Jac Vidgen and the RAT Parties

Farewell Old Friend

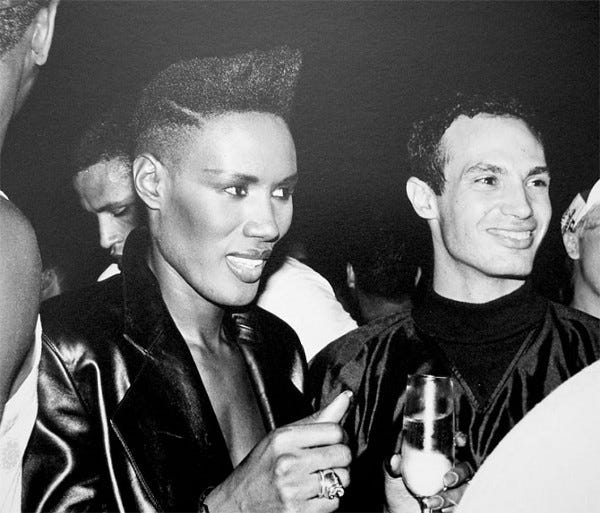

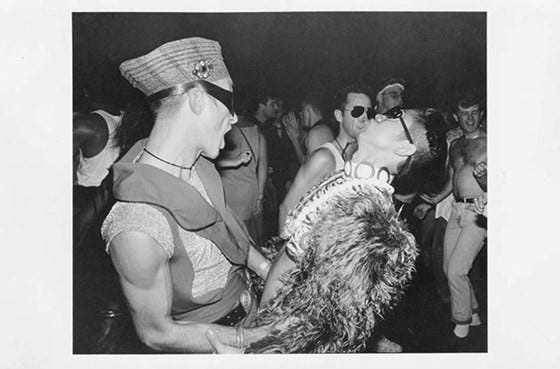

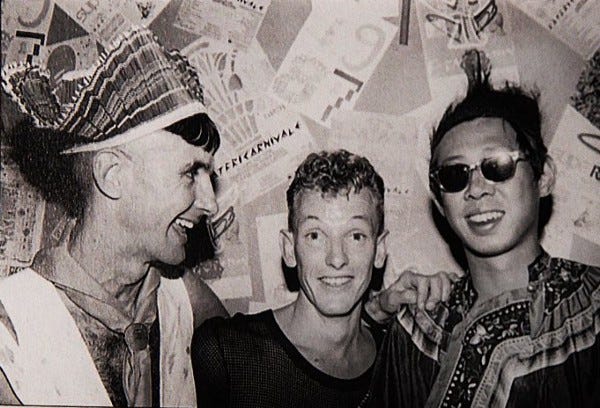

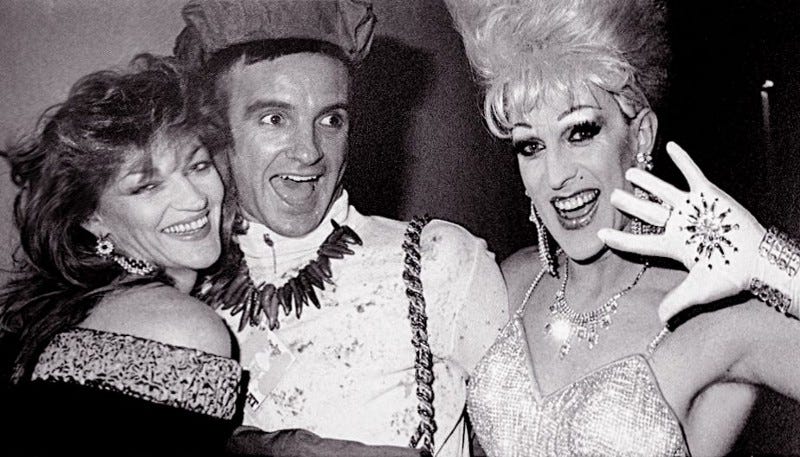

Jac Vidgen became both famous and infamous for one thing: his parties.

They grew from his lounge rooms in Elizabeth Bay in central Sydney in the 1970s, where I was a frequent visitor, to become truly massive affairs, attended by thousands, literally the biggest ever held in Australia.

The parties rode the wave of ecstasy, a drug designed for psychiatric patients to bring people closer to themselves, and thus to create empathy with others.

The patients took to the dance floor.

In their thousands. In their tens of thousands.

Surrounded by a psychotropic storm of swirling free range talent, enthusiasm and inspired creativity, Jac was the leader of the dance.

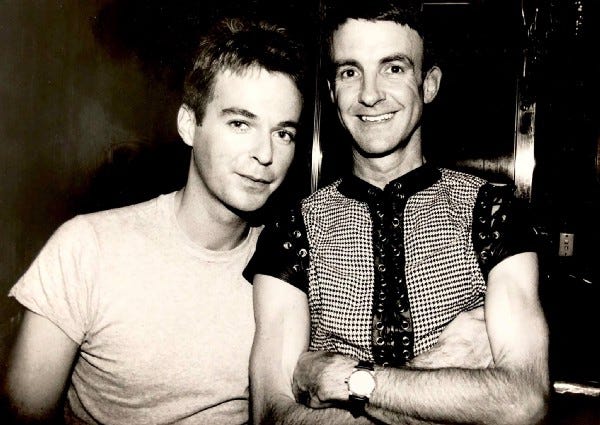

Everyone Came

Sydney will never see the likes of Jac Vidgen again.

Everyone knew Jac, and he knew everybody.

And they all came to his events.

Sydney Rave History records his thoughts:

I am honoured to have found myself being involved in the club and party scene in Sydney in the 80s.

It was a very vibrant and colourful era.

Many of the most outrageous and talented people who made a huge contribution to our events have already passed on — so I regard those of us who were there and who are still here to reflect on that wild time to be rather blessed and privileged.

I should say that I really found myself doing RAT almost by default, rather than by design — and I also want to acknowledge the many very talented and devoted people who teamed with us to make our events so extraordinary.

In an Interview with Vice Jac said:

The thing to understand is that drugs were far from the focus.

This is what distinguished RAT from all the other parties.

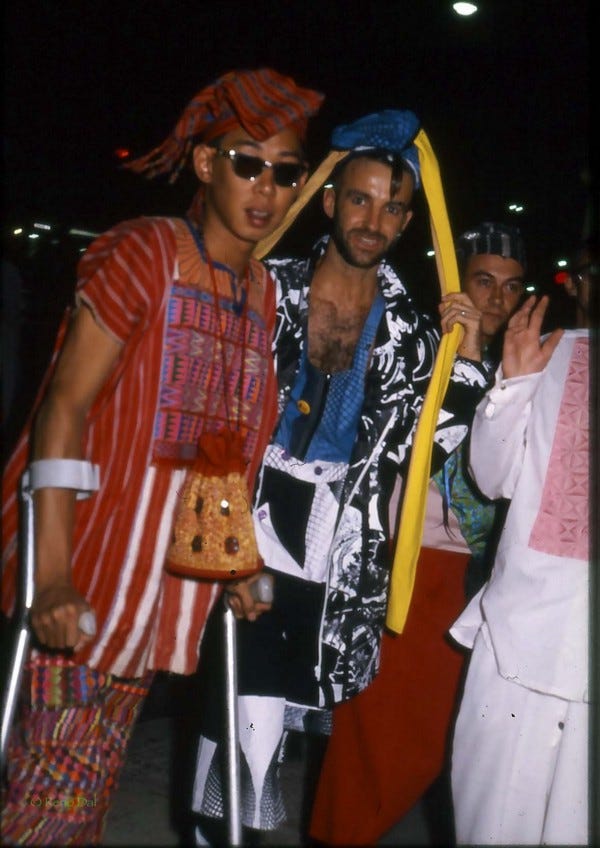

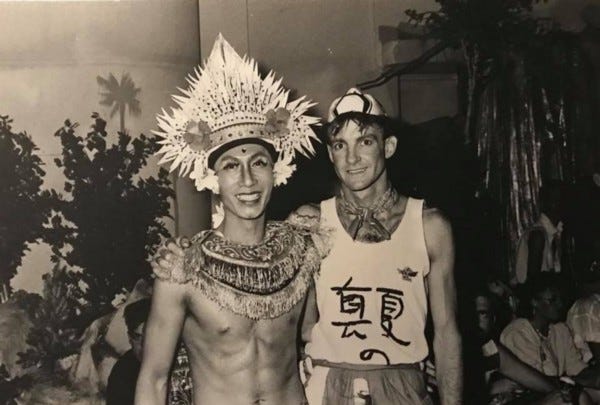

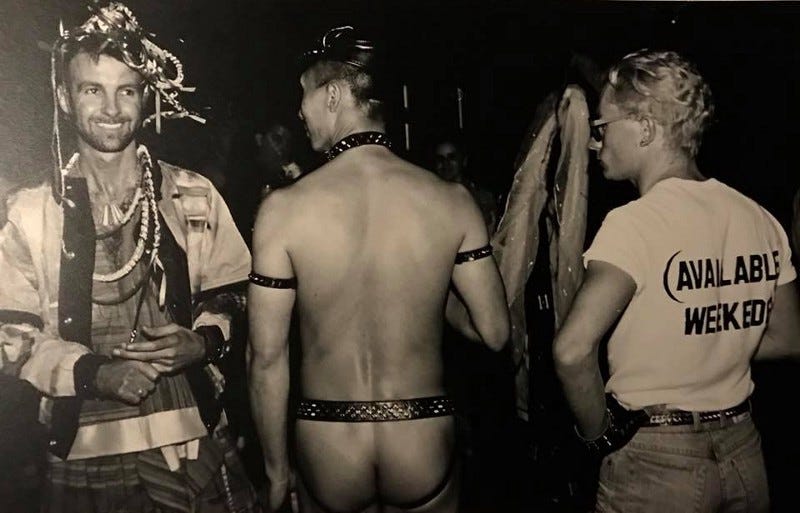

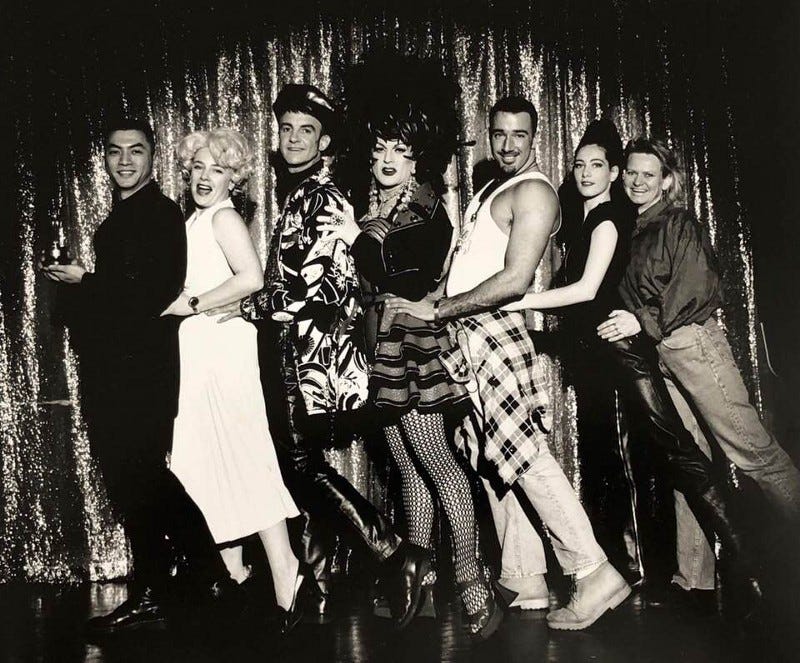

We’d put huge amounts of effort into creating an extraordinary environment where everyone got to be expressive.

Whether they were make up artists, fashion designers, costume makers or punters who wanted to be those things.

Or musicians who generally performed in front of 200 people who then got to perform in front of 2,000 people at our parties.

We gave people who weren’t famous a chance.

I used to just let people perform — not for long but it gave them a chance to be part of the event. I was privileged to work with some extraordinary people over the years.

It’s completely changed.

There was AIDS; that put a damper on things and so by the 90s people were going back to black.

Whereas the 80s had been an incredibly colorful period: colorful for fashion and colorful in a sense of people’s expression.

I think the 90s became darker and more conservative.

Sexually conservative as well, which was a rebound from the AIDS thing.

In the RAT photos, I could point out a lot of amazing people who are now dead.

There in the Crystal Light

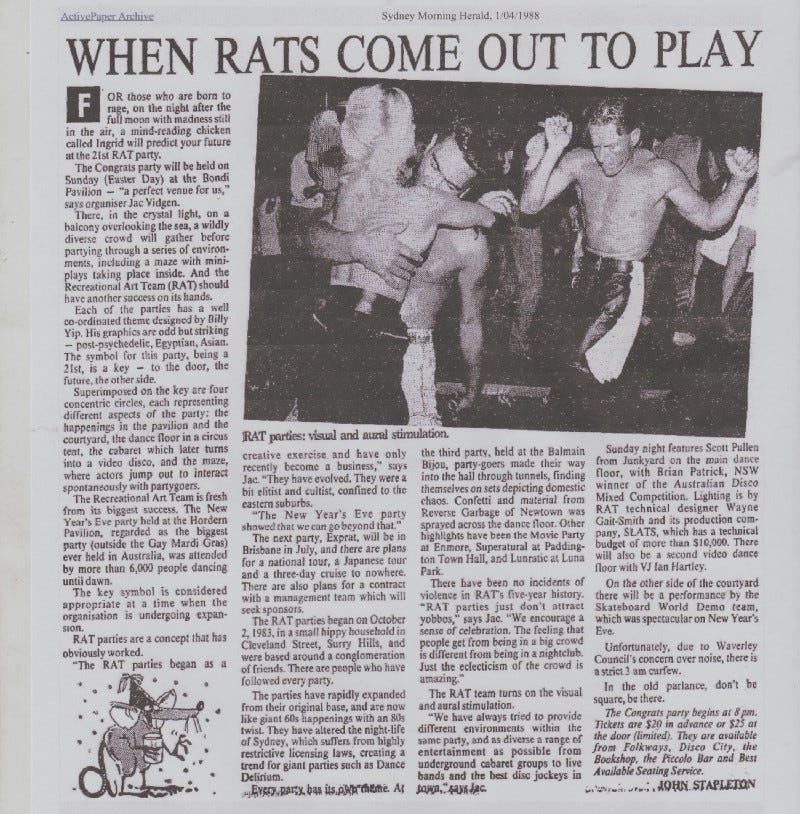

In a piece I wrote for The Sydney Morning Herald in 1988 I tried to capture the energy of the times for an upcoming event at the Bondi Pavilion:

For those who are born to rage, on the night after the full moon with madness still in the air, a mind-reading chicken called Ingrid will predict your future at the 21st RAT Party.

There, in the crystal light, on a balcony overlooking the sea, a wildly diverse crowd will gather before partying through a series of environments, including a maze with mini-plays taking place inside.

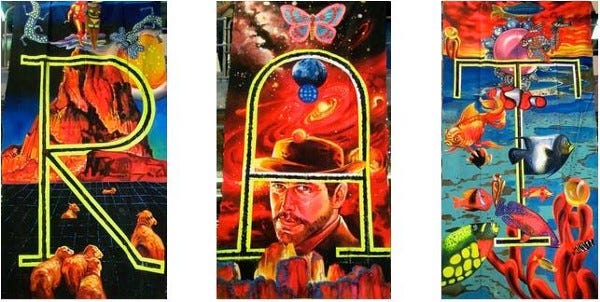

Each of the parties has a well-coordinated theme designed by Billy Yip.

The symbol for this one, being a 21st, is a key — to the door, the future, the other side.

Superimposed on the key are four concentric circles, each representing different aspects of the party: the happenings in the pavilion and the courtyard, the dance floor in a circus tent, the cabaret which later turns into a video disco, and the maze, where actors jump out to interact spontaneously with party goers.

There had been no incidents of violence in the parties five year history.

Jac said:

RAT parties just don’t attract yobbos.

We encourage a sense of celebration.

The feeling that people get from being in a big crowd is different from being in a nightclub.

Just the eclecticism of the crowd is amazing.

We have always tried to provide different environments within the same party, and as diverse a range of entertainment as possible from underground cabaret groups to live bands and the best disc jockeys in town.

It must have been strange interviewing someone I had known so long, from the days in the 1970s when we were just two refugees from the suburbs, delighted to have found our own inner-city milieu. To be able to go out all night every night if we wanted to.

Jac was fresh from his greatest success to date, a New Year’s Eve Party at the Hordern Pavilion where more than 6,000 people danced until dawn.

And I was working at that Bible of the Chattering Classes, The Sydney Morning Herald.

There was no cooler place for either of us to be at that particular little point in time.

Lure of the Illicit

There was a much earlier history, where we had a place. Be thankful that you knew it.

He makes an appearance in an unpublished novel I wrote called Lure of the Illicit, set back in the day. It covers a period when I have just returned from London. Bearing in mind that this was written in the 1980s:

The first buzzer I pushed was Jac’s.

He had grown even more mega-social than last I saw, life as a hyper-flit.

Visit him in the morning and he would be parading around whichever splendid Elizabeth Bay apartment he was occupying at the time, a bowl of muesli, grated apple and yoghurt in one hand. Or cross legged, back straight, doing his yoga.

And talking, always talking.

He was a social directory, always knew what everybody was up to, where to get a bit of this or that, lighting up connections.

I thought of him as a friend, though we hadn’t had a serious conversation in years.

Jac was now truly established as part of Sydney’s social scene. His parties, curious ragey affairs a bit like sixties happenings expanded into another decade, had grown larger and larger until they evolved into parties thousands of Sydney’s numerous ragers paid $20 or more to go to.

Ecstasy was de rigueur.

Sydney life was full of figures seen only occasionally, stories being enacted out in the distance. People came and went. Everyone was from somewhere else. All we had was a ledge, from which it was easy to disappear.

Willie Yang walked by on the other side of the street. For a while his book of photographs of Sydney people was on every coffee table.

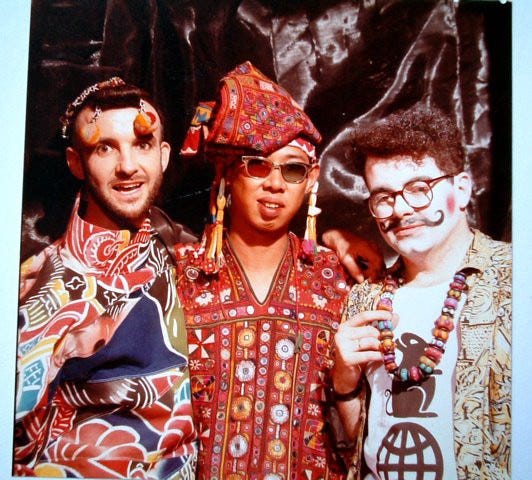

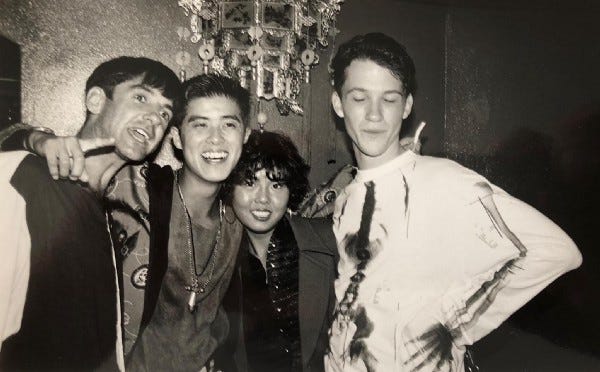

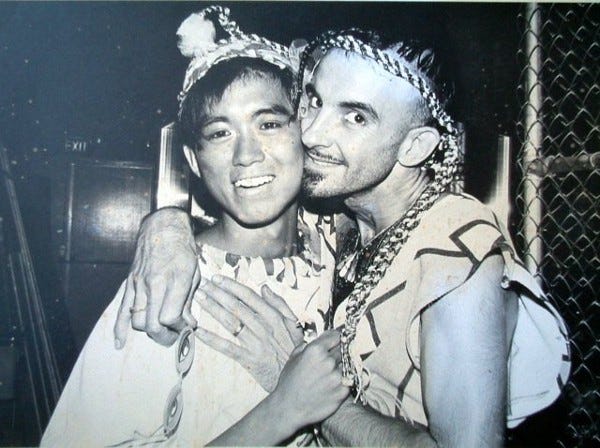

Jac usually had a passion for one Asian beauty or another. The last was Billy from Hong Kong, whose designs for the parties contributed to their curious nature.

Those Elizabeth Bay flats were filled with his idiosyncratic bric a brac, sunglasses draped silver statues laden with necklaces, odd mobiles. And Jac in the middle of it all, welcoming everybody.

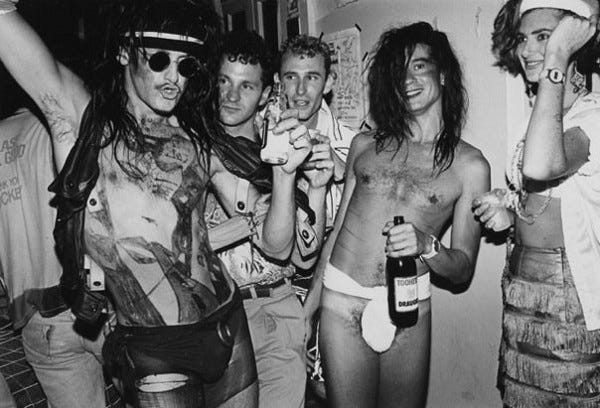

The Infamous Line

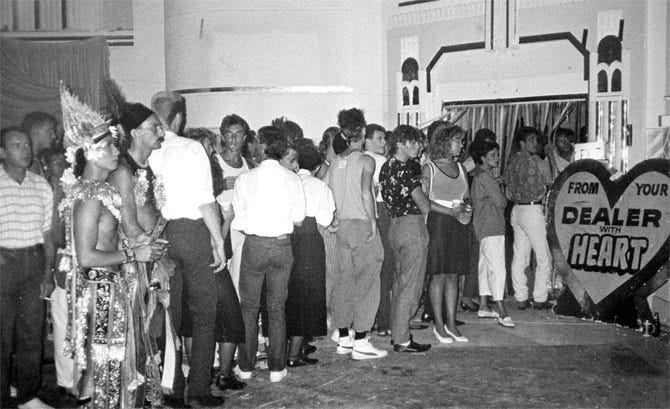

This photograph became so notorious it took on a name of its own, The Infamous Line.

These are a Jac Vidgen’s words, a blend of interviews published in Sydney Rave History and Vice:

It’s a photograph of people lining up at the Balmain Bijou in January of ’85 to buy their drugs.

The Bijou was a wreck in those days. We just took it over for a night and made it into this incredible environment.

What they’re lining up in front of is a big cutout foam sign that says “From Your Dealer With Heart,” which would have been a sign for a car dealer on Parramatta Road or somewhere.

I remember that night that the police came because we didn’t have a license.

I was wearing a Chinese or Japanese opera mask on the top of my head and I had these huge blousing red pants with white polka dots on them, a singlet that had been hand painted by somebody, and these long boots.

I was in quite the party mood and for some reason I told them that they should have a look inside.

I led these two policemen through a UV tunnel into the fantasyland of the party.

They stood there with their eyes practically popping out and said, “Right, well don’t do it again,” and then they just left.

We lived so long we became part of history

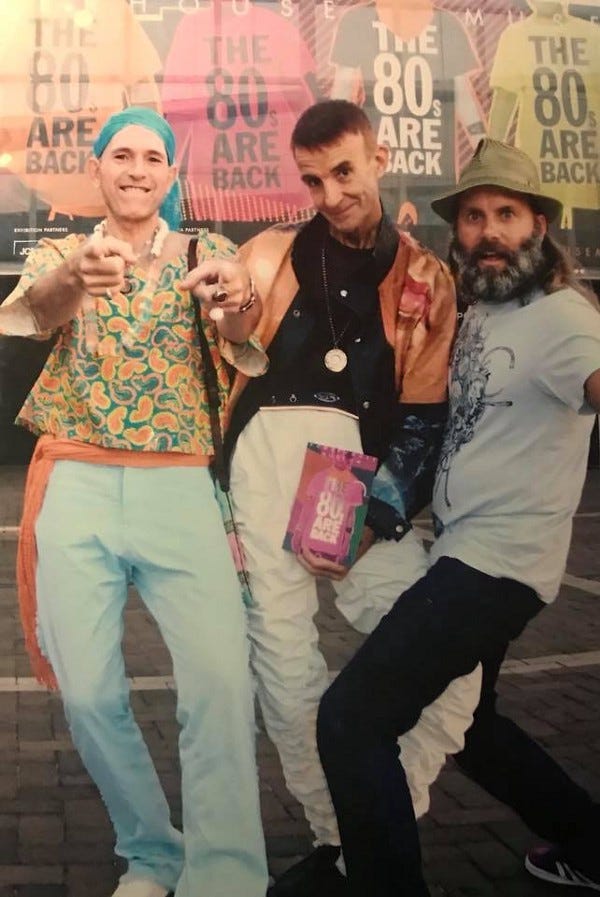

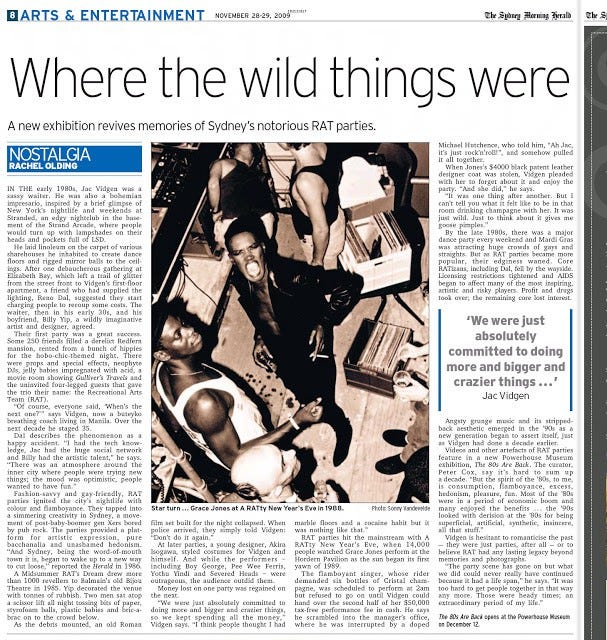

In 2009 the Powerhouse Museum held an exhibition recalling the wild days of the RAT parties.

Curator Peter Cox wrote:

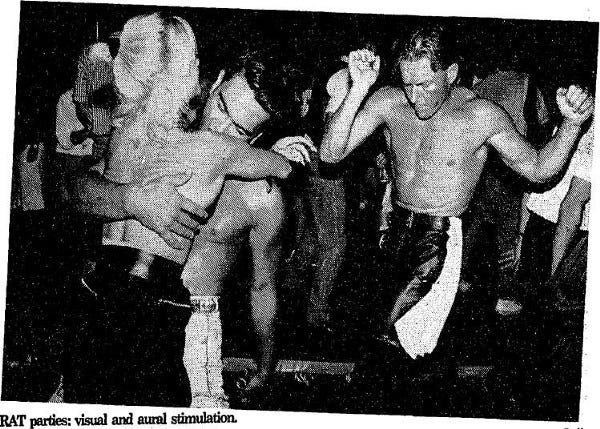

Vidgen threw his first public party for 200 guests at a rat-infested house on Cleveland St on 2 October 1983, because his own private parties had become too large and expensive.

He had no idea he was setting in train a phenomenon that led to a multitude of dance parties every year.The RAT parties altered Sydney’s , starting a craze for giant dance parties that lasted the 1990s.

They provided a diverse range of entertainment based on visual and aural stimulation, provided a creative outlet for talented people and set the tone and style of Australian dance music culture.

Or as as Jac told The Sydney Morning Herald:

“We were just absolutely committed to doing more and bigger and crazier things.”

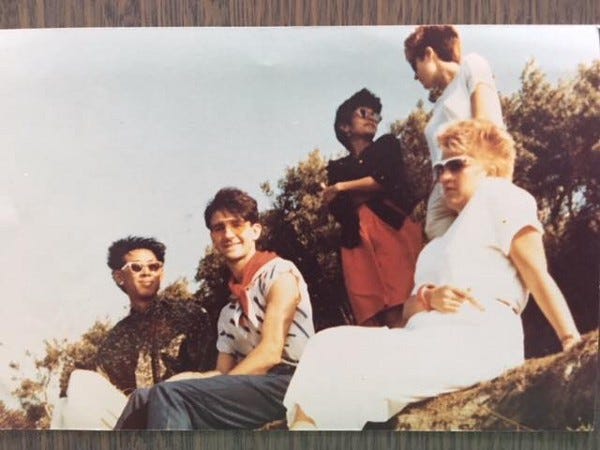

Clark Island, January 2018

The last time I saw Jac was at his traditional January picnic on Clark Island in the centre of Sydney Harbour.

Only Jac would have the grandiosity, good humour and know enough people to pull off such an event.

It was a vivid day on Sydney harbour, colour drenched, summer heat.

KJ Eyre writes: This lovely photo of Jac was taken by Floyd at the Clarke Island picnic on on 7/1/18.

It was Jac’s last full day in Sydney before returning to Manilla.

He is pictured here with some of his delightful Vidgen relatives. A special place, a special moment, a special man.

For me it was as if we were all from another place and only our holograms had been sent through to Clark Island.

As if in the vast flood something had been forgotten. Perhaps it was Optimism. Perhaps it was Youth.

An emotional disconnect.

In the day we had always assumed life would be an ever upward spiral, ever more fabulous. We would die old, rich, celebrated.

Now we knew all too well things rarely ended up the way we hoped.

“We slept together once,” Jac said on Clark Island that day, in a moment of hilarity.

“Do you remember?”

I shook my head.

No recollection whatsoever.

“We’d been out all over town, God knows where, and then we woke up in the morning in bed at my place.

“I looked at you and said, ‘John Stapleton!’ You looked at me and said, ‘Jac Vidgen!” And then we thought, well we’re here now.”

We both laughed. And then he was off, circulating. Always circulating.

Clark Island, September, 2018.

Jac Vidgen died unexpectedly in Manila, where had been living for some years, in May of 2018.

Although his closest friends said he had been unwell for some time, he seemed perfectly fine to me. Thin, but he was always thin.

“Godfather of Sydney’s Gay Dance scene passes away,” declared the headline in The Star Observer.

Vidgen’s massive dance parties changed the face of Sydney’s nightlife.

His close friend and fellow party promoter Richard Weiss told the paper:

“Jac Vidgen had a big heart and an open mind. He never lost his sense of wonder, his appreciation of beauty or his desire to be at the very centre of things.

“I thought he would live forever. I think most people did.

There was a surreal element to the announcement of his death.

None of us could hold back time. Too many had already gone.

We could never see tomorrow, no one said a word about the sorrow.

Al Green.

It was typical of Jac’s natural theatrical flair that the weather gods would turn on a perfect Sydney day for his Memorial.

After a week of miserable weather and scudding skies Sunday 9 September, 2018, dawned with barely a whisper of cloud in the high altitudes.

Renowned photographer William Yang, as he had done for decades, documented the event.

Tribute speeches broadcast from the boat washed across the lawn.

Fair enough, I only heard bits and pieces.

He was confronted with the widening girth of old friends.

“I knew that person when he was someone else,” one of them said as someone or other lurched or sailed by.

They both laughed.

“Jac catered to people’s one need: to celebrate.”

“I never expected to discover such an underground in Australia.

“Jac was influential and determined. He helped me get me get my permanent residence. He introduced me to numerous talent.”

“Your compassion inspired all of us.”

“I am where I am because of things you did, Jac.”

One speaker quoted Jac opposing a reignition of the RAT Parties, insisting they were of a time and place.

I am happy with what I did.

Perhaps as the only one who knew the whole story, whatever it was, as the event entered its final phase he stood, transposed into the third person, out on the pier with Billy Yip, away from the crowd.

He felt like he was beginning to swarm and was doing everything he could to try and stop it.

He looked into Billy’s face and was hit with an emotional thud. Feelings he could never bear.

Try as he might, all around him the harbour was swarming, drenched in colour.

Billy Yip

Billy Yip was 28-years-old when he first moved to Sydney from Hong Kong in the early 1980s.

“I met Jac two or three weeks after I arrived. It was at the Float Palace, which was a short-lived disco on Oxford Street near where Stonewall is today. Eye contact, that sort of thing. Simple. Very common. No electricity. He wasn’t my type actually.

“But I wanted to start a new life. Within a few days I moved in with him, and we stayed together for perhaps one and a half years. I didn’t have much feeling at first, but after that I was infatuated.

“The relationship went on.”

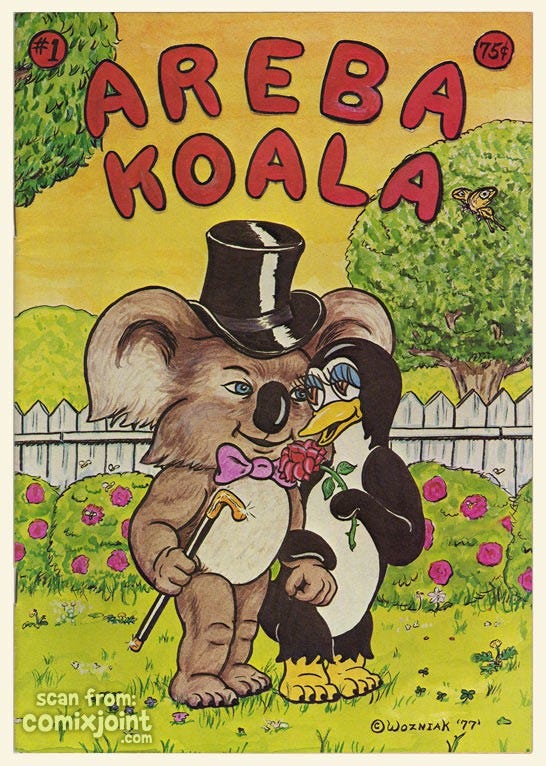

Speaking at his memorial Billy Yip said: “John, Jac, my sweet Areba, thank you for your tenderness for 30 something years.

“Please make me a juice still and may I crack a joke for you?

“You looked for beauty and perfection, and you were such a kind, natural man.

“You are my soulmate. As we all know you were very social, but you told me lately of your loneliness.”

Later Billy explained: “Jack always said he was Areba the Koala, and I was Babel the Penguin. He always called me Babel, and I called him Areba.

“The last time I saw him, the passion was going away.

“He had been hurt by a relationship. He was sick and just fading out.”

The last messages Billy received, in May, spoke of not feeling well: “Body pain, stiffness, high pulse, some fever, some cough — brown mucous! Very challenging.”

The last message, shortly before his death, read: “Not good. at talk must rest. I have had help. thanks xxx.”

That was on Saturday May, 26.

“The message was so brief. Normally he would talk for hours.”

Jac’s body was found on the floor in the kitchen with dried up blood all around him.

On that morning, Tuesday, May, 29, Billy received another message, sent using Jac’s Skype by another of Jac’s old boyfriends, Ed Cruz.

“Sad news Billy, found Jac dead in his apartment just this morning but looks like he’s been dead for two days. Just waiting for the police.”

“When the party is over, there is nothing,” says Billy. “Just a few photographs.”

These are the lines Billy wants to remember Jac by:

And I wanna rock your gypsy soul

Just like way back in the days of old

Then magnificently we will float into the mystic

When that fog horn blows

You know I will be coming home

And when that foghorn whistle blows

I gotta hear it, I don’t have to fear it.

Van Morrison, Into the Mystic.

Vale Jac Vidgen

We Came To Celebrate. We Came to Have the Time of Our Lives.

There are so many stories about Jac. He connected, influenced and interacted with thousands of people.

In a world that has become all about connectivity, Jac was a precursor to everything.

We can only close with a random tale.

There were so many soundtracks, so many wonderful characters, so much talent.

Photographer and musician Tim Ritchie remembers:

The first RAT party I played at was at the Paddington Town Hall and had me

teamed up with long time friend, sadly also gone, Robert Racic.

Jac’s idea was to have us as gods overseeing the dance floor in a temple built with scaffolding. Which was fine during soundcheck, but once the room was full and pumping, the scaffolding bounced, so did the turntables… and the needle left the groove!

Jac quickly hired some lads to hold down the turntables for the rest of the night. It ended up making us look even more like gods with these young men appearing to worship at our turntables in an house music induced prostration.

John Stapleton worked as a staff reporter for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian for more than 20 years. A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.