Overlooked for Decades, this Shy Little Wallaby has a White Moustache and Shares its Name with a Pub Meal.

By Elliott Dooley and Matt Hayward, University of Newcastle

For many people, the term “wallaby” may describe a single species, or rather just a small kangaroo. So you may be surprised to learn there are actually more than 50 known species of wallaby in Australia.

The parma wallaby (Macropus parma) is one of Australia’s smallest. It’s no larger than a house cat, with a body length up to 55 centimetres and a tail about the same length again. It has thick, brownish-grey fur, and a defining white moustache.

But this is about as much as can be said for its appearance, as even its moustache is common to many other wallaby species, such as the yellow-footed rock-wallaby.

Here, we aim to defend the voiceless. The parma wallaby’s failure to charm with either its looks or charisma has condemned it to obscurity by the general public and wildlife researchers alike, potentially dooming it to extinction.

The parma’s resurrection

So overlooked is the parma wallaby that for more than 30 years, it was presumed extinct until 1966, when a feral population was discovered on Kawau Island, New Zealand.

The species was introduced there a century earlier by former Prime Minister of New Zealand, Sir George Grey, who’s zoological interests led to Kawau becoming home to a menagerie of exotic animals.

This sudden rediscovery resurrected the parma from the pages of natural history books, prompting a reintroduction program to re-establish the Kawau Island population in Australia. This occurred on two occasions, once on Pulbah Island in Lake Macquarie, and near Robertson, NSW. But both attempts were considered abject failures, with all reintroduced, marked individuals found dead, mostly due to predation by dogs and foxes.

Despite this unsuccessful program, the sudden spotlight on the species led to its rediscovery on the mainland in 1972 near Gosford, NSW. Soon after, a state-wide parma survey was conducted.

An elusive species

But since then, its ecology has largely gone unstudied and, once again, the parma has faded to obscurity.

The IUCN Red List — the pre-eminent assessment of the conservation status of the world’s biodiversity — has relied on a guestimate of population size, placing it at under 10,000 individuals.

Despite little monitoring the species is still considered only “near threatened” on the Red List, but events like the Black Summer bushfires may have significantly reduced its population.

Read more: Meet the broad-toothed rat: a chubby-cheeked and inquisitive Australian rodent that needs our help

As a result of its cryptic nature and very recent rediscovery in the wild, there is scarce known about the ecology of the parma wallaby. We don’t even know the exact origins of its name.

We do know its preferred habitat is moist eucalyptus forest with thick, shrubby understory. It shelters there during the day, often with nearby grassy areas as, at night, they typically feed on grass and herbs. They’re also found in rainforest margins and drier eucalypt forest, but to a lesser extent.

The parma wallaby is under threat

We also know the parma wallaby’s range is in decline and has been since European colonisation.

The species once occurred from southern Queensland to the Bega area in the southeast of NSW. Now, its range is confined to the coast and ranges of central and northern NSW. It’s patchily distributed throughout cool, high-altitude forests along the Great Dividing Range.

It weighs around 5 kilograms, placing it in the critical weight range category. This means it’s vulnerable to feral predators, such as dogs, cats and foxes.

Read more: One cat, one year, 110 native animals: lock up your pet, it's a killing machine

Another major threat facing parma wallabies is habitat destruction from catastrophic bushfires.

The 2019-2020 Black Summer bushfires killed, injured or displaced an estimated three billion animals. Over half (55%) of the parma’s key habitat was severely burned. Coupled with the loss of those that would have perished in the flames, the species is now considered vulnerable in NSW.

Saving the parma

The recent bushfire Royal Commission raised the issue that Australia doesn’t have a comprehensive, central source of information about its native flora and fauna. This is especially urgent, given seemingly “drab” species like the parma wallaby that have gone unnoticed for too long.

All species rely on interactions with a plethora of other species to survive in a complex system from which humans are not exempt. But with so little known about these interconnected relationships, we don’t know what the broader impacts to the ecosystem would be if one species disappeared.

Imagine a Jenga tower where each species is a wooden block. You can never really be certain which block you remove will cause the tower to collapse. Australia has an appalling extinction record, and we can’t afford to be playing Jenga with our biodiversity — whether it’s a boring bird, an ugly fish or just another wallaby.

Our ongoing research aims to help fill this conservation gap. We focus on a range of conservation actions the parma wallaby needs immediately.

These include carrying out field surveys to gauge the extent of their survival, and identifying the places that need refuge vegetation recovery. Refuge patches of bushland are important because they provide parma wallabies escape routes and places to hide, helping protect them from predation.

But you can help, too

Given the breadth of catastrophic fires is expected to increase under climate change, we can all help threatened species like the parma wallaby bounce back.

Come bushfire season, you can reduce the fire risk around your home by clearing anything that could fuel a fire — long grass, weeds and leaves on the ground and in guttering.

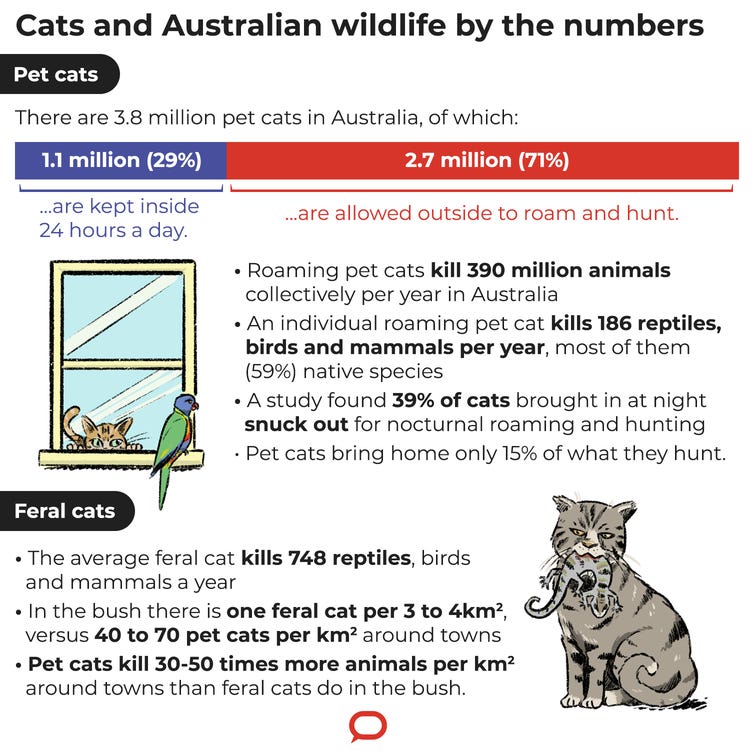

The parma wallaby, like many other little mammals, is vulnerable to introduced predators, especially cats. By keeping your cat indoors, you could be sparing the lives of 186 animals per year.

You can urge your politicians to value Australia’s unique and precious biodiversity. They are the ones who will ultimately determine whether our threatened species survive or go extinct.

Finally, you can volunteer. There are many volunteer-based conservation projects all over Australia, run by government agencies, charities, and universities.

With the ongoing pandemic travel restrictions, there’s no better time to experience the rich biodiversity this country has to offer, and discover less celebrated, but still fascinating, species like the parma wallaby.

Elliott Dooley, PhD Candidate, University of Newcastle and Matt Hayward, Professor of Conservation Science, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.