Love, Death, and Whitman: Poet Mark Doty on the Paradox of Desire and the Courage to Love Against the Certitude of Loss

By Maria Popova: Brain Pickings.

Maria Popova is a Bulgarian born New York based polymath who has read everything so the rest of us don’t have to. Not just hyper intelligent, she has an uncanny eye for beauty combined with a deeply felt sense of what makes us human.

Born in 1985, her beautifully written book Figuring, a study, in essence, of the loneliness of genius before the internet age, was a major literary event.

https://asenseofplacemagazine.com/a-celebration-of-genius-maria-popova-and-figuring/embed/#?secret=udTIhBHRe9

Here is one of her most recent pieces. The original version can be found here.

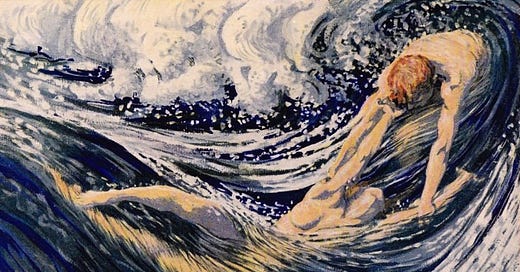

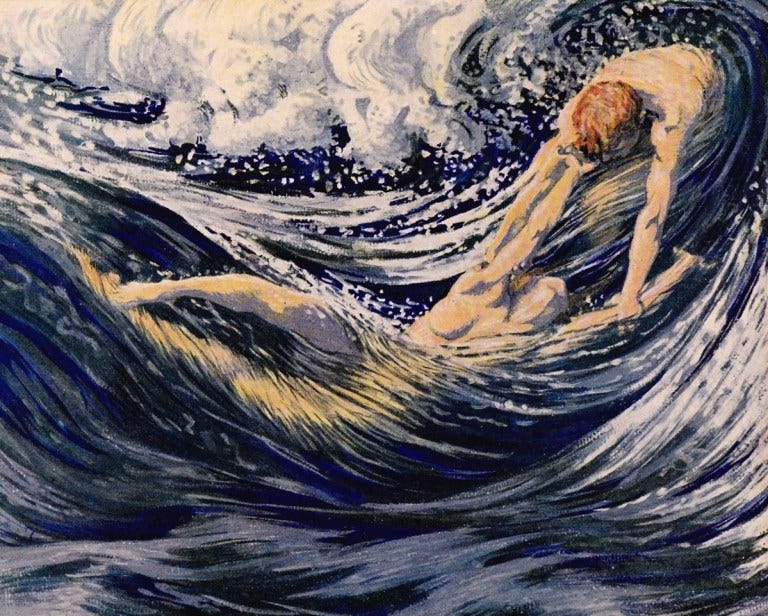

Love and death come to us on common terms — unbidden and total, impervious to protest, naked of pretension. They also come to us entwined: Every love is a franchise of grief, for to love anything is to accept its loss — by a dissipation of ardor or of atoms, the atoms constellating the beloved or the atoms constellating us and the consciousness that does the loving, certain to one day go the way of every other consciousness and every other love that ever was and ever will be.

In some deep sense, this inevitability of loss is precisely what makes love so ecstatic — a concentrated experience of aliveness consecrated by its own perishability.

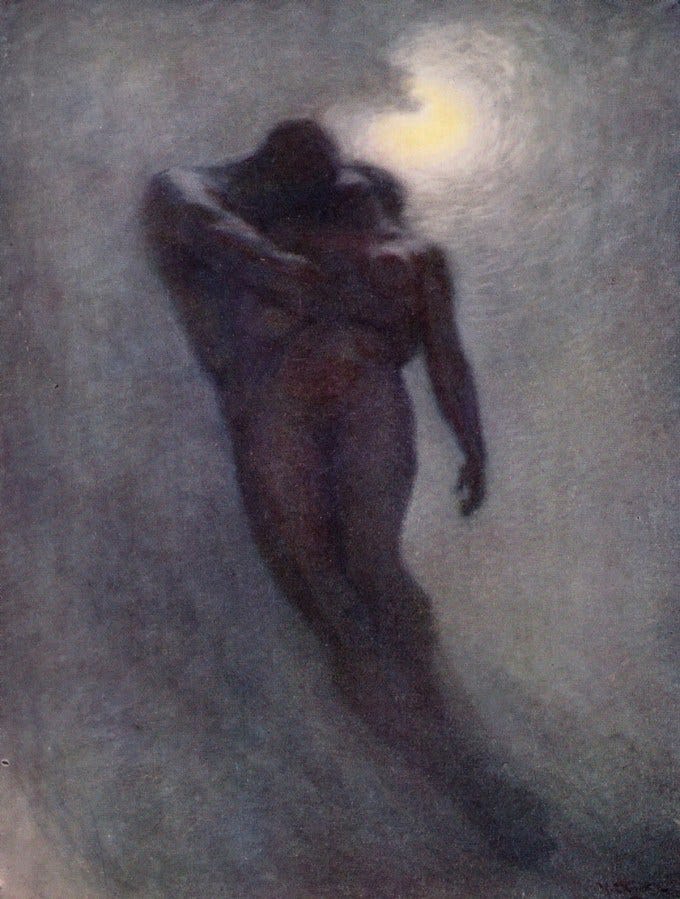

Walt Whitman touched on this with his tender, unflinching hand when he asked, “What indeed is beautiful, except Death and Love?”; when he observed that “to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.” He meant, I think, the luckiness of having lived at all, for death is only possible where life, improbable against the austere odds of the universe, once existed.

That inescapable interplay is what poet Mark Doty explores throughout his incandescent book What Is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life (public library) — part biography, part memoir, part lyric meditation on life, love, and their consanguinity with death.

Noting how deeply Whitman — the self-anointed poet of the body and poet of the soul — “understood that the particular is always perishing, and therefore all the more to be cherished,” Doty considers the body as an instrument of temporality and cherishment, through which the song of life sings itself and binds us to the chorus of all other bodies:

Begin with the body: water, vapor, air. You’re the shore on which an ocean of air is constantly breaking, in waves of breath. “Inside” and “outside” of lungs, permeable boundary of skin, eyes, ears, nose, holes in the body for substance passing in and out, no stable and fixed entity that is you, but a moving set of points through which pass water, air, light, food, parts of the bodies of others: their breath, tongues, genitals, hands.

[…]

The world enters us and departs, just as language and image and idea are imprinted upon our consciousness, considered, forgotten, passed on, released.

This perishable, permeable body, with its ceaseless entropic flow, lies at the heart of the paradox of desire — that electric impulse felt in the Body and felt in the Soul, furnishing our most palpable evidence that the two are one. “Behold,” Whitman wrote, “the body includes and is the meaning, the main concern and includes and is the soul.”

And so desire becomes a sacrament to the interleaving of love and death, temporal by definition and necessity, its temporality the wellspring of its delirium.

Awake to this fundament of feeling, Doty challenges the damaging Romantic ideal of interminable desire within any given love — a concept by nature self-negating, dishonouring the very thing that gives desire its electric charge:

Even in the imagined paradise of limitless eros, there must be room for death; otherwise the endlessness, the lack of limit or of boundary, finally drains things of their tension, removes all edges… The same body that strains toward freedom and escape also has outer edges, also exists in time, and it’s that doubling that makes the body the sexy and troubling thing it is. O taste and see. Isn’t the flesh a way to drink of the fountain of otherhood, a way to taste the not-I, a way to blur the edges and thus feel the fact of them?

The longing of the ephemeral body is the Borgesian mirror in which the eternal longing of the soul is endlessly reflected and reflected back, flickering with the bittersweet beauty of our mortal destiny, with the transcendent urgency of life and love. Doty writes:

You need to both remember where love leads and love anyway; you can both see the end of desire and be consumed by it all at once. The ecstatic body’s a place to feel timelessness and to hear, ear held close to the chest of another, the wind that blows in there, hurrying us ahead and away, and to understand that this awareness does not put an end to longing but lends to it a shadow that is, in the late hour, beautiful.

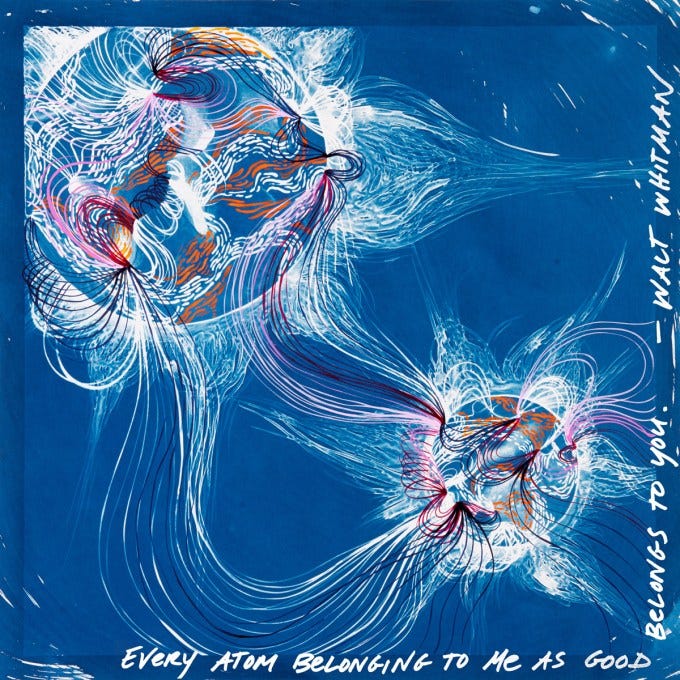

With an eye to Whitman’s central credo, staked on the poet’s ethos that “every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you” and that we are therefore not separate selves but contiguous territories of aliveness made all the more alive and more contiguous by love, Doty writes:

When the Self dissolves into a world of separate selves and death becomes real, love becomes a pact with grief; what is gained then is the inescapably poignant fact of individuality. There will never be another you, and I love the stubborn particularity of you because you will disappear.

Complement these fragments of Doty’s irreducibly splendid What Is the Grass with Hannah Arendt on how to live with the fundamental fear of love’s loss and Elizabeth Gilbert on love, loss, and the consecrating power of grief, then revisit Whitman himself on what makes life worth living.