South Australia, 550 quolls were killed in one day after the animals reportedly gnawed on boots and stock whips.

And quolls were, and remain, abundant in a few parts of Tasmania, threatening rabbits, chickens, poultry and captive birds.

So in this context, assuming a quoll was responsible for scavenging a human corpse was only natural.

What we can learn

In the 1800s and early 1900s, quolls were found across Australia. But the accounts I uncovered were limited to Tasmania, and a wide coastal-inland band from the Queensland/NSW border to just east of the South Australia/Victoria border.

Those areas had significant human populations – and newspapers to report their observations – which may explain the pattern. But at the time, the eastern quoll reportedly reached plague proportions in some places, and may have been desperate for food.

The victims spanned all reaches of society: a former convict, swagmen, farm workers and labourers, Chinese settlers and Aboriginal people. They died from a range of causes including murder, suicide, old age and misadventure.

Some 85% of the reported human victims of quoll scavenging were male. This is consistent with social attitudes during the 19th and early 20th centuries, when the outdoors was an overwhelmingly male domain.

Quolls are most abundant in late spring and summer. However, 41% of human scavenging accounts were reported in winter, and only 16% in both spring and summer.

This likely demonstrates quolls are hungriest in winter, as you might expect. But it also reflects the challenge of human survival at the time. There were minimal social supports, and human frailty or misadventure could easily lead to death from exposure.

Most accounts reported facial damage – to the eyes, ears, nose or tongue. Fingers and toes were reported in just three accounts.

Clothing worn by the person at their death, such as gloves, may help explain this. It may also reflect a bias on examining the face when identifying a corpse.

But it could also suggest quolls preferred some human body parts over others. In Tasmania, for example, quolls typically start on soft animal parts where they are able to tear open the skin.

Bringing back the quolls

I uncovered few corpse disfigurement accounts after 1900. This is consistent with a massive decline in quoll numbers by this time, reportedly after constant persecution by humans, and disease.

Australia’s four quoll species are now struggling to survive. They’re variously listed as endangered or vulnerable, due to perils such as habitat loss, introduced cats and foxes, poisonous cane toads, climate change and car strikes.

Quolls are beautiful and special animals. I want to spread their story far and wide in the hope efforts to protect them will be expanded.

In some cases, fox and cat control has allowed quolls to return to places they’ve been absent from for many years. But more conservation measures are needed.

Let’s hope quolls never again chew on a human corpse. But, restored to healthy numbers, perhaps they can resume their role in the bush as tough and wily predators.

David Eric Peacock, Adjunct Fellow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.