Death of the Darkroom, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 June, 1994. Pic Greg White.

One of the last stories for the SMH before moving to The Australian.

DEATH OF THE DARKROOM

Author: JOHN STAPLETON

Date: 05/06/1994

Words: 828

Publication: Sydney Morning Herald

Section: Computers

Page: 48

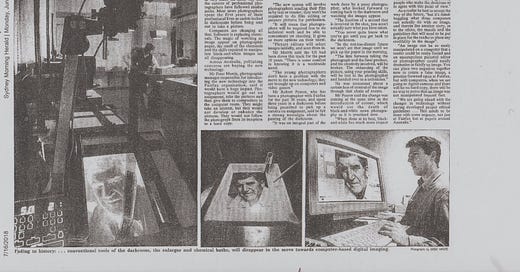

WE are living through the final days of the darkroom. For much of this century photography has been conducted in very much the same way and the careers of professional photographers have followed similar paths. Most news photographers spent the first years of their professional lives as cadets locked in darkrooms before being sent out to take a picture.

Computers are changing all that. Software is replacing chemicals. The magic of watching an image appear on photographic paper, the smell of the chemicals and the skills required to manipulate black-and-white images are all disappearing.

Across Australia, publishing concerns are buying the new technology.

Mr Peter Morris, photographic manager responsible for introducing the new technology into the Fairfax organisation, said it would have a huge impact. Photographers would go out on assignment, take the pictures and then give them to compositors in the computer room. They might take an interest, but they would not develop or enhance the pictures. They would not follow the photograph from its inception to a hard copy.

"The new system will involve photographers sending their film in by taxi or courier; they won't be required to do film editing or prepare pictures for publication.

"It will mean that photographers will be required less to do technical work and be able to concentrate on shooting. It gives us more options on their talent.

"Picture editors will select images initially, and scan them in.

Mr Morris said the US had been down this track for the past 10 years. "There is some comfort in knowing it is a worldwide trend.

"The young photographers don't have a problem with the move to the new technology; they are brought up on computers and video games."

Mr Robert Pearce, who has been a photographer with Fairfax for the past 30 years, and spent three years in a darkroom before being permitted to pick up a camera on assignment, said he felt a strong nostalgia about the passing of the darkroom.

"It was an integral part of the work done by a press photographer, who looked forward to coming back to the darkroom and watching the images appear.

"The fraction of a second that is involved in the shot, you aren't actually sure what you have taken.

"You never quite know what you've got until you get back to the darkroom.

"In the not-too-distant future we won't see that image until we pick up the paper in the morning.

"The link between taking the photograph and the final product, and the creativity involved, will be broken. The enhancing of the picture, using your printing skills, will be lost to the photographer and handed over to a technician."

He was concerned about a certain loss of control of the image through that chain of events.

Mr Pearce said the change was coming at the same time as the introduction of colour, which would see the death of black-and-white news photography as it is practised now.

"When done at its best, black- and-white has much more impact than colour news pictures. I see room for black-and-white news photography to remain and if the advertising people want to go the colour road, I see the one contrasting the other, not colour taking over totally. Unfortunately I have not been able to get many people who make the decisions to to agree with this point of view."

As a realist he had to accept the way of the future, "but it's mind-boggling what these computers can actually do with an image, and therein lies another story, as to the ethics, the morals and the guidelines that will need to be put in place for the reader to place any credibility in the image".

"An image can be so easily manipulated on a computer that a reader could be easily fooled and an unscrupulous pictorial editor or photographer could easily dramatise or falsify an image. You can place two negatives together now to create a false image, a practice frowned upon at Fairfax, but with computers, when we are going to digital cameras and there will be no hard copy, there will be no way to prove that an image was not manipulated beyond fact.

"We are going ahead with the changes in technology without having developed proper ethical guidelines ... This needs to be done with some urgency, not just at Fairfax but at papers around Australia."