Covid Line

By Jeremy Aitken

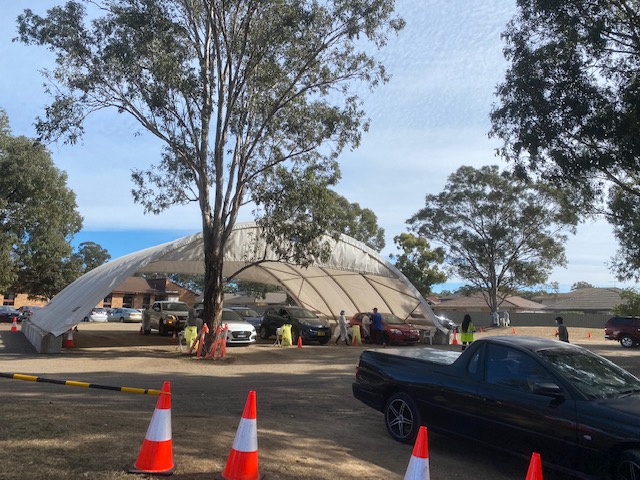

It is 7.00am Wednesday morning in early Spring. It is hot under an almost transparent clear blue sky; the tarmac is already starting to radiate heat and is steadily becoming hotter. A large white marquee has been set up in a suburban commuter train carpark, in it a police wagon with two young detectives is waiting. The detective on the driver’s side is filming his mate. A student nurse, dressed in full personal protective equipment (PPE), walks up to the passenger and slides a thin white swab stick into his nostril, deep, looks at the detective in the driver’s side, smiles and twists the swab around. The police officer is connected to the nurse like an umbilical cord. She pulls the swab stick out, places the sample in the vial, as the testers start to cheer, I clap.

The constable who has been tested has both his hands on his forehead as tears roll from his wet red eyes down his cheeks, a common response from the swab.

The detective in the driver’s side smiles, waves to the nurse, and drives off into the day. It is going to be a great day!

We are deep in lockdown and the new mandatory requirements mean that essential workers must test every three days. Today will see between three to four thousand tests being done. Heat is beginning to rise from the tarmac and is mixing with car fumes and as the sun reflects off the car windows it’s really hard to see and write the patient's details on the vials.

I am a first-year undergrad nursing student on a two-week mid-semester part time job, which was advertised via an email to our nursing student inbox: "Wanted Covid testers, training provided, multiple positions and locations through-out Sydney."

I was assigned to the drive through centre in Leumeah, a suburb in a Local Government Area (LGA) of concern in the southwest of Sydney. I had printed my NSW Government essential worker permit to enable me to enter the LGA, had my final vape.

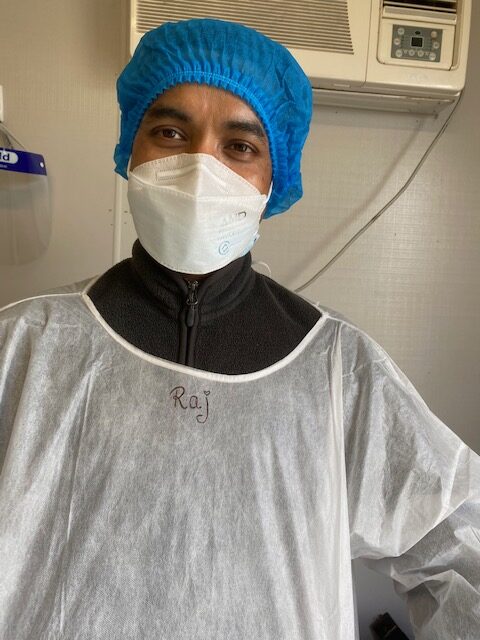

In the staffroom I suited up in personal protective equipment (PPE). There were two other new starters for the 7.30am shift, a young male nursing student in first year at suburban TAFE and a young female student nurse from North Shore College.

A young Nepalese man called Diep, a fast talking, efficient tester who had been working at Leumeah for two weeks trained me. He asked me my name but settled on "brother".

Diep demonstrated how to swab and collect samples. We wait for the next car to drive up to our station. It’s finally my time. The window is lowered.

Hi, how are you today? Are you a close contact? Ok, yep, I guess no one knows, haha. You been tested before? Yes, sorry, every three days is annoying. I’m just going to take a swap from either side of the back of your mouth and then your nose. Could you please face me and say ahhhh.? Sorry, throat is done. Nose now, yes, I’ll be careful, sorry, other nostril. I understand you have a broken septum; I’ll be careful, sorry. Yes, thank you have a good day.

The car window is raised, we wave, and they drive off. I will say the above script or variations of it an average of 30 times an hour for the next 11 hours. That’s roughly 330 mouths and 660 nostril cavities over 11 hours.

A nurse who has accessorised her scrubs with cool black shoes with gold lightning bolts on them comes over and looks at my forehead.

'Hi, you, ok?' she says, 'Give your visor to me.'

She peels off a protective film on the visor, gives it back and smiles.

'There, much better.'

I’m embarrassed but at the same time impressed at how my sight has improved I say ‘cool’ and look around seeing the marquee clearly. Her name tag says Corrine. The next car comes through.

'Please be gentle, it’s my first test,' says the driver.

'Well then we have to make sure we get some brain and blood and snot on that sample stick,' says Corrine.

The driver doesn’t know quite what to make of it as I take the sample as gently as I can.

Corrine looks at the swab and isn’t impressed.

'Next time,' she says. A chilled-out client drives out.

'That was cool,' I say. 'Where’d you learn that?' I say.

'What?'

'How to calm stressed out people?'

'Aren’t you a nurse?' says Corrine. 'No trick, always have fun and hilarious shit happens.'

I nodded to her and gave the thumbs up.

'Yeah!' she said. As she walked off, she said Woop, whoop!

I loosen up after that. Diep nods impressed by how quickly I have picked it up and moves to another workstation. I think he heard me say thanks and I’m struck by how much I rely on facial expressions to work out if people are friendly.

A car comes and I lean in and record the details on the vial and then ask,

'Close contact, anything I should know?' I say.

‘Yes, my husband,’ she says.

‘When?’

‘Yesterday,’ she says.

I step as far away from the car as I can and take the swab, call over a nurse who tells me to write Urgent, Close Contact on the vial. The driver is worried and asks the nurse what she should do. The nurse tells her to go home and isolate. I then ask the nurse what I should do.

'Nothing, you’ve probably had a few close contacts already. Keep your PPE gear really secure, no gaps and if in doubt sanitize.' she says.

I start to imagine that there are small cuts in the PPE gear and that delta Covid is mixing with the fumes and heat. I start to rub alcohol on my gloves, it comes in two colours pink and white, I choose pink and for the next while I double glove.

A young dude about 21 came through with symptoms of Covid; diarrhoea and vomiting. He’d been having a few cans the night before and got some home delivery via contactless delivery, but the dude hadn’t washed his hands after getting his meal from the front door: he was paranoid. Thanks for making my morning and I’m sorry if I laughed but that was great. I’m sure the test came back negative, and I hope that by writing urgent on the vial calmed him a bit.

A car comes in with a young police officer who informs me that he has had close contact. He was involved in an arrest last night and the suspect was Covid positive. It was his second test, his first being one he had at the Police Academy last year. He was nervous so I told him to stay safe as I wrote ‘urgent police close contact’ on his vial.

I’m sore and needed to go to the toilet. It’s hot, I am beginning to dehydrate, the car fumes are annoying me, it’s hard to write on the vials, I’m uncomfortable. My pants are falling, my mask needs adjusting, I can’t touch anything, and the cars keep coming. The sun has risen high in a clear blue sky and is starting to spill into the marquee and hit my feet and legs. It’s very disconcerting being cooked in plastic and not being able to move or adjust clothing.

The nurse in charge of the morning shift, Teressa, came to check on me. She stood and looked at me for a moment. I felt as though I was undergoing a health check.

'Your face mask will cut into your ears if you wear it like that.' she says.

She got me to readjust me mask, so the straps were on the top of my head and not on my ears.

'Thanks,' I say.

'We all have to look after each other here,' she said.

I decide then to see if I can stay at this centre for the rest of the holidays.

There were things that annoyed me which I never thought would. I would kill for boxes of extra-large gloves, sharpie pens that work, the length of time the bright light stays on a mobile phone before dimming, and people with multiple nose piercing who ask me to negotiate their crusted crevices with care. Also, excessively hairy nostrils, they are really hard to stick swabs through and think it is your fault. People who lower their seats and look at the roof of the car. People who can close their nostrils at will, both amazing and spooky.

Covid testers universally say their number one complaint is, big guys who absolutely baulk at having the test.

'I’d prefer to get six hours of tattooing than have that done.' They all say. Overall, they leave with teary eyes – stay still!

Oh, and nurses do judge you on how well you take the test, even if they say 'don’t worry' you’ve been judged.

'I’m nervous,' say many people.

'Is there any way you can get a sample without going in my nostrils? I have hay fever/polyps/broken it/done too much cocaine,’ say even more.

‘Well, I can go rectally, I get a much better swab.’ I say.

(I normally flick my rubber gloves and look at the swab stick at this point)

'Your choice,' I say. No one called my bluff.

I’ve swabbed old people, young, babies, lots of babies, people drinking beer, people smoking and vaping, people who have just eaten and lots that are chewing gum and stick it on the roof of their mouths with their tongues and then say sorry. And I’ve heaps of different coloured tongues from energy drinks.

‘This is my good nostril,’ say many.

I’m always impressed that people know which one is the best. People sneeze, their eyes will water, and they will be relieved to go. That is the rhythm of the day.

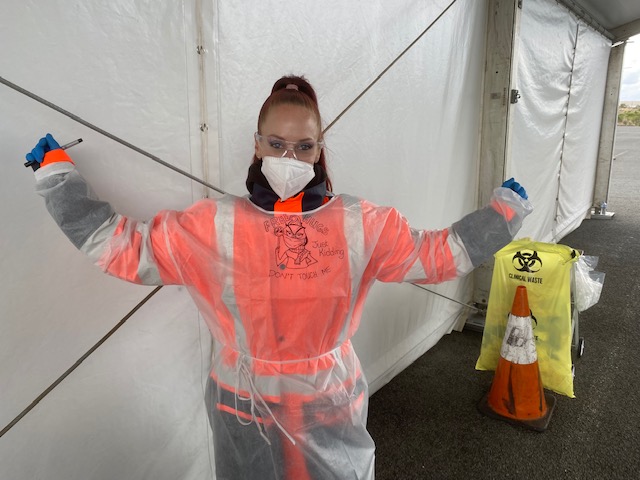

Three young women dressed in steel cap boots, blue fitted overalls, fluorescent jackets that say ‘Traffic Controllers’ dart in and out of the moving traffic, directing it. Their long hair is pulled back under helmets, on top they wear protective gear and its hot, plastic face shields, gloves and they move constantly under the direct sun, up and down lines of cars, directing, handing out information on how to generate Covid testing numbers.

A taxi with a family of Afghani refugees drives in and Kerry, one of the traffic controllers, hops into the taxi to get their passports and fills in the vials for them.

'Man, did you see their eyes?' Kerry said. 'Green and blue, amazing looking eyes, man. Beautiful.'

In the middle of the tent are a few young nurses to whom Diep says 'Hey, the sun is not as beautiful as you are.' And they all laugh.

My back is shot, and I jump to try and pull my sagging pants back up. I’m playing cool as no one else seems to be suffering and they take the work super casually. Lunch comes at 12.30 when a nurse, again I’m not sure who, it might have been Minnie or Rasta or Rim, said I could take a 30-minute break.

About 50 millilitres of sweat pours from my PPE jacket, my shirt is sticking to me and I’m sure I’ve lost weight. I talk to Kerry, who runs the traffic control and asked her how they do it.

'You do what you got to do,' she said.

'You get used to it,' said Breeze, another traffic controller. 'Besides, I'm mostly here to socialise. I'm making the most of being free! Lockdown sucks!'

They had little sympathy for anyone as they started work at 4.30am and will finish at 6.30pm; they had been doing it for months. I asked Kerry what her biggest problem was

'Whinging men who don’t like being swabbed, seriously, get over it. I say to them Bunnings is over there, drop in on the way home get a bag of concrete and harden the fuck up!' she said.

She has a cartoon of a chicken drawn on her PPE equipment that says, Free Hugs, not really free.

In the staff room where two other women were sitting, both Nepalese nursing students and Diep. This time they were unmasked, and I could see that Diep had a goatee with a bit of grey in it so he must have been around 35 years old. He was a chef and had worked all around the world, mainly working on cruise ships, but during the last few years he’d be working at the Bavarian cafés in Sydney and Melbourne when covid hit, he had no work.

He then asked me if I liked cars and showed me his phone with his Audi TT as his screen saver.

"This is my dream car, brother. I love this car from the time I was in Kuwait. Now I can smash money off it,' he said. I was super jealous.

The women were in their early 20s.

They worked 7 days a week for 11 hours a day. They could pay off a credit card bill in a month. Most of the testers were undergraduate nursing students, some were working as individual support workers and had worked in aged care but for the past two months everyone had been working full time on the covid lines around Sydney. It paid better, than aged care because the shifts were longer, and they didn’t get yelled at by patients.

They shared stories, Leumeah was one of the best testing centre as they had two regular breaks, you don’t need permission from the supervisor for a toilet break, 30 minutes for lunch and it was only 11-hour shifts. International airport was the worst, no breaks, toilet is supervised and only a 30-minute lunch break.

'You have more chance of dying from heat exhaustion than Covid.' said a young student nurse and the others nodded.

They were more interested in me. 'Why was I doing this? Was I married? Did I have children? Why not? Would I get married again? No others old guys did this. Why?' They seemed to think that I wouldn’t be around tomorrow, they’d seen this before.

I met two first year domestic nursing students, one from UWS and one from Macquarie who were doing the rounds of the covid testing centres. Leumeah was fun, Minchinbury is an open field, and you get super muddy when it rains. One of the women showed me her shoes, I got a picture of the three of us in PPE. Frenches Forest was where they were headed next; they are hilarious, and I hope they found their Shangri-la.

I was placed in a workstation with a young student nurse from Myanmar who came to Australia with her family in 2011. She lived in Bankstown and was worried about the late shift because her mother didn’t like her driving in the dark.

From 2pm onward I was dehydrated and hot at the same time. I pushed the PPE plastic on my arms, it stuck to my skin and felt weird, sticky cold clammy. It was disconcerting being able to see your breath condensing on the visor, and everything look smudged and to not be able to touch your face and adjust your mask knowing that a simple move of the mask would make your life so much easier.

Then it was over, the gates close and the last cars drive out. Diep shows me the correct way of removing my PPE gear, rip it off and throw it in a single triumphant move into the industrial waste bin. The relief from taking off the elastic hairnet, visor and face mask was so sweet release that it was almost worth the discomfort.

A couple of cool moments that made my day. A heavily tattooed guy in a red Ute with Souths and Rabbitohs all over it came in and was super cool thanking us for all our hard work. He respect knuckled us, told us to stay safe. Go Souths!

To the people of Leumeah and Campbelltown, thank you for being so friendly to me while I scraped your throats. Thank you for wishing me well when your eyes were red, and tears ran down your cheeks. To the nurses, traffic controllers and testers of Leumeah, you rule! Thanks so much.

Heaps of people wished me well and told me to stay safe – to you all thanks! After 14 Covid tests and 10 rapid pathogen tests, I am still negative.

Jeremy Aitken is a Sydney-based writer, former UNSW Global English lecturer, and now first-year nursing student at the University of Western Sydney.

He is also the author of the novel Crystal Street and in 2006 was Highly Commended in the Australian/Vogel for his manuscript, ‘The Bike’, a semi-autobiographical novel.

His piece for A Sense of Place Magazine ‘The Covid Line,’ is based on his part time job as a front line COVID tester seeing the full colourful array of humanity as they react to having a stick shoved up their nose and the working conditions of 12 hour days in all kinds of weather.