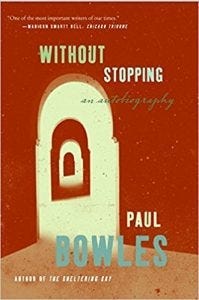

Paul Bowles and the Sheltering Sky

ONE BELONGS TO THE WHOLE WORLD, not just one part of it, Paul Bowles once told an interviewer. Gifted annually with a round-the-world free ticket courtesy of my father’s job as a Captain on Australia’s national carrier Qantas, for a time I made the most of it. It was more interesting to be impoverished, for I never had much money, anywhere else but Australia.

Morocco was always associated with turning points, and held a fascination to generations of writers from William Burroughs to Gertrude Stein and a parade of many others, Tennessee Williams, Jean Genet, Mark Twain.

I had been there on more than half a dozen occasions over the years; since acquiring a fascination for Spain in the days when Franco was in power. It was not very difficult to hop a ferry across the Mediterranean to Tangiers.

Those were the days, the 1970s, when you could buy a book called Europe On Five Dollars A Day.

At one point, in a rare foray into heterosexuality, I hung out with an American hippy. After a trip from Tangiers on the famous Marrakesh Express she complained she was only getting sex twice a day and it just wasn’t enough. Personally, I thought it was not just enough, it was exhausting. We said our farewells and she headed even further south with another group of bohemian travellers. Determined to have a good time, bonking.

A Place of Transitions

Years later I celebrated my son’s first birthday on the balcony of a Tangiers hotel with his once again pregnant mother growling monstrously in the background. For whatever reason Morocco was a place for transitions.

The English treated Morocco much as they treated the south coast of Spain, the Costa del Concrete — that is as a theme park in which to play out their own predilections.

British gay men loved the rough, hard, handsome Moroccans for the same reason they flocked to places like Thailand — the local rough trade was an attractive, cheap and usually less dangerous contrast to the pudgy potatoes in their own towns and cities. You paid. They played. Simple as that.

Morocco was a place of infinite romance; of mystery and magic beyond the veil.

It was this side of Morocco that Paul Bowles wrote about so well.

I loved his writing long before I ever met him; adored The Sheltering Sky long before it was made into a movie. I had gone to the obsessional length of reading one of his novels, The Spider’s House, in the hotel in Fez where it was set.

“The likeness of those who choose other patrons than Allah is as the likeness of the spider when she taketh unto herself a house, and lo! the frailest of all houses is the spider’s house, if they but knew.”

Koran.

The Sheltering Sky

Bowles was, if not exactly a mentor in any practical sense, an artistic hero, someone who had dedicated his life to perfecting an art form.

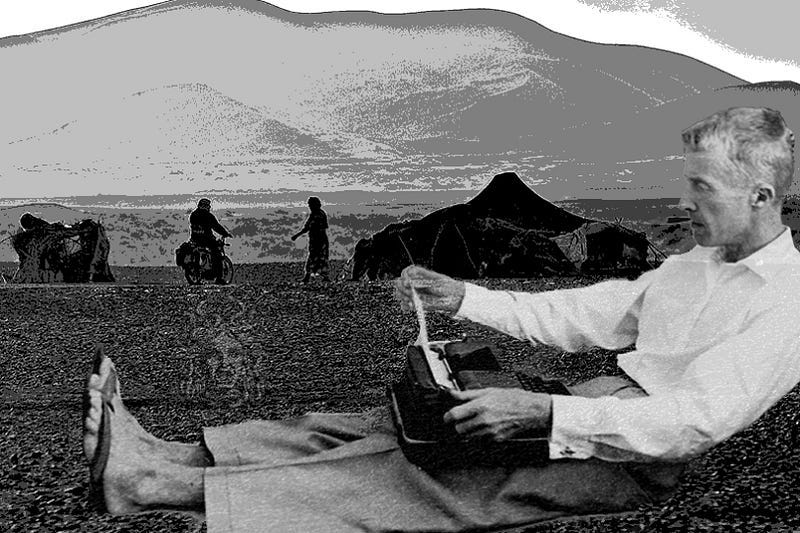

I read The Sheltering Sky several times; once while driving across Morocco smoking ludicrous amounts of hash, the desert mountains dissolving in visual tableaus, merging with the words on the page.

Sometimes I would insist we stop the car and then go for a walk, perch on the top of one of those beautifully colored Moroccan desert outcrops with joint in hand, and just read.

It was natural, when I was in Tangiers, to track Bowles down.

Martin, the boyfriend of the time, had never travelled until our lives collided in what even then was a remote outpost of human consciousness, Adelaide in South Australia.

Apart from anything else, unable to sit still, having never stopped stopped in the one place for long, I liked having someone to share writing and travel adventures with. For a time we were both enormously happy with each other. I was convinced we were at the beginning of a great adventure. That the world was ours, anything was possible.

Frederico Garcia Lorca

In Madrid I had tracked down and interviewed Iain Gibson, who had just written the first volume of a superb biography of the Spanish poet Garcia Lorca.

Following the interview we stayed for a hugely enjoyable dinner with his family.

The one thing I had already discovered about journalism, it allowed you not just to pursue your own interests, but to meet your heroes. And the dribbling amounts of money, well it all helped.

At the time, long before mass travel turned much of the world into a theme park trampled by suburbanite hordes, I was filled with the romance of travel; the hope of a great life, the intoxication of literature. Everything seemed possible.

Before arriving in Morocco we had travelled the thirty miles from Granada to visit Lorca’s childhood home; a white house in the center of the village of Fuente Vaqueros, the Fountain of the Cattlemen, in the heart of Andalusian Spain. It became a beautifully maintained small museum dedicated to the memory of the poet.

Set on plains and open farmland beside a small village; the atmosphere inside the house bordered on the sacred.

Most travelers end up visiting a ridiculous number of museums, cathedrals, churches, mosques, temples and points of historical interest. Few of these sites stay lodged in the traveler’s memories for long.

Lorca’s childhood home stayed lodged in my memory — forever.

Garcia Lorca, one of the most lyrical and admirable of poets, remembered his younger days as a time of pure, unambiguous emotion, free from the destructive powers of politics and time.

As Leslie Stainton wrote in the book Lorca: A Dream of Life: “In childhood, his parents had loved him unconditionally. Each morning before dawn, his father had come into the room where Federico and his brother and sister slept, and gently kissed their faces… Shortly afterward, Lorca’s mother would stride into the room and, with a brisk ‘May the grace of God enter,’ open the shuttered windows, cross herself, and lead her children in prayer.”

From Lorca’s childhood home, we returned to Granada and then made our way south to Tangiers.

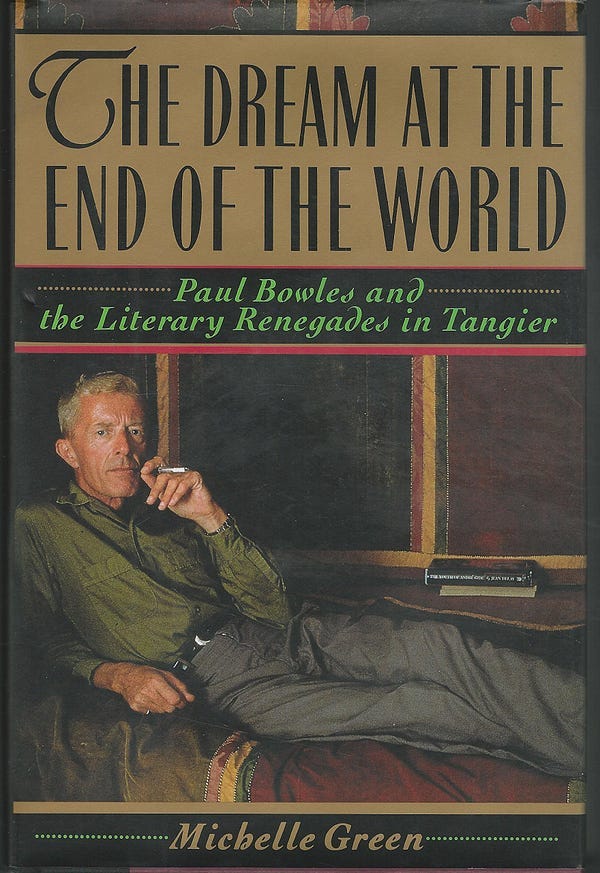

The Dream at the End of the World

Exultant from the beauties and adventures we had experienced in Spain, we approached Morocco with an upbeat sense of wonder.

On a corner of one the port’s many narrow, winding streets there was a bookshop which sold English language books, and on the advice of one of the ever-present Tangier boys who stuck to us like glue from the minute we got off the ferry, that’s where we went.

Just as in India, when in Tangiers there was only one way to deal with the throngs of pestering multilingual touts, pickpockets and neighborhood “guides”.

And that was to pick one, who usually promptly managed to convince you to include their friend. And then the pair protected their prize as if you were made of gold; fighting off all comers and ensuring you were neither robbed nor mobbed. They were loyal to the end because they knew you would tip them well if you were happy with their services. From my experience, the worst any of them ever did was occasionally drag us off to their uncle’s carpet shop.

The sight of besieged backpackers carrying their loads through haranguing mobs and crowded streets still strikes me as a ridiculous one. They think they are saving money but they aren’t. A judiciously aimed couple of dollars can turn arrival in a Third World city from a nightmare to a pleasure just like that.

The particular two school-aged friends who adopted Martin and I that year led us self-importantly through the narrow streets of Tangiers to the book shop. They were guides for two foreigners, while many of their contemporaries were thronging the docks each day hoping in vain to find a rich tourist to help feed their families.

These two had done everything from produce a limited edition of a rare Tennessee Williams work, written and published in Morocco, to keeping us entertained with demonstrations of just how many languages in which they could say “hello good morning what would you like madam”.

The two of them laughed a lot on our various explorations of Tangiers and its surrounds; and proved very entertaining company.

In a port city like Tangiers, the world comes to its doors. These boys, street wise but nevertheless from good families and attending school most of the time, were living lives light years away from the sheltered, isolated childhoods of Australian suburbia.

On our request that we would like to meet Paul Bowles the bookshop owner replied: “Bowles is a friend of mine. I will check for you.”

He explained that visitors were sometimes welcome, but only at particular times in the afternoon.

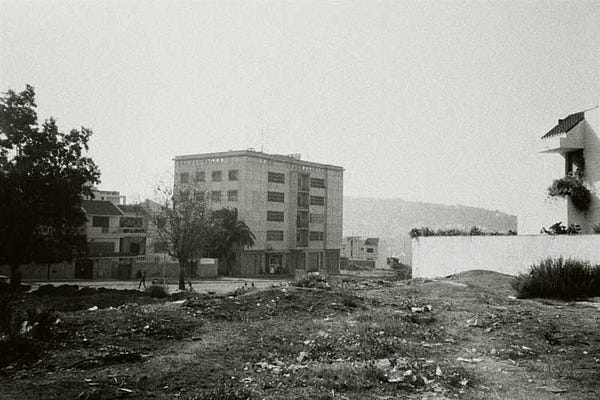

Eventually the same two boys who had kept such a proprietorial eye on us led us to Bowles apartment. As we passed out of the main quarter of Tangiers and towards the scruffier outskirts of the back of the town, I started to grow skeptical.

A wind that was dry and warm

Nobody wrote like Paul Bowles:

A wind that was dry and warm, coming up the street out of the blackness before him, met him head on. He sniffed at the fragments of mystery in it, and again he felt an unaccustomed exaltation. Even though the street became constantly less urban, it seemed reluctant to give up; huts continued to line it on both sides. Beyond a certain point there were no more lights, and the dwellings themselves lay in darkness. The wind, straight from the south, blew across the barren mountains that were invisible ahead of him, over the vast flat sabkha to the edges of the town, raising curtains of dust that climbed to the crest of the hill and lost themselves in the air above the harbor. He stood still. The last possible suburb had been strung on the street’s thread. The Sheltering Sky.

And that was the way it felt that day.

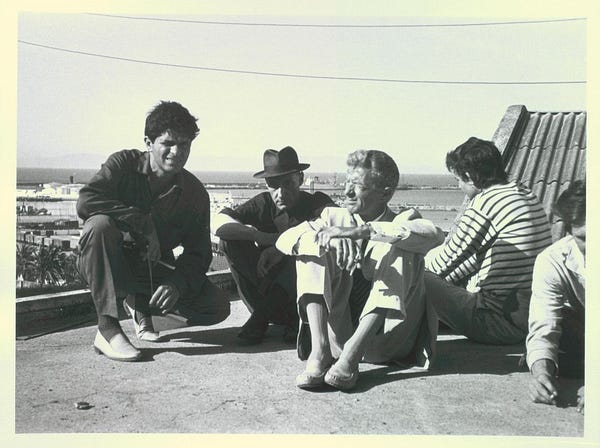

But sure enough, we arrived at a rundown apartment block where Bowles’ driver, lazily running a polishing cloth across an old sedan, confirmed that indeed the writer was at home.

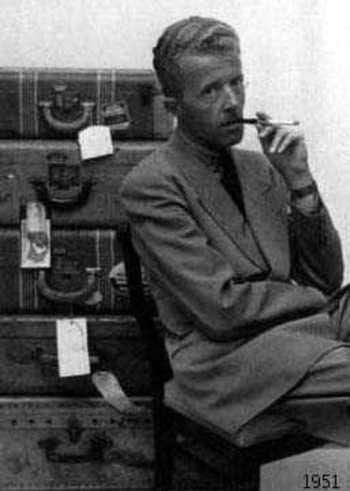

For someone so legendary, for someone who had written one of the most celebrated novels of the 20th Century, I was expecting some sumptuous Moroccan fantasy of a house, as extravagantly beautiful as his writing.

Could this possibly be right? This dreary looking place?

We went up in a creaking lift

We went up in a creaking lift, and were greeted at the door.

It was Bowles’ salon time, four to six, the only time of the day when visitors he did not know personally were welcome.

Bowles never had to go anywhere. The world came to him.

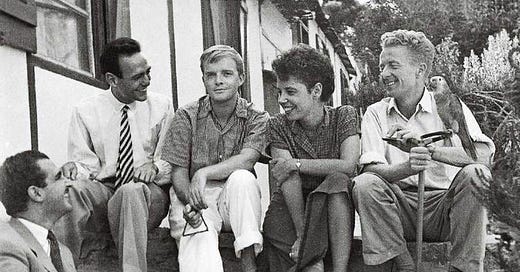

A small group of loyal acquaintances came to chat and smoke kif each afternooning, visiting ex-pats, the Moroccans he had transcribed or translated into English, a young acolyte from Brazil, good looking of course, an erudite Spanish woman Bowles had known for decades. I was completely fascinated.

Fleetingly I would have cheerfully dumped Martin. This wasn’t his destiny, it was mine. He wasn’t the one with the great love of Paul’s books; with the utter fascination for the milieu of which Paul had been a part. Martin just liked the fact that we were meeting someone famous and appreciated the precocious way I went about these things.

Bowles had met, for God’s sake had known and been friends with another idol of youth, William Burroughs, whose years as a chronic heroin addict in Tangiers were detailed in his writings.

Bowles had known Tennessee Williams and the kindness of strangers. He had met Jean Cocteau, Andre Gide, Christopher Isherwood, Stephen Spender, was friendly with Gore Vidal.

Jane Bowles, the author of Two Serious Ladies, really had been his friend and wife. He was a direct heir of the great tradition of English literature which spilled down the decades to this very point.

I was from Australia and in the years before the internet and the so-called Information Revolution the rivers of the world’s literary traditions barely washed up on the shores of the Land Down Under.

Patrick White won the Nobel Prize in 1973. I had adored his books, Voss and The Solid Mandala and The Tree of Man, but they weren’t the world at large, they were a transfiguring lyricism of a microcosm, a place at the end of the Earth. Half a century on, and White’s books are rarely read, having virtually disappeared from the contemporary literary canon.

None of the members of Australia’s prickly and often incestuous literary scene had hung out with William Burroughs; they weren’t part of the image charged tradition I then adored: the ticket that exploded, the dusky smell of rotting oranges, fish boys ejaculating on silver streams, scaffolds where the bodies of naked, dying men jerked spasmodically in the desert heat.

I didn’t know any Australian writers who could do hallucinatory decay so devastatingly well.

Paul Bowles was part of history and there wasn’t anywhere on Earth I more wanted to be than sitting in his lounge room.

We sat around in a circle, in that rundown apartment.

I Caught a Glimpse

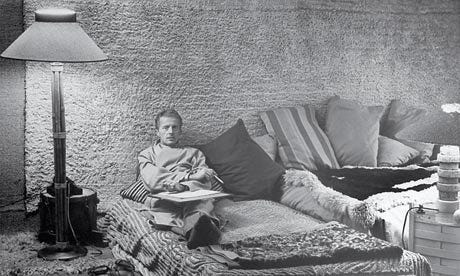

Bowles might have been world famous but he lived simply.

I caught a glimpse of his single bed in the sunroom alcove. There were medicine bottles lined up on the bedside table. Even then his health was beginning to fail.

He was frail, ethereal almost, as if the world was too vivid a place for him, which was why he sheltered in this apartment, away from it all. Which was why he could write a book like The Sheltering Sky.

There was a circle of us, some woman visiting from Britain he clearly knew well, the attentive Moroccan men he had sponsored for years, and in particular his protégé, a Moroccan author he translated into English. Bowles smoked kif, a mild form of marijuana mixed with tobacco, more or less constantly.

The pipe went round and round the room in a familiar ceremony.

Years later, when my son Sam was one-year-old, I returned to that apartment with Sam perched in a backpack, the old boyfriend Martin no longer in tow.

I had left my son’s very pregnant and not very happy mother back at the hotel.

It wasn’t the allotted salon hour for visitors, but after knowing Bowles over such a long span of time I felt familiar enough to just knock on his door.

I wanted him to meet my son, of whom I was enormously proud.

Not having seen Bowles for some years at that point, for a moment Paul confused me with another Australian journalist he was expecting. Not only was he aging, he had such a steady stream of visitors the brief confusion wasn’t any wonder. Then he located me in his memory and invited me in.

As my one-year-old, having literally just started to walk, toddled around the famous writer’s apartment we got to talking once again in that familiar, confessional way we had.

I tried to tell Paul everything that had happened in the years since we’d last met, as if he was a great uncle: how I had got a job in mainstream journalism, left the boyfriend he had met and was now a father for the first time.

I’m not sure it made much sense to him; in his increasingly whimsical state.

“Will you write another novel?” I asked.

“You have to have something to say,” he replied.

As if life had already happened and these were the unexpected days, when he had outlived everybody he had ever known and there really was not much more to be said.

“I’m like a tourist site,” Bowles complained once. “People feel compelled, entitled, to come and have a look.”

He didn’t mind, he said, as long as it was during his salon hours, but thank God the 1960s were over. Brash Americans from the country he had long turned his back on would arrive at his door, barely knowing who he was, dump their backpacks at his feet and drawl: “Mind if I crash here maaan?”

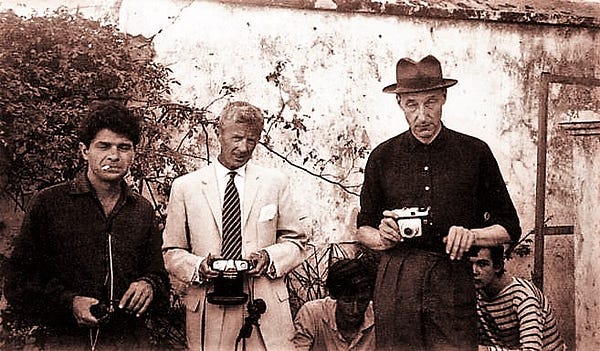

Bowles was, in the purest sense, a man who had chosen the creative life and the creative struggle above all else. His intelligence, his musicality, his warmth, set him apart as an intellectual in a time of the beatnik, as a truly old world man of letters. It was impossible to imagine him indulging in the chemical excesses of William Burroughs who’s own Tangiers exploits were perhaps more famous. He looked like a shot of rum would kill him. He did not drink. I was, in the end, though he meant so much to me, no doubt just another tourist visiting a particularly interesting site. Bowles had already been famous for so many decades, since the 1940s and the publication of The Sheltering Sky, that he was well accustomed to evotes. He was the Sacred Muse.

I had been living in London, doing odd jobs in between bouts of literary journalism. The whole future lay ahead, a glorious place. I had somehow got it into my head that it was my destiny to meet famous people and interview them.

The last time I saw Bowles he was sick and noticeably more frail than before.

The line of various medications beside his bed had grown even longer. We talked as if everything had to be fitted into a single afternoon; of far off Australia and the creative muse; and I told him my dreams in a way I had never told anybody else; the bewildered pact a young child made to the creative life. The fear that greatness was already out of reach. The hope that one day I would write something as beautiful as The Sheltering Sky. And of the fascination I had for Morocco, the exotic country he had chosen as his home.

Paul, from an entirely different world, talked of the work he did for the American national library collecting and recording ethnic Moroccan music, his pride in encouraging, helping to get published and translating local authors into English; of his absolute determination never to return to America, the country of his birth. This was his life now, he said, the crowded Tangier streets, the dust, the donkeys, the street urchins running through the alleys. And the magic that lay behind the country’s landscapes. Just as he did in his books, he talked about the dark, superstitious feel of the place, the hypnotic music of the desert nights, the allure of the villages, the utter strangeness of it all, the dangerous, mysterious, intoxicating Morocco which lay just out of sight, unnoticed by the average tourist.

He showed off a bookcase of foreign translations, and then complained that his books didn’t make much money. Publishers were always ripping him off.

The famous Bertolucci movie The Sheltering Sky had changed nothing. There were no signs of increased affluence.

He still had the same loyal driver, the same battered old car. And he still lived in the same old apartment in a not very upmarket area of Tangiers.

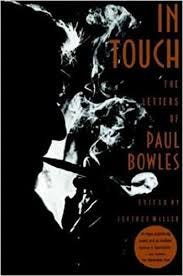

Bowles wasn’t writing then. Instead, probably sensing that his time was drawing to a close, he had been compiling a collection of correspondence spanning decades.

There were papers and letters everywhere, in scrappy piles. It must have been unbearable, picking through all those memories. He looked so frail that last time I saw him, sitting on a cushion on the floor of his apartment, smoking his kif, lost in thought as he sorted through old letters from long dead friends. No wonder he was whimsical..

It felt lonely, it felt old. It felt as if the good times had passed. It was hot outside, but inside he still had a gas fire burning.

The bottles of medications beside his single bed had multiplied.

We talked over the correspondence, letters from Jane Bowles, letters from an array of the famous and infamous. Already in the process of becoming relics of a bygone era when people wrote letters.

As if he was a father figure to report back to, I tried to tell him everything that had happened in my life since I last saw him; how I had gone back to Australia, got a job on one of the country’s leading newspapers, broken up with the person he had met, become a parent.

Afterwards we walked down the hill together to collect his mail, a daily ritual of his in that far off era when people actually went to post offices. Bowles was shockingly thin, and we walked only slowly through the dusty streets. As if all was coming to a close.

The book of letters he had been working on when I last saw him was published in 1995 and was called In Touch: The Letters of Paul Bowles.

Publisher’s Weekly described the collection thus:

Expatriate American novelist, story writer and composer Bowles, who has lived in Morocco for nearly a half century, is a prolific letter writer, as attested to by his expansive, conversational correspondences with the likes of Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Gore Vidal and Virgil Thomson. A vast humming tableau of the avant-garde, these 400-plus letters extending from 1928 to 1991, vividly evoke Bowles’s frenetic activity in the Paris of the 1930s and ’40s, where he met Jean Cocteau, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and painter Pavel Tchelitchew. Peppered with firsthand impressions of Tennessee Williams, Leonard Bernstein, Kurt Schwitters, Aaron Copland and many others, the volume, edited by his biographer, also contains Bowles’s sharp lyrical travel observations from Mexico to Ceylon, as well as his reflections on the unconscious processes that guide his writing of fiction.”

That Final Day in The Great World

That final day, after we collected his correspondence from the Tangiers central post office, an impressive swag of interesting looking letters, we said our farewells.

I went back out into The Great World.

I was working as a journalist for the national newspaper The Australian when Paul Bowles died in 1999, at the age of 88.

Fanciful notions of writing great books had been banished by the daily churn of journalism. Murdoch journalism. Flat, unresponsive, vested in the power interests of the day, a slave not to fashion but to the financial interests of a man who had done more to destroy the roots and integrity of the profession than any other media mogul in history.

I wrote a story about Bowles for the literary pages of the national newspaper where I worked but the piece was never published. What would a general news reporter, a humble hack on the highways of print, know about such things? How could I possibly have known one of the all-time greats?

But I had known him, by simple dint of knocking on his door.

I felt sad as if a close friend had died.

I remained out in The Great World; and in much the same way as happened to Bowles, if not with quite such illustrious company, many friends, indeed the majority of old friends, died.

The future was indeed Another Country.

The most remarkable thing about books is that they are a code passed down the generations. We, the commoner, can learn from, delight in and gossip about all the greats, from the present and from the past.

Just as so many others had been forced to do, from W.B. Yeats to Eugene Delacroix, from unsung geniuses of carpentry and farming to history’s most celebrated artists to a million others, I was forced to find a talent and a vocation. A place in the world. The mastery of artistry. And for that, Paul Bowles helped me in an unforgettable way, there under The Sheltering Sky.

The spirit was uncloaked. From madness and chaos, a destiny had been set.

+++++++++++++++++

This piece is an extract from the forthcoming book Hunting the Famous.

John Stapleton worked as an Australian journalist for much of his life. A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.