Masons in Australia. Part One: Early Settlement and The Rum Rebellion

TOTT NEWS

It appears that in the 18th century, whenever a revolution occurred, the Freemasons were not far behind. This includes the early settlement days of Australia and the infamous 'Rum Rebellion'.

Since the eighteenth century, the Rosicrucian-led Freemasonry guild have sought to establish a new civilisation that is fundamentally opposed to the ‘old order’.

Freemasonry was not only a primary instrument in the growth of ‘scientific knowledge’, but also in opening the public mind to the ‘enlightened’ view of man and nature.

Given the significance of Freemasonry as an ‘enlightening impulse’ during this time, these omissions provide a good reason to rethink the history of that revolutionary age.

While Australian school kids are taught of the ‘evils’ of white people and the fictitious Frontier Wars narrative of the settlement period, the real story details a struggle between the state and free men.

A struggle that began and ended in similar fashions on other continents in the same period.

Why have eminent intellectual historians excluded Freemasonry from their analyses?

THE SPIRIT OF MASONIC REVOLUTON

Influential Freemasons helped to further the 18th century Enlightenment period with mass promoted ideas such as ‘equality’, ‘freedom’ and ‘tolerance’. Concepts that would underpin a season of revolution.

AMERICA

The events of the American Revolution and subsequent formation of the American colonies into an independent republic were carried out in accordance with universal Masonic principles, by Masons.

Probably the best accounting of Masonic membership among the signers of the Declaration of Independence is provided in the book Masonic Membership of the Founding Fathers, by Ronald E. Heaton, published by the Masonic Service Association at Silver Spring, Maryland.

According to this well researched and documented work, proof of Masonic membership can be found for almost a dozen signers of the Declaration of Independence. They are:

Benjamin Franklin, of the Tun Tavern Lodge at Philadelphia.

John Hancock, of St. Andrew’s Lodge in Boston.

Joseph Hewes, a Masonic from Unanimity Lodge No. 7, Edenton, North Carolina.

William Hooper, of Hanover Lodge, Masonborough, North Carolina.

Robert Treat Paine, present at Grand Lodge at Roxbury, Massachusetts, in June 1759.

Richard Stockton, charter Master of St. John’s Lodge, Princeton, Massachusetts in 1765.

George Walton, of Solomon’s Lodge No. 1, Savannah, Georgia.

William Whipple, of St. John’s Lodge, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Masons could also be found in leading positions on the battlefield, including General Joseph Warren, Grand Master of the Ancient’s Provincial Grand Lodge of Massachusetts. Warren lost his life at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775 and his body was thrown into an unmarked grave.

While he had led the American troops during that battle, his lodge brother, Dr. John Jeffries directed the British troops on the opposite side of the fence (to ultimately fail).

Think about that for a moment.

In many ways, the revolutionary ideals were espoused by the Masonic fraternity long before the American colonies began to complain about the injustices of British taxation.

Those expressed in the Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence, and the writings of Thomas Paine, were ideals that had come to fruition over a century before, where men sat as equals, governed themselves by a Constitution, and elected their own leaders.

In many ways, the ‘self-governing’ Masonic lodges of the previous centuries had been learning laboratories for the concept of ‘self-government’.

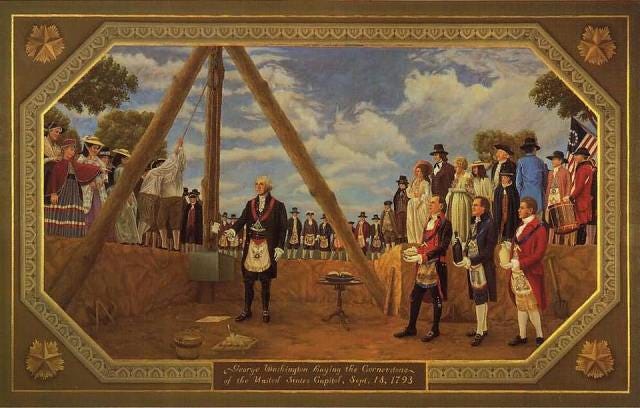

On September 18, 1793, President George Washington, dressed in his Masonic apron, levelled the cornerstone of the United States Capitol with the traditional Masonic ceremony.

Historian Stephen Bullock in his book, Revolutionary Brotherhood, carefully notes the historic and symbolic significance of that ceremony.

The Masonic brethren, dressed in their fraternal regalia, had assembled in grand procession, and were formed for that occasion as representative of Freemasonry’s ‘new found place of honour’.

At that moment, the occasion of the laying of the new Republic’s foundations, Freemasons assumed the mantles “high priests” of that “first temple dedicated to the sovereignty of the people,” and they “helped form the symbolic foundations of what the Great Seal called ‘the new order for the ages’.”

FRANCE

The French Revolution was a turning point in modern European history that began in 1789 and ended with Napoleon Bonaparte’s ascension at the end of the 1890s.

During this time, French citizens have destroyed and reshaped their country’s political landscape, destroying secular institutions such as absolute monarchy and feudalism.

The cause of the troubles was widespread dissatisfaction with the French monarchy and the poor economic policies of King Louis XVI, who was executed by guillotine with with his wife Marie-Antoinette.

It was the original revolution of the period, and gave birth to many more (including America).

In fact, Benjamin Franklin (with his masonic connections) raised money for American Revolution between 1776 to 1785 in France. Everything is explicitly tied together.

And, once again, we can find that Freemasonry played an important role in revolutionary France.

In official brochures, symbols such as Eye Seeing All and Plumb’s Rule, are used to represent the illumination and justice that the French Revolution is supposed to bring.

The Enlightenment itself was brought to the fore by writers such as the Masonic Voltaire, who influenced the origins of the Revolution, as well as Thomas Paine, which he wrote with his support.

Maximilien Robespierre, hero of the cult of the Supreme Being (who presided over the terrors of the revolution), was a capricious Freemason.

This should come as no shock, as Masonic lodges were first warranted in France in 1725. Prior to the revolutionary period, there were 1,250 lodges in France with an estimated 40,000 members.

Many books have been published over the years that detail how the French Revolution was nothing more than a Masonic conspiracy.

The most notable was written by a French refugee priest, a Jésuite named Augustin Barruel.

In his memoirs on the history of the Jacobins, Barruel argued that the French Revolution was the culmination of a “subterranean war” waged by secret societies to destroy the church and the monarchy.

Barruel has accused Voltaire’s philosophy of fomenting Christian hatred and Adam Weishaupt, the founder of the Illuminati, of encouraging atheism.

Barruel’s thesis was frequently followed later, particularly during the Third French Republic, by Catholic authors who used it to oppose both republicanism and Freemasonry, and by Freemasons to strengthen their pro-republican position and positive image in the eyes of the Republican government.

Among the Freemasons active during the revolutionary period were:

Mirabeau, Chauderlos of Laclos.

Roget of Lall, the author of the national anthem “La Marseille.”

Louis-Philippe.

Marquis of Lafayette.

Jean-Paul Marat.

In the French Egypt that followed their conquest of Egypt in 1799, around 1810, the “Egyptian” rites and freemasonry appeared among the French forces stationed in Italy, before spreading to France in 1814.

At the end, because of the role of the Freemasons in the French Revolution, freemasonry has become inseparably linked to revolutionary ideals — and the proof is in the pudding.

However, few are aware that Masonic attempts against the Empire also spread to Australia.

AUSTRALIA’S EARLIEST MASONS

In 1770, just six years before the American Revolution, James Cook’s HMS Endeavour made the first European exploration of the east coast of Australia.

Cook named the land “New South Wales” and took possession in the name of King George III.

However, little did Cook know that the Masonic brotherhood was also along for the ride.

Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks, the naturalist who sailed into Botany Bay with James Cook in 1770, is the most notable. He is thought to have been the first Freemason to set foot in the continent, becoming a mason prior.

At some date prior to 1769, he had become a member of the Somerset House Lodge which, led by Thomas Dunckerley, subsequently amalgamated with The Old Horn Lodge.

Sir Joseph Banks Daylight Lodge No. 9828, which meets at Horncastle in Lincolnshire, is named him.

Interestingly, in 1778, Joseph Banks became President of the Royal Society of London.

A position he would hold for over four decades!

Yes, this was one of the main men on board HMS Endeavour with James Cook, seen pictured in this famous account of discovery from the Australian National Library:

This is the man who helped arrange the ill-fated expedition of Captain William Bligh, which led to the famous mutiny on the Bounty. Keep this in mind as we move to the next section of this piece.

Thomas Lucas

Another notable Mason was Thomas Lucas, a Private in the Marine Corps who arrived with the First Fleet. Thomas aged 56 years died on 29 August 1815 and was buried at St David’s Hobart.

At his funeral, the Masonic Lodge performed their ceremonies over a “brother mason” at the graveside.

According to the Fellowship of First Fleeters, Rev. Robert Knopwood was the Officiating Minister who entered the following details in his diary for that day, 1st September 1815:

“At 3.00pm I buried Mr. Lucas from Browns River. He has been a marine that came out when the settlement at Port Jackson was formed, then became a settler and went to Norfolk Island.

There he remained till the island was evacuated; most of the settlers came to this colony. He was a Mason, and buried by the Brothers in masonic form.“

We will speak more on the influence of Norfolk Island is just a little bit.

Matthew Flinders

Matthew Flinders, who arrived in 1795, was involved in several voyages of discovery between 1791 and 1803, with the most famous of those being the circumnavigation of Australia and an earlier expedition when he and George Bass confirmed that Van Diemen’s Land was an island.

Flinders was a proud and prominent Mason, who would eventually coin Australia’s masonic name.

It seems like that, much the same as other revolutions detailed, Freemasons had infiltrated many levels of the Great Britain system, as can be seen by these explorers of the Empire.

However, the top of the kingdom was still a Liberal Democracy, and the activities of these individuals would still remain hidden for years to come in the face of a very cautious Great Britain.

AUSTRALIAN SETTLEMENT

THE PRE-LODGE ERA

NSW takes pride of place for the establishment of the first Masonic Lodge.

However, by the time New South Wales was founded in 1788, freemasonry was well established in Britain. It was popular in the army and in the East India Company, both of which influenced early New South Wales.

Contrary to popular belief, Freemasonry had tentative beginnings in Australia.

In the first 20 years from 1788, authorities in charge of the penal colony were very suspicious of unauthorised meetings, particularly those held in private.

At the precise time that white settlement of Australia was beginning, secret ‘combinations’ throughout Britain and mainland Europe were being proscribed and, where located, raided and members charged.

Secret Committees, authorised by the House of Commons, were attempting to track any and all conspiracies and all agitators.

Their caution was justified, as the Australian penal settlements were not only the destination of petty criminals, but also of political prisoners who were transported from Ireland, England, Scotland, Canada, the West Indies and other British colonies.

Not only were high-ranking Masonic members of the Empire lurking, but the population was now growing to include practising members (who opposed the state) or those who would be converted.

This is the context in which the secret society members were transported here to strike their first blows, with Masonic connections also known to have helped finance convict transportation to Australia.

As we will explore, some of these would grow to become wealthy and influential entrepreneurs.

This was happening a century before the first official lodge opened in Australia.

In 1938, Karl Cramp and George Mackaness provided one of the first published accounts of Freemasonry in Australia, which has now become the default history of the earliest years.

According to the authors:

“Craft Freemasonry, as we now know it, was not regularly practised in Australia until the year 1816.

Prior to that date, however, we have evidence of at least three occasions where Masonic arts were either proposed or practised in Sydney.”

Instead of focusing on Australia’s first lodges, what needs to be investigated is the point where members of the professional military class began to shape the early settlement period with these new populations.

In their new location, Australia’s early Freemasons began achieving sufficient substance that has remained potent well into the modern age, now causing very deep and lasting control at all social levels.

How did these Freemasons manage to ‘shape’ the early settlement?

Through taking control of resources and much of the emerging trade under the authorities.

THE SPREAD THROUGH SOCIETY

While much of late-18th century tumult centred on reform efforts around ‘universal rights’ and ‘the brotherhood of man’, there were lots of suspicion.

Freemasonry was directly involved in the earliest attempts to provide shape to the southern penal settlement, first in its struggle to survive and get then to beyond being a place of detention.

Some were clearly what we would call ‘conspirators’.

Freemasonry, both because of its idealism and its day-to-day practice, was directly involved in trade.

For example, the tavern The Freemasons’ Arms (now Woolpack Hotel) was built at Parramatta between 1797 and 1800.

This was one of the first pubs to ever be opened in Australia and still holds Sydney’s longest continuing liquor license.

As we will explore soon, monopoly over the alcohol trade would ultimately lead to violent rebellion in the penal colony.

This would be a key avenue of the Masons.

In addition, the New South Wales Corps (sometimes called The Rum Corps) was formed in England in 1789 as a permanent regiment of the British Army to relieve the New South Wales Marine Corps, who had accompanied the First Fleet to Australia, in fortifying the Colony of New South Wales.

Many of the officers and men in the New South Wales Corps were Freemasons. Captain Anthony Kemp, an early paymaster of the Corps, was just one example. More on Kemp in a little bit.

Cramp and Mackaness note that in the records of the Grand Lodge of Ireland is reference to a meeting of that Grand Lodge on 6 July 1797 where a petition was received from George Kerr, Peter Farrell and George Black, praying for the issue of a warrant to be held in the New South Wales Corps.

The authors speculate that there may have been a Lodge in the Corps and that Kerr, Farrell, and Black

were its three principal officers.

Through control of the Corps, Freemasons were able to influence early Australia largely by stealth. Alcohol and military control was vital in gaining further leverage without detection.

The reason for so much sneaking during this period?

The young colony had a wall of anti-Conservative, anti-Mason men, to get around first.

EALY GOVERNORS

Men Against the Masons: Arthur > Hunter > King > Bligh

Arthur Phillip, the first Governor, is believed not to have been a brother, despite some officers and some of the rank-and-file troopers aboard the First Fleet being so.

He is the man that raised the Union Jack at Sydney Cove on 26 January, 1788.

When Phillip was appointed as governor-designate of the colony and began to plan the expedition, he requested that the convicts that were being sent be trained.

However, only twelve carpenters and a few men who knew anything about agriculture were sent, consolidating trade knowledge early on. This raised alarms.

Phillip, during his time, established a civil administration, with courts of law, that applied to everyone living in the settlement.

Phillip was a battle-worn veteran, who was nearing the end of his time as an official. He soon handed over the reigns of Governor to a keen John Hunter, who he likely shared suspicions of infiltration with.

In 1796, the Governor was John Hunter. He issued the liquor licenses at the time and would have a much better understanding of the trade activities that were going on.

Research suggests that John Hunter was opposed to Freemasonry, which reportedly did not sit well with the likes of Kerr, Farrell, Black and others.

Freemasonry was associated with Conservatism due to the nature of the American Revolution, and thus, any decent serving member of the British Empire (not compromised) would be on high alert.

Hunter was one of these men, who ensured the activities of Freemasons remained hidden in society.

Almost exactly midway between 1770, the year of Cook’s arrival off Eastern Australia, and 1788, when the First Fleet discharged its bemused passengers, the Gordon Riots in London resulted in huge destruction.

A decade later, concerns in Britain about threats to the established order led to the Unlawful Societies Act of 1799, which governed the activities of Freemasonry in Britain until repeal in 1967.

As a result, tensions were high, and any type of group meeting without consent was now considered to be something that would draw attention. Of course, this did not sit well with the Masons in Australia.

The eyes of the state were now watching every corner, and soon, tensions would boil over.

PHILLIP KING VS THE MASONS

Phillip King, a naval man, was very wary of freemasonry. He would take over from Hunter as Governor.

When King became Governor in 1800, with Britain at war with revolutionary France, he became understandably jittery. Several hundred Irish rebels were transported after the 1798 rebellion, including some of the leaders who escaped execution, and they brought Masonic ideas with them.

King’s resistance to this brotherhood, perhaps passed down from former Governors, caused him to strike.

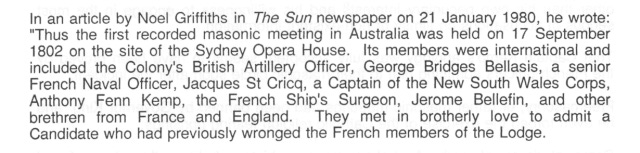

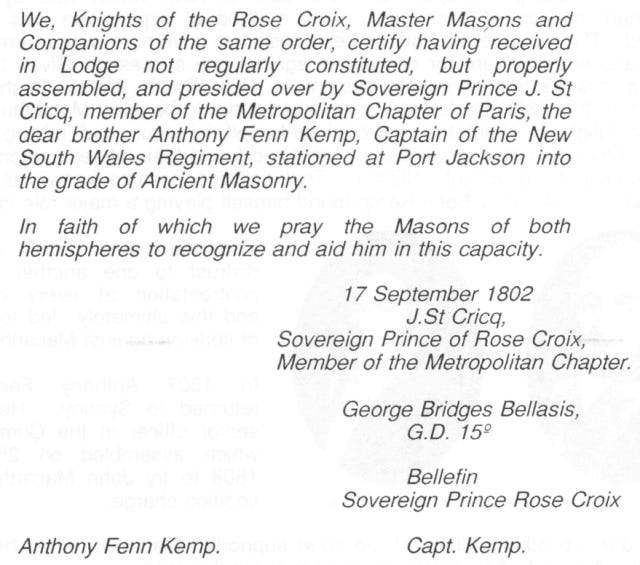

In 1802, there were reports of Masonic meetings held on board English ships at anchor in Sydney Harbour, attended by sailors, settlers and an Irish convict named Sir Henry Browne Hayes.

The Masonic Historical Society of NSW confirm this in a memo found deep in a 1999 newsletter:

Yet again, we can see that high elements of the Corps and other groups were working in secret.

Two French ships, the Naturaliste and Géographe, arrived in Sydney Harbour, as part of a scientific voyage of exploration of the Australian coastline. It is aboard these ships that the meetings were taking place.

The Masonic French were exploring parts of Australia and the South Pacific in the years around 1800, perhaps with a view to ousting the British from Australia before they had become well established.

All present were arrested when the meeting was interrupted by the military.

In a dispatch dated 21 August 1804, the Governor reported that “every soldier and other person would have been made a Freemason, had not the most decided means been taken to prevent it”.

King intervened, but not before Captain Anthony Fenn Kemp (listed above) had been admitted to the order of the Rose Croix, highlighting the importance of this Rosicrucian higher meeting.

A week prior to arrests, Sir Henry had written to London complaining that he had been forbidden to hold a Lodge and preside at initiations, despite being in possession of a warrant.

Later that month, an order was published forbidding meetings without the Governor’s express permission, in a move that sent shockwaves through the young colony at the time.

King also shut down a planned Masonic meeting in May 1803 with crew members from HMS Glatton.

Remember, this was an era when the population of Sydney was less than 10,000 people.

King continued to suspect ‘hidden conspirators’ when he was made for the next few years, reportedly sending two men to the triangles for 500 lashes each in 1804.

However, the Governor’s orders, which had the object of suppressing all Masonic activities in Sydney, were not enforced elsewhere in his jurisdiction.

This allowed the Freemason brotherhood the ability to regroup off-shore and plan their next moves.

SECRET MEETINGS

NORFOLK ISLAND

University of Sydney Professor Alan Atkinson has asserted “a benefit and burial society” was formed on Norfolk Island in 1793 by a Rousseau-devotee and about ninety others intent on regulation of prices.

Atkinson has assumed this society must have had Speculative Freemasonry as its model, arguing this can be seen in the provision where members were to be provided with part of their passage money should they decide to leave the island, whether for Europe or elsewhere.

He has claimed the Provost Marshal of Norfolk Island, Fane Edge, was a Freemason of the ‘ancient’ variety, and has asserted that these ‘lodge’ members planned an annual feast on St Patrick’s Day.

Fane Edge was enlisted in the New South Wales Corps on 6 March 1790. He was appointed town adjutant by Governor Arthur Phillip in February 1792, to draw him “out of the line of sergeants”.

According to reports, “he received no allowance for this position”.

When appointed by Phillip as provost-marshal of Norfolk Island in March 1792, he took charge of a group of convicts in the Pitt. One could assert it is here that Edge became compromised.

King, when he came to power, tried to convert it into a ‘settlers’ meeting’, shaped more to his liking.

In March 1802, Edge was “suspended by Lieutenant-Governor Joseph Foveaux for repeated disgraceful transactions which rendered him unfit for public office”.

A bit suspicious, don’t you think?

Thomas Restel Crowder and others reportedly held meetings without a warrant and seem to have been situated at Norfolk Island from 1800 to 1807, perhaps until 1814, according to Atkins

In 1796, then-Governor Hunter, reported that the British settlers on Norfolk Island included secret conspirators, for which traces still remain from that very time period.

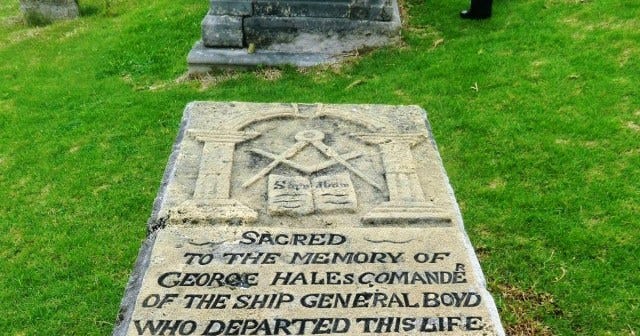

Evidence of Masonic presence is found in the old graveyards of the distant island, which includes George Hales, who died at aged 47 years on Norfolk Island after becoming sick.

He was commander of the whaling ship “General Boyd” which was in Sydney Harbour in June 1801.

His gravestone on Norfolk Island bears various Masonic symbols, including an open book below square and compasses, which lie between two pillars surmounted by an arch:

There is also fragmentary evidence of an unwarranted St John’s Lodge not only working, but in possession of a building and land, on the island of Norfolk Island in the first decade of the 1800’s.

That island was intended for the worst offenders, being isolated and situated in the SW Pacific hundreds of miles north east of Sydney. It seems perhaps this small island was used for much more.

Furthermore, when the First Fleet arrived in January 1788, a younger Phillip King was detailed to colonise Norfolk Island for defence and foraging purposes. He became very familiar with the place.

Could this explain his heavy resistance to Freemasonry when he became Governor?

Either way, it seems the grip of King and those before him was slowly loosening.

Issues on the mainland, particularly with the Mason-controlled trade route, began to lead to social unrest.

It was here the Freemason brotherhood would capitalise on the chaos.

King’s jitters seemed to be confirmed in March 1804, when some hundreds of the Irish convicts currently in the colony over instigating a rebellion at Castle Hill, near Parramatta.

Conflicts with the military wore down his spirit, and they were able to force his resignation.

However, perhaps to the dismay of the Masons, the next Governor would be even more harsh.

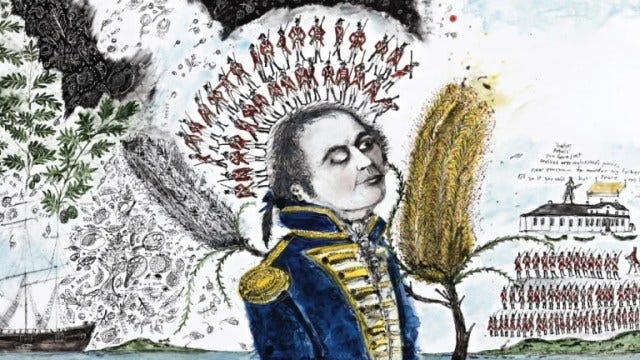

BLIGH: THE LAST TRUE GOVERNOR

In 1806, William Bligh, a British naval officer infamous for his strong, dictatorial ruling style, became the latest Governor tasked with putting an end to the rum trade and infiltrating activities.

Bligh implemented strong measures, including the destruction of illegal stills and the prohibition of using spirits to barter for grain, labour, food, or any other goods.

Although we haven’t mentioned Bligh in this piece yet, the man is actually making his return after an infamous mutiny in the southern seas which included some very familiar names.

BLIGH’S MUTINY

The expedition was promoted by the Royal Society and organised by Sir Joseph Banks, who shared the view of Caribbean plantation owners that breadfruit might grow well there.

However, it was on this journey that a young Bligh would find out the true nature of his expedition.

The mutiny on the HMS Bounty occurred in 1789 when the ship was under his command, after being set adrift in Bounty‘s launch by the mutineers. I mean, the ship is called ”Bounty’, mate.

Bligh and his loyal men were attacked and thrown off the ship, with all reaching nearby Timor alive. This was after a journey of 6,700 km. Bligh’s logbooks documenting the mutiny were inscribed on the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World Register on 26 February 2021.

THE RETURN

Seventeen years after the Bounty mutiny, on 13 August 1806, he was appointed Governor of New South Wales, with orders to clean up the corrupt rum trade of the (Masonic) New South Wales Corps.

He quickly began to make progress, building upon the strict rules introduced by the King-era.

So much so, that the Corps — including Rosicrucian Anthony Fenn Kemp — revolted against him.

It is here we connect the truths about Australia’s only successful armed takeover of a government.

THE RUM REBELLION

We have all heard of Australia’s famous Great Rebellion, also known as the ‘Rum Rebellion‘.

The rebellion of 1808 was a coup d’état in the then-British penal colony of New South Wales, staged by the New South Wales Corps in order to depose of Governor William Bligh.

I have heard people speak in a patriotic manner over this event whenever our current governments are acting up.

Many believe we should ‘take inspiration’ from a time when the establishment was overthrown.

However, as we have just laid the context for, there was much more to this event than meets the eye.

This was a Freemasonry move to overthrow the government. That’s why it is the only successful one.

Think about it.

According to the Wikipedia page on the Rum Rebellion:

“Bligh made enemies not only of Sydney’s military elite, but several prominent civilians, notably John Macarthur, who joined Major George Johnston in organising an armed takeover.”

That’s right, it was the Governor that had “made enemies” with “the elite”.

Those elite being, as we are exploring, a Freemason brotherhood.

Tell me again why we should ‘take inspiration’ from this event?

Although, you can’t blame people, as barely any records exist detailing the early Masonic influence that gripped Australian trade in the early days of settlement. Research was difficult for this one.

Why are we not told of the anti-Masonic government at the time? Or their struggles?

Why is Bligh remembered as the ‘top dog’ who fell at the hands of ‘noble citizens’?

NOT RUM, BUT MONETARY CONTROL

The event came to be known as the “Rum Rebellion,” but just how much it actually had to do with spirits depends on your interpretation of history.

A shortage of coins in Australia — something common in many British territories at the time — meant that “rum,” shorthand for all distilled spirits, was the favoured currency.

A complex barter system was developed that was controlled by those who had access to goods – particularly food, clothing and alcohol. Convicts and lower ranking military were regularly paid in goods, rather than money, and the most popular form of payment was rum.

The Masonic officers of the New South Wales Corps used their status and wealth to gain a monopoly on the country’s rum supply. This brought more wealth, and with it, power.

The Corps involvement in this system led to its nickname in the 1790s – the Rum Corps.

This is why Bligh was tasked with dismantling this corrupt operation once and for all.

Much like today, Bligh was faced with the reality that a secretive off-shore group was holding meetings and directing local affairs through the many trade avenues they owned.

Does that sound familiar to you?

By this time, the economy had allowed many individuals to become large influences in society, both in the industrial arena, but also in the eye’s of the public — who already opposed the State as convicts.

All of these combustible elements allowed the military to gain support for a revolt.

JOHN MCARTHUR: THE BARON

John Macarthur had arrived with the New South Wales Corps in 1790 as a lieutenant, and by 1805 he had substantial farming and commercial interests in the colony.

He had quarrelled with the Governors preceding Bligh and had fought three duels.

Some of the officers in the Corps, like Macarthur, became powerful and wealthy citizens. Macarthur was favoured with large land grants and other privileges under Lieutenant-Governor Francis Grose.

As Officer-In-Charge of the NSW Corps, Grose had temporary charge of the Colony after Governor Phillip left on a trip and appointed him to several official positions of influence.

The power wielded by Macarthur and others lead to clashes with the second and third governors, John Hunter and Philip Gidley King, who tried to eradicate the military’s monopoly on trade and crack down on drunkenness, but too much money and power was at stake and they failed.

Macarthur had an all-pervading, if not sinister influence in colonial affairs from that time on.

It would all culminate with the storming of the capital and arrest of Bligh in 1808.

THE EVENT/AFTERMATH

On the morning of 26 January 1808, Bligh again ordered that Macarthur be arrested and also ordered the return of court papers, which were now in the hands of officers of the New South Wales Corps.

The Corps responded with a request for a new Judge Advocate and the release of Macarthur on bail.

Later that day, 400 soldiers marched on Government House and arrested Bligh.

That’s right. The day we celebrate every year is marking the anniversary of when Masons stormed government offices and installed themselves in power for eons to come.

In the aftermath, Bligh was kept in confinement in Sydney, and then was put aboard a ship off Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land, for the next two years.

Bligh would retire and keep out of the public eye following this event, as the new Masonic brotherhood took total control of Australia, just as they had done in France, America and soon Ireland.

This was the moment Australia was changed forever.

And, as expected, many open Freemasons were directly involved with the armed revolt itself.

OTHER PLAYERS

ANTHONY KEMP – BACK AGAIN

Anthony Kemp, the soldier and merchant who was at the center of Governor King’s storming and arrest of ships docked in Sydney, has made his was to Deputy-Judge Advocate of the colony of New South Wales.

On the morning of the revolt, Kemp was the senior military officer on the Court of Criminal Jurisdiction, which had been called to try John Macarthur for the charge of sedition. They dropped the charges.

It should come as no surprise that Kemp, already a target of Governors, was positioned in this way.

Kemp and other officers informed Bligh that he should resign as governor and that his safety would be guaranteed out of the colony. Bligh refused, and the military removed Bligh from office.

Kemp returned to England in 1810 and was a witness at the court martial of Johnston for the Rebellion. Kemp escaped being court martialled himself, as expected

JAMES LARRA

James Larra, a Jew transported in the Second Fleet, was nevertheless said ‘to be well regarded by the authorities’, becoming principal of the nightwatch soon after his arrival in 1790.

He was pardoned in 1800 and became the most successful businessman in Parramatta.

It was Larra who had the ‘Masons/Freemasons Arms’ built at Parramatta before the end of the decade, and it was there that members of a key ‘French scientific expedition’ stayed in 1802.

He was involved in the earlier Castle Hill revolt when King was Governor, which forced him to pass on the reigns to Bligh and resign. This was the only evidence of Masonic-influence found in this event, but it wouldn’t surprise me if they had staged this smaller event of Irish prisoners prior to the Great Rebellion.

Remember, Ireland was ‘rebelling’ against Britain, and pro-new-world prisoners were a benefit to the Masons looking to shake things up in Australia. As Ireland was also being turned over to the Order.

GEORGE JOHNSTON (Masonic Leader)

Perhaps the most important player to highlight, George Johnston played a key role in this event by working closely with John Macarthur.

Johnston led the troops that deposed Governor Bligh, assumed the title of Lieutenant-Governor, and illegally suspended the Judge-Advocate and other officials.

In years leading up to the event, Johnston was put under arrest by Lieutenant-Governor William Paterson on charges of “disobedience of orders”.

Johnston objected to trial by court-martial in the colony, and Hunter sent him to England.

There, the difficulties of conducting a trial with witnesses in Australia led to the proceedings being dropped, and Johnston returned to New South Wales in 1802.

It was at this time he would get his revenge and lead the Rum Rebellion:

I looked a little further into this Johnston character, and it turns out he was a marine officer during the American Revolution, and even hosted early meetings of Masons during this time period in Wisconsin:

These are just a few examples.

I haven’t had time to look through the entire documented list of those involved in the Great Rebellion, but with everything found so far, I think this is definitely enough to raise red flags about this event.

Indeed, just like lands overseas, Australia was victim of a Masonic-led revolution.

Not only in similarities, but in the actual people who were present for both events (like Johnston).

After this event, the military remained in control until the 1810 arrival from Britain of Major-General Lachlan Macquarie, who took over as governor.

MACQUARIE: THE MASON GOVERNOR

In the aftermath of the Great Rebellion, on 8 May 1809, Lachlan Macquarie was appointed to the position of Governor of New South Wales and its dependencies.

On arrival, Macquarie (according to his Wikipedia) “was unchallenged by the New South Wales Corps”.

This is because, perhaps unbeknownst to the Empire, Macquarie has Masonic ties.

Governor Macquarie came from the Indian army, where Freemasonry was already popular.

Part of Macquarie’s undertaking of ‘bringing order’ to the colony was to refashion the convict settlement into an urban environment of organised towns with streets and parks.

The street layout of modern central Sydney is based upon a plan established by Macquarie.

In 1821, when he laid the foundation stone of the first Roman Catholic Church in Sydney, he was given a ceremonial silver trowel.

The game has been won, and the Masons had claimed Australia.

Macquarie would become the first of many members of the brotherhood to control positions of powers to the present day, responsible for a number of social and political reforms.

His lasting Masonic legacy is found in the name of the Port Macquarie Lodge, who dedicate the premise to the Governor himself on their website:

Soon, freemasonry was entirely respectable and becoming more widespread.

Macquarie allowed the rum trade to continue, only enforcing penalties on consuming the product in public. He also was responsible for the pardon of criminals to enter society as ‘productive members’.

Remember, many criminal convicts were sent here for revolutionary activities against the British state.

A state that clearly no longer had control over Australia.

Many men in the late 19th and early 20th century were photographed in their Masonic regalia. At a time when photography was new and expensive, sometimes such portraits are the only ones we have.

FROM TERRA AUSTRALIS TO AUSTRALIA

In 1814, the British 46th Foot Regiment arrived to staff the military garrison at Sydney.

This Regiment had a Lodge attached to it, holding a travelling Warrant No. 227 from the Grand Lodge of Ireland. Earlier, this Lodge had been in North America during the War of Independence.

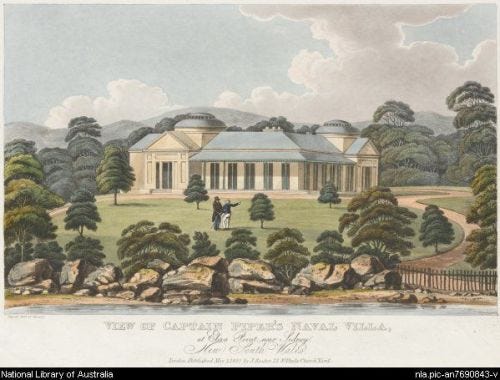

The first public Masonic ceremony in Australia was staged by the Lodge of Social & Military Virtues No 227 IC, on 2nd November 1816.

This was the laying of the foundation stone of Brother Captain John Piper’s home at Eliza Point, Sydney.

Some 32 Masons took part in the ceremony.

During 42 months military service in Australia, the Lodge initiated several candidates.

The first civilian Lodge was formed in 1820 after obtaining a Warrant from the Grand Lodge of Ireland

During the next decade, two more lodges formed in Sydney, and one in Hobart on the island of Tasmania to the south of the Australian mainland.

Matthew Flinders, the Mason who had arrived during early settlement, campaigned the changing of the country’s name from Terra Australis to Australia during this period. A final signal of the transformation.

By the 1840’s, Freemasonry no longer met with disapproval from the local authorities.

Rather, it was seen as an institution tending to ‘promote good’ order in society.

During the following 45 years, more Lodges were formed in many parts of settled Australia as the population expanded, holding allegiance to the Grand Lodges of Ireland, England and Scotland.

LODGES EXPAND

From the early years of the nineteenth century, the free settlers had sought some measure of political self-determination, which resulted in the establishment of a Legislative Council in New South Wales in 1824, due largely to the work of Bro. William Wentworth.

This, in turn, led the Freemasons to seek local control of their Masonic affairs, which resulted in a number of attempts to form local Grand Lodges independent from the parent bodies in Britain.

Over time, there was a similar line of Masonic development across the country.

In Victoria, which resulted in the establishment of the Grand Lodge of Victoria in 1883 with the Hon. George Selth Coppin, a Member of the Legislative Assembly, as the first Grand Master.

Eventually, the other colonies each formed a Grand Lodge with South Australia leading in 1884, Tasmania in 1890, Western Australia in 1900 and Queensland in 1904. United Grand Lodges were established in New South Wales in 1888, Victoria in 1889 and Queensland in 1921.

There is a correlation between political status and expansion.

Hon. Sir Samuel James Way, Chief Justice and a former Member of the House of Assembly, was the first Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of South Australia.

Hon. Sir William John Clarke, a Member of the Legislative Council, was the first Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of Victoria.

The first Deputy Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Tasmania was Bro. Dr. Edward Owen Giblin, who was also Member of the Tasmanian House of Assembly.

The Grand Master at the establishment of the Grand Lodge of Western Australia was the Hon. Sir John Winthrop Hackett, who was a Member of Western Australia’s Legislative Council.

By the 1800s there were more than 100 Lodges all over Victoria.

In 1883, the Grand Lodge of Victoria was established to oversee Freemasonry throughout Victoria.

Formed in 1888, the United Grand Lodge of Victoria had its first Installation at Melbourne Town Hall with over 6000 Freemasons in attendance.

It is here, in the late-1800s, that most records begin for Freemasonry in Australia.

By this point, as we have just explored together, there had already been a rich and storied history that nobody talks about.

Harping on the pursuit of material gain had left ‘our history’ with the idea that there had been no important social differences, when, in reality, the differences and thus the conflicts have been profound.

During the decades from the 1880’s to the 1920’s, advocates of nationalism had replaced ‘home’ values with foreign versions. Australia was now supposedly free of superstitions, traditions, class distinctions and sanctified fables and fallacies, of the older nations.

All while radicals within the labour movement had produced the creed of ‘the bushman’.

Bushmen that only spent their time waring with Indigenous populations, apparently.

Gradually, the men holding these opinions built up their own ideas of the past, including that of the Great Rebellion and the idea that Australia was the political and social laboratory of the world.

Perhaps the most striking example of the way in which this belief distorts and warps our writing of Australian history is in the interpretation of the events that happened.

Because of the country’s ‘thief colony’ image, and for many years a lack of proper information, Australians have suffered from intellectual and emotional difficulties in developing a view of their national origins.

The country had been taken over, and by this point, Britain was either to weak to fight back or had finally succumbed to the forces of the Rosicrucian-led Enlightenment period.

A period that destroyed the ideals of tradition and of the human.

This is the story of a small island, which despite being on the other side of the planet, was caught in a time of great transition from one version of reality and control, to the next.

From the moment the President of the Royal Society arrived with James Cook, to the military coup of Governor Bligh, Australia’s early hidden history is certainly one for the ages.

The rest, they say, is history.