How Steinbeck Used the Diary as a Pacemaker for the Heartbeat of Creative Work

Maria Popova: Marginalian.

A Sense of Place Magazine is an unabashed fan of Maria Popova’s celebrated blog Brain Pickings, easily one of the best and most accessible literary journals in the world. The blog has been recently renamed The Marginalian.

Maria Popova is a Bulgarian born New York based polymath who has read everything so the rest of us don’t have to. Not just supremely intelligent, she has an uncanny eye for beauty combined with a deeply felt sense of what makes us human.

Born in 1985, her beautifully written book Figuring, a study, in essence, of the loneliness of genius before the internet age, was a major literary event.

https://asenseofplacemagazine.com/a-celebration-of-genius-maria-popova-and-figuring/embed/#?secret=udTIhBHRe9

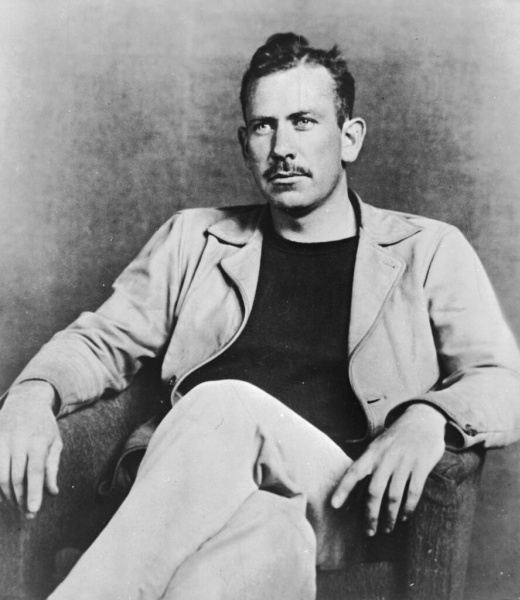

Here is an extract from Maria Popova’s journals of John Steinbeck, author of The Grapes of Wrath, and a writer of renewed significance in the current era . The original story can be read at Brain Pickings here.

“Just set one day’s work in front of the last day’s work. That’s the way it comes out. And that’s the only way it does.”

Many celebrated writers have championed the creative benefits of keeping a diary, but no one has put the diary to more impressive practical use in the creative process than John Steinbeck (February 27, 1902–December 20, 1968). In the spring of 1938, shortly after performing one of the greatest acts of artistic courage — that of changing one’s mind when a creative project is well underway, as Steinbeck did when he abandoned a book he felt wasn’t living up to his humanistic duty — he embarked on the most intense writing experience of his life. The public fruit of this labor would become the 1939 masterwork The Grapes of Wrath — a title his politically radical wife, Carol Steinbeck, came up with after reading The Battle Hymn of the Republic by Julia Howe. The novel earned Steinbeck the Pulitzer Prize in 1940 and was a cornerstone for his Nobel Prize two decades later, but its private fruit is in many ways at least as important and morally instructive.

Alongside the novel, Steinbeck also began keeping a diary, eventually published as Working Days: The Journals of The Grapes of Wrath (public library) — a remarkable living record of his creative journey, in which this extraordinary writer tussles with excruciating self-doubt (exactly the kind Virginia Woolf so memorably described) but plows forward anyway, with equal parts gusto and grist, driven by the dogged determination to do his best with the gift he has despite his limitations. His daily journaling becomes a practice both redemptive and transcendent.

Steinbeck had only two requests for the diary — that it wouldn’t be made public in his lifetime, and that it should be made available to his two sons so they could “look behind the myth and hearsay and flattery and slander a disappeared man becomes and to know to some extent what manner of man their father was.” It stands, above all, as a supreme testament to the fact that the sole substance of genius is the daily act of showing up.

teinbeck captures this perfectly in an entry that applies just as well to any field of creative endeavor:

In writing, habit seems to be a much stronger force than either willpower or inspiration. Consequently there must be some little quality of fierceness until the habit pattern of a certain number of words is established. There is no possibility, in me at least, of saying, “I’ll do it if I feel like it.” One never feels like awaking day after day. In fact, given the smallest excuse, one will not work at all. The rest is nonsense. Perhaps there are people who can work that way, but I cannot. I must get my words down every day whether they are any good or not.

The journal thus becomes at once a tool of self-discipline (he vowed to write in it every single weekday, and did, declaring in one of the first entries: “Work is the only good thing.”), a pacing mechanism (he gave himself seven months to complete the book, anticipated it would actually take only 100 days, and finished it in under five months, averaging 2,000 words per day, longhand, not including the diary), and a sounding board for much-needed positive self-talk in the face of constant doubt (“I am so lazy and the thing ahead is so very difficult,” he despairs in one entry; but he assures himself in another: “My will is low. I must build my will again. And I can do it.”)

Above all, it is a tool of accountability to keep him moving forward despite life’s litany of distractions and responsibilities. “Problems pile up so that this book moves like a Tide Pool snail with a shell and barnacles on its back,” he writes, and yet the essential thing is that despite the problems, despite the barnacles, it does move. He captures this in one of his most poignant entries, shortly before completing the first half of the novel:

Every book seems the struggle of a whole life. And then, when it is done — pouf. Never happened. Best thing is to get the words down every day. And it is time to start now.

JOHN STEINBECK

Steinbeck’s commitment to discipline isn’t mere moral vanity or fetishism of productivity — his is an earnest yearning to create the greatest work of his life, the height of what he as a conscious and creative human being is capable. In one of the early entries, he resolves:

This must be a good book. It simply must. I haven’t any choice. It must be far and away the best thing I have ever attempted — slow but sure, piling detail on detail until a picture and an experience emerge. Until the whole throbbing thing emerges. And I can do it. I feel very strong to do it.

But per Dani Shapiro’s astute distinction between confidence and courage, this is a statement of the latter, the truer virtue — Steinbeck is well aware of everything that might derail his efforts, vexations both external and internal, and yet he decides to exert himself anyway, to be wholehearted about the endeavor despite a profound lack of confidence. Here is courage, alive and throbbing, from another of the early entries:

All sorts of things might happen in the course of this book but I must not be weak. This must be done. The failure of will even for one day has a devastating effect on the whole, far more important than just the loss of time and wordage. The whole physical basis of the novel is discipline of the writer, of his material, of the language. And sadly enough, if any of the discipline is gone, all of it suffers.

So single-minded is his sense of purpose that in one entry he declares:

Once this book is done I won’t care how soon I die, because my major work will be over.

In some entries, he goes through the entire cycle of self-doubt, self-consolation, and crystalline awareness of the whole experience in a single stream-of-consciousness paragraph. Here is one from September 7, about a month away from finishing:

Dreamy sleep and coughing from too much smoking and confused by too many things happening and pretty worn out from too long work on manuscript. Have to cut down smoking or something. I’m afraid this book is going to pieces. If it does, I do too. I’ve wanted so badly for it to be good. If it isn’t, I’m afraid I’m through in more ways than one. Carol is working too hard now, too. And I’ve been with this book so long now that I don’t know much about it, I’m afraid. Well — have to take that chance. After all, if only I wouldn’t take this book so seriously. It is just a book after all, and a book is very dead in a very short time. And I’ll be dead in a very short time too. So the hell with it. Let’s slow down, not in pace or wordage but in nerves. I wish I could do that. I wish I would write only one page a day but I can’t. Got to go on at this rate or suffer for it. It must go on. I can’t stop.

Indeed, he frequently turns to the diary as a form of self-soothing, as much a mechanism for mobilization as one for calming himself:

This book is my sole responsibility and I must stick to it and nothing more. This book is my life now or must be. When it is done, then will be the time for another life. But, not until it is done. And the other lives have begun to get in. There is no doubt of that. That is why I am taking so much time in this diary this morning — to calm myself. My stomach and my nerves are screaming merry hell in protest against the inroads. I won’t be glad when it is done so why try to hurry it done? Now, I hope I calm down enough to start work again.

Underpinning all his practical frustrations and commitment to the writing process is Steinbeck’s larger philosophical awareness of the flash of presence we call life and the way in which we so often mistake the doing for the being:

So many things are happening. This is probably the high point of my life if I only knew it.

To Read the Full Story:

https://www.themarginalian.org/2015/03/02/john-steinbeck-working-days/