Real World Drawing: Dobell Biennial

By Ari Chand

Why do drawers draw?

Drawing is historically connected to creative practice, but also truth and accuracy. It helps materialise story and culture, perhaps because it’s often the fastest way to get an idea down on paper. But drawing can also be slow, meditative and reflective. When the artist is in the flow state, a drawing can take hours and hours to resolve itself.

The 2020 Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial is an insightful window into the active compulsion of drawers. With the theme of Real Worlds, this wonderful array of work turns our minds back to representational forms of drawing and the way in which the medium envelops our connection to self, place, and country.

The works provide pause to consider the visual narrative and what the future of drawing might look like given new technologies — but less government support — at the tertiary level.

Real versus abstract

Sir William Dobell won the Archibald Prize for portraiture three times but his day job as a draughtsman is often referred to. Perhaps this is an attempt to legitimise his skills. Since the controversy of his 1943 Archibald prize — an image of fellow artist Joshua Smith derided by some vocal critics as caricature — his work has always made us question what is drawing today?

The Dobell Biennial, which ran from 1993—2012 alongside the Archibald as a prize worth A$30,000 before being reinvented as a curated exhibition, continues the conversation. The Dobell Drawing Prize, now hosted by the National Art School, was won last year by Justine Varga for a work entitled Photogenic Drawing (2018).

Real Worlds exhibits a tight selection showcasing the ideologies and technical skills of eight artists.

Curator Anne Ryan points provides a litmus test of drawing now. The eight artists featured are Martin Bell, Matt Coyle, Nathan Hawkes, Danie Mellor, Peter Mungkuri, Becc Ország, Jack Stahel and Helen Wright.

Read more: Great time to try: learning to draw

Traditional boundaries

On the whole, they use tried and true methods.

The work of Ország requires us to evaluate the role of observation and composition. Her work expresses our longing for a Utopian pre-technological society.

Stahel’s drawings and made things to draw show how boundaries can be crossed between scientific thought and visual beauty. https://www.youtube.com/embed/3lLFx987G2c?wmode=transparent&start=0 The drawings ‘reflect our capacity to imagine something better and different’ says Dobell Biennial curator Anne Ryan.

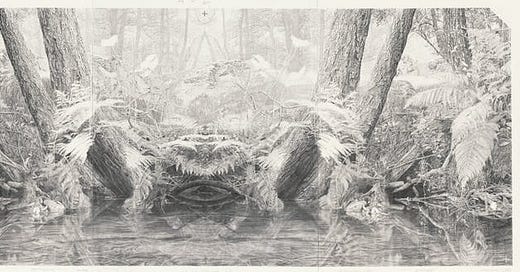

Mellor’s work connect us to ecology, history and Dreaming narratives while Bell’s impressively sized, interwoven type, line drawing and nostalgic drawn-on-paper tapestry recalls the 80s.

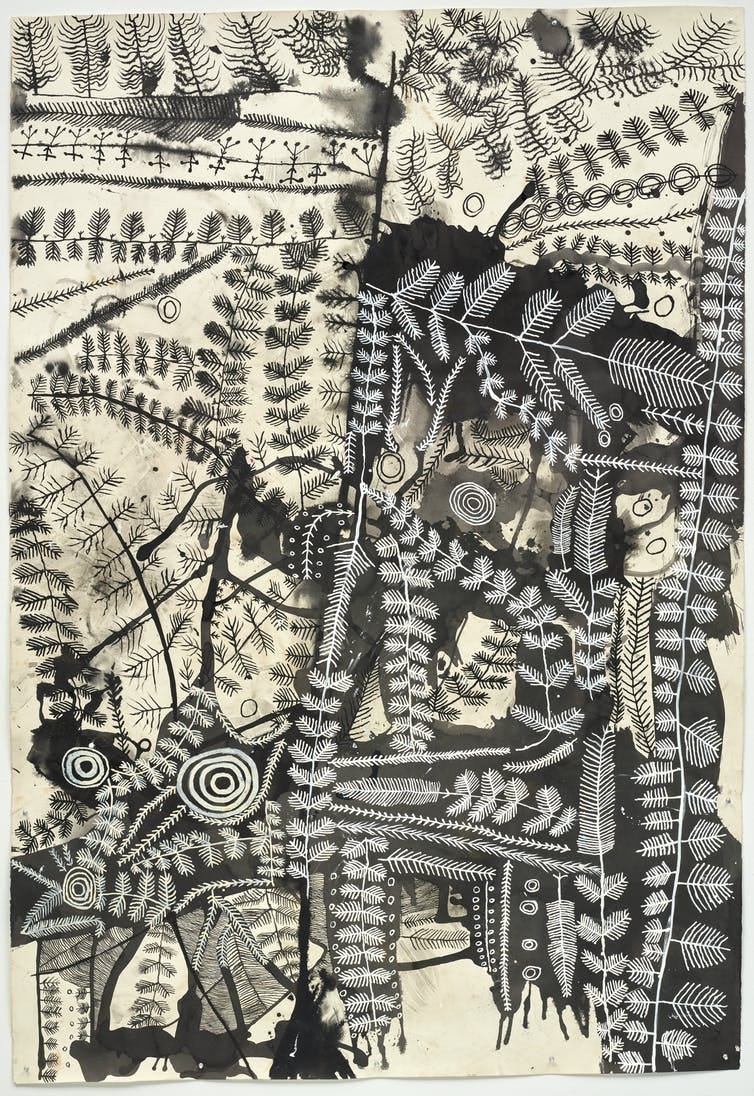

Mungkuri’s large layerings of Country in ink captivate and pull the viewer into a mesmerising cartography. Coyle wants you to dream alongside him, while Hawkes provides a splash of colour. Finally, Wright’s drawings tap into human fears of excess consumption.

The sheer scale of the works is striking and the time involved is impressive. Each artist shows us the deeply cognitive nature of their practice.

Learning to draw and think

The skill and technique of drawing has been diminished in schools and university curricula.

People aren’t sitting around drawing all day like they once did, (slowly thinking), and new funding models for the arts suggest they won’t anytime soon.

Read more: The government's funding changes are meddling with the purpose of universities

The newly formed Drawing Education Network seeks to understand the potential of drawing across all forms of education and to counter this shortsightedness.

As noted at a recent event, the dynamic of drawing within universities has dramatically shifted over the last 20–50 years. We might be losing a generation of learning for “job ready” visualisation skills — despite operating in a visual era. https://www.youtube.com/embed/7RmcJHNGgtc?wmode=transparent&start=0 Keynote Presentation ‘un-thinking Drawing and un-drawing thinking’ with Stuart Medley and discussion with Alan Male.

Yet drawing continues to be widely utilised across journalism and reportage, education and knowledge transference, persuasive advertising and marketing, strategic planning, and narrative fictions and entertainments.

The future of drawing lies in its ability to persist throughout time, notes University of Newcastle creative industries head Paul Egglestone:

Drawing continues seemingly unfazed — even energised — responding to and feeding off copious new ways to make images — electronically and mechanically — on film, video and computers. Images are being made today we can legitimately call drawing that would not have been possible or even imaginable at one time.

Read more: Why is teaching kids to draw not a more important part of the curriculum?

Feature Image: Danie Mellor’s A Time of World’s Making (2019) detail. Danie Mellor/AGNSW

Following the Art Gallery of NSW exhibition, Real Worlds: Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial 2020 will tour regionally to Lismore Regional Gallery (27 February–25 April 2021) and Museum of Art and Culture Lake Macquarie, yapang (8 May–18 July 2021).

Ari Chand, Lecturer in Visual Communication Design and Creative Industries, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.