Gore Vidal at the Claridges

LIVING IN LONDON in the 1980s, by the time I got to Gore Vidal I was a bit blasé about interviewing famous people. I had interviewed Norman Mailer, Anthony Burgess, Dirk Bogarde, Salman Rushdie, the founder of the Sex Pistols, you name it; and while Gore Vidal might have been one of the most celebrated writers on Earth, doing the interviews alone just didn’t seem like much fun anymore.

There was no one to gossip with afterwards about what a rude, fascinating or eloquent person the target was, what other questions should have been asked, what a vacuous waste of space the PR person was.

So for Gore Vidal I took along a lesbian friend called Liz who I fancied enormously, much to the chagrin of her girlfriend. In those days everybody slept with everybody, David Bowie had declared himself bisexual, and as far as I was concerned, jealousy was the greatest sin. Gore Vidal himself believed bisexuality was the norm for both men and women. If only people were honest about it.

Also in our little entourage was the then editor of the London Gay Times.

I had become friendly with the staff on the city’s leading gay magazine after writing a story called On Being A Cold Australian and then walking it into their offices on the off. Like many an editorial office, the staff were bored and appeared to enjoy the diversion.

Back then I might also have been a little bit more aesthetically pleasing. The world is full of old men and their regrets.

Never mind all that, they published the story and kept on publishing or commissioning others; and I kept get invited to the editor’s home and to his parties, which were just great parties.

London in the 1980s was going off.

Gore was staying at the famous London hotel Claridge’s, where I had also interviewed Dirk Bogarde. The Connaught was his favourite London hotel, and for a time I thought I might have got the two confused. Even little histories rewrite themselves. But I remember him complaining he wasn’t at his normal digs.

Gore Vidal was a large man. While it may be world renowned and dazzlingly expensive, the rooms at Claridges were small by modern standards.

Gore Vidal was a large man and when he opened the door he seemed to take up all the available space.

He blinked in surprise at the sight of three of us when he was expecting a lone reporter, but quickly rose to the occasion.

“Do come in,” he boomed. “Please don’t be overwhelmed.”

I explained who we each were, said I hoped he didn’t mind that there were so many of us, and Gore, quick on the uptake, immediately settled into being entertaining and hospitable for the next hour.

I mentioned that I had recently been in Morocco and seen the author of The Sheltering Sky Paul Bowles, who I knew he was friendly with.

This led him to relate his own Moroccan story in hysterical detail.

Gore Vidal on the Tangier docks

Truman Capote, the author of In Cold Blood and Breakfast at Tiffany’s, was at the height of his fame when he decided that like William Burroughs, Tennessee Williams and the already legendary Bowles, he himself would visit Morocco.

But unlike everybody else, who just arrived and left Tangiers by common modes of transport, Capote had to do it in the grand style.

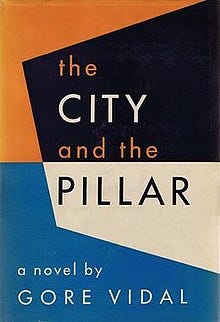

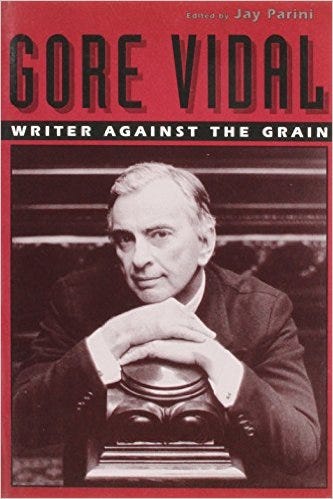

Gore Vidal, born into privilege, always supersmart, had been a successful writer from his very first book, published when he was just 21, The City and the Pillar.

The book was described by eminent literary raconter Bernard Levin as “the first serious American homosexual novel”.

Vidal regarded Capote as nothing but a horrid, preening little imposter.

The hatred was mutual.

Capote had loathed Vidal ever since Gore had the temerity to write a hostile review of one of his books.

Capote preferred to be adored by all. From the heights of his fame, he died surrounded by pill bottles. Vidal is said to have described his death as a “wise career move”.

Knowing that Gore Vidal was the last person on earth Capote would want to see as he made his triumphant arrival in Tangiers, Vidal flew from his home in Italy to Tangiers for the day of his arrival.

Well ahead of schedule, Gore planted himself firmly in the centre of the Tangiers docks.

A large white man in the midst of the crowds of dark Moroccans, he was more than conspicuous, which was just what he wanted.

As his ship came into the docks, Capote, who Gore described as looking like a little Southern senator in a green suit, came out on deck to wave to his adoring fans.

Capote always assumed that any crowd he faced was made up of adoring fans.

In reality most of the Moroccan workers on the dock wouldn’t have had a clue who he was.

As Truman’s eyes scanned across the always crowded docks, his hand half-raised in a kind of royal wave, it was impossible not to spot Gore Vidal standing there, staring straight back at him.

As Vidal told it, Truman’s royal wave froze and his face dropped.

Paul Bowles is recorded as describing the incident thus: “Truman Capote fell apart when he spotted Gore Vidal. His face looked like a soufflé that had suddenly been put in the freezer. He even broke down for a few seconds and went behind the bulwark to regain his composure.”

Vidal then turned and did the around trip back to the airport, flying home to Italy.

It was worth the effort, he said, just to see the look on Truman’s face.

Vidal was in the midst of his series on American Presidents and I asked some questions on the ostensible purpose of the interview, but for much of the time he regaled us with various tales he knew would amuse us. It was one of the single most entertaining interviews I’ve ever done.

Losing faith in the American project

Despite all the books he had written on American Politics, Lincoln, American Presidents, Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, he increasingly lost faith in his own country.

Along with Noam Chomsky Gore Vidal was one of the only public intellectuals to speak about the rush to war post 9/11.

In an interview with The Times of London three years before his death Vidal predicted: We’ll have a dictatorship soon in the U.S.

The War on Terror was just made up, he said.

“The whole thing was PR, just like ‘weapons of mass destruction’.

“Don’t ever make the mistake with people like me thinking we are looking for heroes. There aren’t any and if there were, they would be killed immediately. I’m never surprised by bad behaviour. I expect it.”

We leave him with Tariq Ali

Gore had always moved easily amongst the world’s cultural and intellectual elites; and as the interview wound up I remember being impressed by his next visitor — apart from Rushdie the most famous Indian writer and journalist of the day, Tariq Ali. Solidly left. Highly intelligent. Seemed to be in The Guardian every other day. A dazzling world of the intellect and the top echelons of society denied us mortals from the provinces.

“One thing I have hated all my life are LIARS and I live in a nation of them. It was not always the case. I don’t demand honour, that can be lies too. I don’t say there was a golden age, but there was an age of general intelligence.”

Even way back then Ali had already published half a dozen books.

His latest, The Dilemmas of Lenin: Terrorism, War, Empire, Love, Revolution, published last year, is a door stopper re-evaluation of the man who turned Russia into a one-party communist state.

They greeted each other like old friends as we three, scruffy in contrast to the padded luxury of Claridge’s and their own well-heeled sartorial garb, made our way down the hall and out into the muddy light of London streets, and back to our far more humble dwellings, our squats. In the days when all you had to do was get through the door of London’s many vacant apartments, change the locks, rig up the electricity and you could squat some of the best places in England. All thanks to English property laws dating back to the days of the Crusade.

We had a magnificent pad just around the corner from the British Museum and just up the road from Trafalgar Square. It belonged to London City Council, and they did not come a knocking for years. Amazing where a bit of initiative will get you.

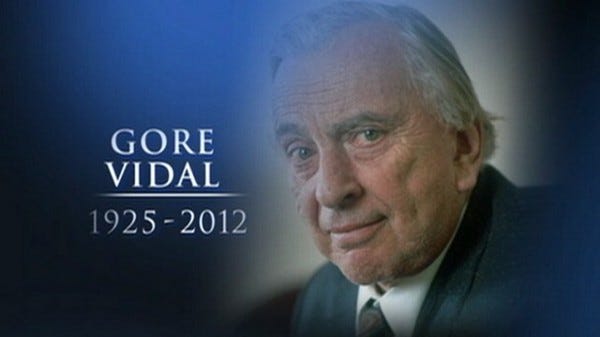

Gore Vidal died in 2012 at the age of 86.

He had written some 28 non-fiction and more than 30 novels across his lifespan, along with a significant number of plays for screen and theatre.

Three years before his death he publicly and repeatedly warned that America was heading towards a dictatorship.

The Times reported:

America has “no intellectual class” and is “rotting away at a funereal pace. We’ll have a military dictatorship fairly soon, on the basis that nobody else can hold everything together.

"Don’t ever make the mistake with people like me thinking we are looking for heroes. There aren’t any and if there were, they would be killed immediately. I’m never surprised by bad behaviour. I expect it."

This piece is from John Stapleton's upcoming memoir of journalism Hunting the Famous.