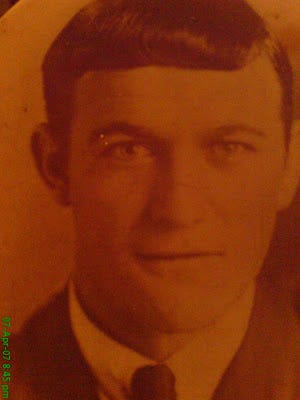

This is my grandfather John Henry Higginbottom. There are very few pictures of him around. He died a good 25 years ago. This generation was all a product of the depression. He was tiny, in the way of that generation. My clearest memory of him is when he used to visit when we were kids, at Wallamutta Road in Newport. In those days, before it became the trendy northern beaches and people flocked in their tens of thousands, it was an isloated place; beauitful in the richly coloured way of the Australian bush, koalas still common in the treetops, the light catching the feathers of an escaped budgerigar after it had been swooped on bny a kookaburra. To my memory; overlaid by many things, it had always been a nightmare against green; a violent, overbearing silence taunting the agony of adolescence.

Life in the city was jagged and confronting, but this is not where they came from. My father, in the airforce at the time, tilted the wings of his bomber towards their house on the hillside in Uki, a tiny village on the north coast of NSW. The neighbours complained of rattled crockery. Pop, as we called John Henry, was, by all the reports of his children, was alcoholic; and their stories of growing up were not just of poverty, but of all the problems that went with that, thrown dinners, fetching him out of the pub, hiding money, stolen pocket money, the difficulty of even getting pins for sowing.

The other side of the family had once owned land, before losing it in the depression, but this side was always deadpoor white.

"Let's face it, he was not a very nice man," said one of my uncles after his death. But I remember him as a kindly, older, little man, who much to our astonishment and fascination, would always be the first one up if he ever came to stay. We would find him on our verandah, the one that dad had built and looked down a steep valley of palm trees. My greatest triumph as a child was to set the entire valley alight, for once a fire got going in the tops of one, it would jump. No houses were burnt, but they were endangered, and I got into an enormous amount of trouble. Pop would be there, on the verandah, with his first beer of the day, sipping, sipping, having a quiet smoke. He liked to get a quiet one in before anyone got up to disturb him.

Even though they now lived in housing commission units at Narrabeen, not far from the beach, he grew tomatoes and beans in the small amount of dirt provided, and would always welcome you with the cosy tenderness of the bar. He was always gambling, smoking, drinking, just in a more subdued manner as he got older. One of his proudest moments was taking me to the public bar of the Antler, I think it was called, where he could introduce his grandson. Our grandmother, much to hers and everybody else's pride, got her car licence in her 60s, and he would sit in the driver's seat issuing an endless stream of instructions. Everyone regarded her as a saint, for more reasons than one.

Whatever his faults, he carried the kindness of the country and the rough camaraderie of the bar with him.