Fake news or no news? The folly of Australia's News Media Bargaining Code

Kim Wingerei: Michael West Media

Meta’s declaration that Facebook will no longer pay (some) Australian publishers for their news content has again highlighted the folly of the News Media Bargaining Code. It’s a poor solution to the wrong problem.

Facebook’s threat to jettison news puts the Government in a bind. If the Albanese Government decides to invoke the Code and force Facebook to the table, Meta may decide to do what it has already done in Canada and block news content on its platform. That will serve nobody, least of all smaller community outlets whose main mode of communicating with readers is a Facebook page.

And if the Government doesn’t, it emboldens Google when its agreements with media companies come up for renewal in a couple of years.

Another possible outcome is to revamp the Code or scrap it altogether and replace it with more effective regulation (a levy or a licensing regime, say), risking the loss of the revenue that Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, Nine Entertainment, and the other legacy media presently enjoy. Hell has no fury like Murdoch, Nine Chairman Costello and Stokes out West missing out on their ill-gotten freebies. It is not a palliative prospect for Labor a year or so out from an election.

Although the mess is the making of the LNP Government, it is now for Communications Minister Michelle Rowland and Assistant Treasurer Stephen Jones to resolve.

Revenue redistribution

According to IBISWorld – a market analysis firm, the digital advertising market in Australia is estimated to be worth $15.3bn in 2024. Of that, Google’s share is $8.9B – 58.1%, and Facebook 2.7B – 17.6%. The rest battle over the 24.3% that’s left.

The Code was meant to help Australian media companies “level the power imbalance” between the social media and search behemoths and “support quality journalism.” The only thing it has achieved is redirecting around. 2.5% ($300M) of Facebook’s and Google’s advertising revenue to another global behemoth, News Corp, plus to Australia’s largest media companies and a few smaller ones.

And in the process, it has further reduced the tax paid in Australia by Meta and Google from very little to a mere pittance.

It has also done very little to promote quality journalism. The ABC is the only recipient of this redistribution that has stated the money is used to employ more journalists. The money goes straight to revenue, can be spent on anything, and effectively subsidises a last-century industry.

Social media vs search engines

The Code treats all of the so-called Digital Media Platforms (DMPs) the same: Facebook, Twitter, and other social media on the one hand and Google, a search engine on the other.

The social media platforms are all based on users and content providers posting on their sites. Their algorithms are designed to maximise advertising revenue by serving up the ‘right’ posts to the ‘right’ users. The only interaction with the content providers is linking back to their sites. To their benefit.

But they are not the same.

Google, in contrast to Facebook, trawls every bit of content it finds, curates and rates it for its search engine and inserts ads to maximise its advertising revenue.

Both are useful services that consumers want. They offer their utility for free in return for users giving them their data, including their behaviours and preferences. Both are very good at what they do and demonstrably better at maximising their advertising revenue than ‘traditional’ media companies.

Yet, the Code does not differentiate between their very different functions.

Nor does the code do anything to address the real distortion of news and commentary dissemination of the platforms.

It does nothing to reduce misinformation, it doesn’t compel them to moderate or filter questionable content, such as fake news, hate speech and predatory exploitation of children and other vulnerable users.

It also does nothing to stop these companies from selling their data or stop that treasure trove of data from being used for surveillance or other nefarious purposes.

The Facebook conundrum

It is worth repeating that the Code was designed – following heavy-duty lobbying by Murdoch and Nine media – as a threat to ‘force’ Facebook and Google to negotiate, which they did. The Code’s key mechanism is to ‘declare’ a Digital Media Platform (DMP) and thus make such negotiations mandatory, with the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) having the power to appoint an arbitrator as a last resort. None of that has happened; the Code has remained a threat, but no DMP has yet been declared under the Code.

Such an outcome would trigger a visible, bureaucratic process, and open the claims up to other media – something neither the old media nor new media counterparties wanted. And it is a slippery slope; would Elon Musk’s X, or TikTok and Reddit be dragged in; and would all the platforms then come under pressure in other countries to pay?

Facebook owner Meta was a reluctant ‘participant’ when the Code was first introduced in 2021. It threatened to remove News altogether – and even did block news for a few days – but eventually caved in under pressure, doing deals that reportedly pay $70M annually to 13 media companies. The lion’s share of that money goes to News Corp, Nine Entertainment, Seven Media, the ABC and The Guardian.

At the time, Facebook did have a news pages section, which it has now abandoned. This is their argument for not paying for the news posts that news companies (and users) voluntarily place on the platform. Facebook claims this traffic is only 3% of its total content.

It has made it clear to the Government that if it were to force them to pay by declaring them under the Code, it would simply block all news content on its site. Or it might take the Government to court. That’d be ‘fun’, especially for the lawyers, having to fund an expensive lawsuit to protect Rupert Murdoch’s revenues.

The Canadian experience

The Canadian ‘Online News Act‘ was enacted in June 2023 and is quite similar in intent and scope to our News Media Bargaining Code. Both Google and Facebook initially rebelled against the act, threatening to withdraw news from their platforms. Google eventually relented and agreed to pay CAD100M ($112M) annually to a fund managed by the media industry.

Facebook stood by its threat and has blocked news on its platform in Canada.

The ban has been devastating for some. Not the major news outlets, though, but mainly for regional and niche news media companies. According to an article in Voice of America (VOA), a global independent news service, “small local news outlets that relied heavily on Facebook to attract audiences to their own websites say they are suffering”. Many claim to have lost significant chunks of their audience, including their print audience in some cases.

(It is worth noting that Canada is blessed by the absence of any Murdoch-run media companies.)

And it’s not just news coverage that has suffered. “One of the most immediate impacts of the Facebook ban came during record wildfires that raged across much of Canada last summer, just weeks after the Facebook action commenced.”

Residents found themselves unable to turn to the social media platform for the latest news on the spread of the fires and potential rescue efforts.

Google-power

Google – less reluctantly – entered into agreements with 12 out of the same 13 media companies that Facebook did a deal with, plus another 14 smaller and niche-oriented publishers. The annual value of these payments is believed to be between $150 to $250 million a year. The agreements are all confidential. (For the record, MWM decided not to put our hands out for Google or Facebook money.)

Google also played its hand quite cleverly by shuffling the news content it pays for into its ‘News Showcase’, an area that few people visit. It’s 0.4% of their global traffic in February 2024, according to SimilarWeb – a web analytics company. It doesn’t impact their algorithms and, thus, not their advertising revenue.

However, another oft-forgotten reason Google decided to ‘play ball’ is fear of having to divulge some of its innermost secrets.

Section 52S of the Code has a provision for Google to announce changes to its algorithm with fair warning to the media companies.

Even if ‘declared’, Google will no doubt resist that at all costs. The global repercussions of having to reveal some of its innermost secrets may well be too much for the executives in California to contemplate.

Other solutions

Australian media regulations have not been fit for purpose for a very long time – if they ever were. Almost thirty years after the internet changed how news is distributed, found, and consumed, our laws have barely changed. As a result, we have some of the most concentrated traditional media ownership in the ‘free’ world while having no control over how ‘new media’ operates.

One somewhat piecemeal solution to the current quandary is to add a ‘must-carry’ provision to the Code. Will Hayward, CEO of Private Media, suggests that if Facebook does block news content, the Code could be updated to force them (and the other platforms) to carry news.

However, that still begs the question of why Facebook should pay for content placed on its platform by users and news companies. It also doesn’t solve the fundamental problem of the Code, a piece of legislation designed as a flimsy hammer with scant regard for the size of the nail or where it goes.

Another solution floated is to make the global behemoths pay a levy and use the proceeds to subsidise and facilitate media diversity. But if so, what determines who pays the levy? How much should Peter pay Paul, and why should Rupert not pay?

Licensing is another option. To broadcast TV and radio in Australia, you need a license. With that license comes responsibilities and accountability.

Why not consider a licensing regime for social media platforms, search engines and all the other different means of distributing content to users not yet invented?

A license should be freely granted to those who comply and pay a license fee – as well as tax on all profit earned in Australia. It would also enable legislation that compelled the licensees to manage and control their content based on criteria set by the Government, not by people in Menlo Park or Mountainview, California.

Moreover, it is not the Government’s role to pick winners but to facilitate a controlled marketplace that benefits as many of us as possible.

Picking winners and losers?

Online media companies – including this masthead – benefit immensely from both Facebook and Google. Relevant quality content does ‘score’ better in search results, a point often conveniently ignored by those sharing the current spoils from Google and Facebook.

However, the global DMPs have immense sway over what content Australians share, read and don’t read; and an oligopoly level of dominance over online advertising revenue.

What about the other global social media platforms such as Telegram, WeChat, TikTok, Twitter, and – God forbid – Donald Trump’s Truth Social which may well come to Australia soon (and just announced a loss of more than $US58m on just $US4m million in revenue for 2023)? And let’s not forget that freedom fighter darling Reddit is now a public company and will soon have to find ways to monetise its 450 million users. And what about YouTube? And, and, and…

Google is also not the only search engine. It may enjoy over 90% share of search traffic overall, but Yahoo and Bing keep toiling away, as does nerd favourite and ad-free DuckDuckGo. In Russia, Yandex is much bigger than Google, with a 71% share, and Baidu dominates in China. Google will not dominate forever, and we are just seeing the very early days of the AI revolution.

The News Media Bargaining Code is a very poor solution whose singular effect was to squeeze some dollars out of a few companies to the benefit of (mostly) Australian mainstream media companies.

Kim Wingerei is a businessman turned writer and commentator. He is passionate about free speech, human rights, democracy and the politics of change. Originally from Norway, Kim has lived in Australia for 30 years. Author of ‘Why Democracy is Broken – A Blueprint for Change’.

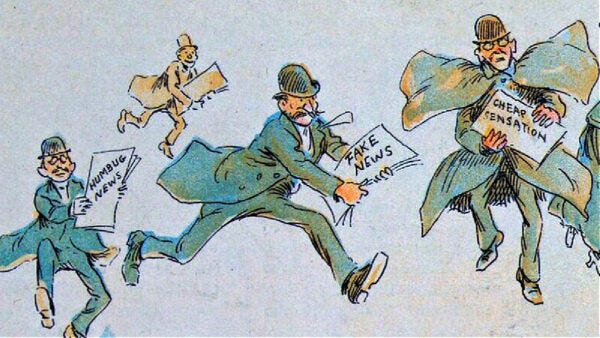

Feature Image: Image Frederick Burr Opper (1894). Courtesy of Wikipedia.