Coercive Control: Imprisoned by Language

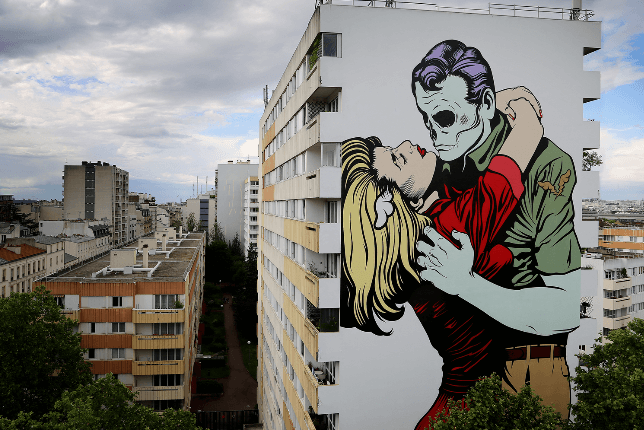

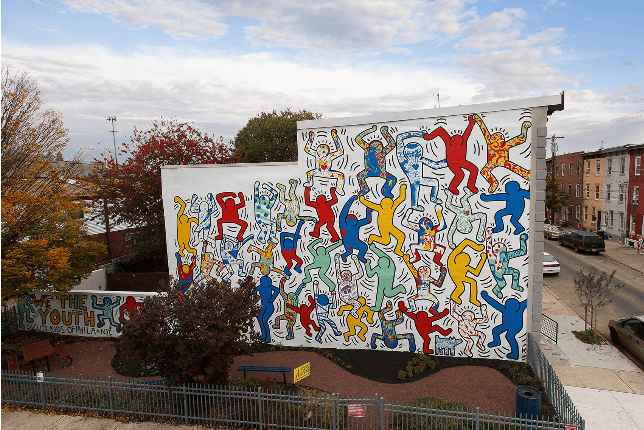

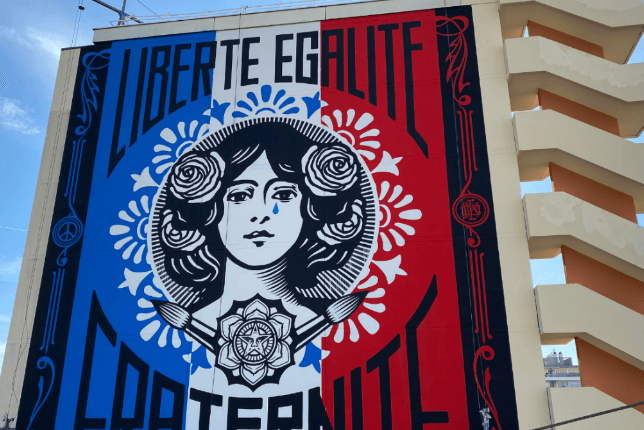

By Sue Price: Men’s Rights Agency. Illustrations from Artsper Magazine’s piece on The World’s Most Famous Street Art.

Coercive Control: When this terminology first came into focus as the next label women were seeking to use to expand the meaning of domestic/family violence, we saw, as expected a plethora of conferences, reports and talkfests supporting the notion that women were indeed subjected to a multitude of situations that could be compiled under the term Coercive Control to provide a more impactful accusation for use in domestic/family violence applications. In fact, to become a criminal offence.

Coercive control is describe by the United Kingdom’s Crown Prosecution Service as:

Monitoring activities: A person may exert control by deciding what someone wears, where they go, who they socialize with, what they eat and drink, and what activities they take part in. The controlling person may also demand or gain access to the partner’s computer, cell phone, or email account.

The perpetrator may also try to convince their partner that they want to check up on them because they love them. However, this behaviour is not part of a healthy or loving relationship.

Exerting financial control: This occurs when a person controls someone’s access to money and does not allow them to make financial decisions. This can leave a person without food or clothing and make it harder for them to leave the relationship.

Isolating the other person: A controlling person may try to get their partner to cut contact with family and friends so that they are easier to control.

They may also prevent them from going to work or school.

Insulting the other person: Insults serve to undermine a person’s self-esteem. This may involve name-calling, highlighting a person’s insecurities, or putting them down.

Eventually, the person experiencing this abuse may start to feel as though they deserve the insults.

Making threats and being intimidating: Threats can include threats of physical violence, self-harm, or public humiliation. For example, a person trying to control their partner may threaten to hurt themselves if their partner tries to leave or release sexually explicit images or personal data online.

The controlling person may also break household items or their partner’s sentimental belongings in an attempt to intimidate and scare them.

Using sexual coercion: Sexual coercion occurs when the perpetrator manipulates their partner into unwanted sexual activity. They may use pressure, threats, guilt-tripping, lies, or other trickery to coerce them into having sex.

Involving children or pets The controlling person may use children or family pets as another means of controlling their partner. They may do this by threatening the children or pets, or by trying to take sole custody of them if their partner leaves.

They may also try to manipulate children into disliking the other parent: All of the above sounds to be well within the capabilities of women, who may not have the physical strength to lash out but, can over a period of time, destroy their partner’s life with severe criticism in front of relatives and friends; denigration of their partner’s ability to earn a living and provide for the family; repeated accusations of “you’re useless, pathetic, not a man, a useless lover”.

Continuous assault on a person’s psyche can indeed cause deep depression and PTSD. Perhaps that’s why we have so many men taking their own lives. Statistics tell us 85% of suicides could be as a result of relationship breakdown.

The last category mentioned is important recognition of the most damaging abuse a father can experience. To manipulate children into disliking the other parent is devastating for the father and the child. They are brainwashed to accept their mother’s view that the father does not love them, doesn’t want to see them.

If she cannot succeed in alienating the children from their Dad she can always encourage accusations that he has interfered with the children or raped her.

Most children are well aware they are the product of both a mother and a father. If the mother displays her hatred of the father to such an extent the children will wonder which part of them does the mother hate and dislike. How many times have they been told, “You’re just like your father”, when Mum berates them for some minor transgression.

False allegations are rife in family separation!

A number of years ago, my view that most false allegations, especially in domestic/family violence allegations are made to gain an advantage in future family law applications for custody and property settlement was confirmed in media interviews and research. For example:

In 1991, Supreme Court Justice Terence Higgins, when overturning a Canberra woman’s domestic violence protection order against her estranged husband, described “as nonsense the woman’s assertions that the statements attributed to the man had represented a threat to her safety” and he further said “the woman was a liar and that she and her sister have fabricated their allegations”. Justice Higgins pointed out that “harassing or offensive behaviour could justify an order if the spouse feared for her safety. But that fear had to be an objective one and a reasonable response to the situation. “Mere criticism, nagging, even unreasonable persistence cannot credibly be described as ‘violence”.

His Honour questioned the practice of the Magistrates Court “in issuing protection orders merely to prevent annoyance by one party to a domestic relationship of another” and suggested that in this case “it seems to me that the resources directed towards eradicating or at least controlling violence in our society are being sadly misdirected”.

He concluded the woman’s evidence was deliberately false and revealed a consistently vindictive attitude.

In 1995, Queensland’s Chief Stipendiary Magistrate Mr Stan Deer acknowledged the problem of domestic violence orders being misused when he stated “some women are using domestic violence orders to gain a better position in child custody cases”.

Estimates provided to this Agency at the time, by court staff/prosecutors suggested that only 5% of applications for domestic violence orders were legitimate in their claims.

In 1999, a survey conducted with 60 serving NSW magistrates, conducted by the Judicial Commission of NSW found that most (90 percent) believed domestic violence orders(AVOs) were used by applicants – often on the advice of a solicitor – as a tactic in Family Court proceedings to deprive their partners of access to their children.

A further study of Queensland Magistrates found three out of four who responded believed parents use domestic violence protection orders as a tactic in divorce and custody battles. Like their counterparts in NSW several Queensland Magistrates believed many women applied for domestic violence orders on the advice of their solicitors.

If the usual allegations of “I am scared of him”, “he yelled at me”, or any other unsubstantiated complaint fails to encourage the police to apply for a domestic violence order, increasing numbers resort to false claims of child abuse, child sexual abuse or even rape of themselves.

Ian Leavers, General President and CEO of the Queensland Police Union submitted to the Committee inquiring into a Family Law Amendment (Federal Family Violence Orders) Bill 2021 intended to give power to the Commonwealth Family courts to impose domestic violence orders wrote on 16 June 2021:

“The QPU does have some concerns with the use of State based domestic and family violence orders in some instances where it would appear the first occasion on which an application for such an order is made, is upon proceedings being commenced for family matters in the Federal jurisdiction. There seems to a perception that having a State based domestic and family violence order will benefit a party to federal litigation. The QPU is aware of a number of occasions where this practice has occurred against its own members.”

It is the QPU’s position that family protection orders should be the preferred manner of dealing with family and domestic violence where concurrent proceedings are on foot in the Federal or Family Court. The QPU holds this belief, because it would mean only one court would be dealing with the whole matter, thus reducing the need to concurrent proceedings in the State or Territory courts.

Secondly, such an approach would ensure State and Territory based schemes for protecting victims of family and domestic violence cannot be abused by parties seeking an advantage in their federal litigation.

To deal with the ever-increasing flood of allegations the Family Court of Australia has established the Magellan model for case management.

Operating in most Registries, case management is intended to provide coordination and bring together all the departments that may be involved, state police, family services, statutory child protection agencies, and juvenile courts. The appointed Independent Children’s Lawyer is charged with organising various investigations with police, child protection, medical personnel, psychologists, family report writers etc towards the completion of the Magellan Report readied for hearing.

An evaluation of the Family Court of Australia’s Magellan case-management model has been conducted by Dr Daryl J Higgins from the Australian Institute of Family Studies.

There are many interesting views expressed by judges, who are involved in the Magellan process, contained in the evaluation.

Here is an example of a Judge’s view of the likelihood of Magellan matters dealing with cases that, upon investigation by the statutory child protection department, do not have the abuse or ‘unacceptable risk’ confirmed:

“I have a sense that in the overwhelming majority of cases, abuse is not confirmed. And probably in not many cases is there found to be an unacceptable risk. I don’t have the stats, so it’s probably silly of me to quote stats, but I’m talking of probably upwards of 70 or 80% where the relationship with the father is restored.

Which, in itself is a worry if that is true. Why are so few being confirmed? Is it mum—usually—using it as a weapon to get dad out of the kid’s life? Is it mum misidentifying the signals and then not accepting professional advice as to what it might really mean? Is it that there has been abuse, but the proof is inadequate for there to be the findings?”

Unfortunately, most of the discussion in the Dr Higgins’ evaluation is around automatically suggesting that the father is the abuser. Little attention is paid to the abuse committed by mothers, boyfriends, step-fathers, other siblings, and especially step-siblings present with the increasing numbers of blended families.

However, the Magellan process appears to produce good outcomes for fathers and their children. Their relationship can be restored. The problems are: the delays for a matter to be heard and the enormous costs involved when the father is persuaded to employ solicitors and barristers as he needs to if he wants a good outcome. The mother is most likely to receive Legal Aid funding.

All this can stem from a domestic violence application and false allegations of inappropriate behaviour that the police find themselves needing to make a decision on without any satisfactory information or evidence. Often it become a “he said” “she said” argument. The pressure exerted on the police via state government policy and women’s domestic violence services is intense and few police are able to withstand the dogma of “always believe the woman”.

At the moment, in the USA, there is much discussion about coercive control in a redraft of the Violence Against Women Act. (VAWA). Senators Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), Joni Ernst (R-Iowa), Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) drafted the VAWA bill expanding the definition of domestic violence to include “coercive control”, which they define as “behavior committed, enabled, or solicited to gain or maintain power and control over a victim, including verbal, psychological, economic, or technological abuse.

“The Center for Disease Control reveals that men are the primary victims of this type of abuse. Each year, 17.3 million men are victimized by coercive control, compared to 12.7 million females.”

Over the past 27 years we have been told of many occasions where an easily gained domestic violence order becomes the instrument of further abuse when a woman demands the partner completes certain jobs or responds to her demands.

Those demands could be “Stay away from our children; no you can’t come around to collect your clothes or personal items; no you cannot access our joint bank account for any of your money” or if he is still allowed at the house it could be “cut the grass, change the light globes, clean the house, or any one of a myriad of jobs demanding attention around a house… or else “I will call the police and report a breach of the domestic violence order”, which she has in her hand, waving it in front of the man’s face. That’s coercive control with a vengeance!

The American’s have named this coercion as the “honey-do lists”. The notion has become deeply embedded in American marriage culture. Not surprisingly, advice columns are filled with wry commentaries about honey-do lists that echo the “power and control” theme.

The only people who seem to be pushing for the introduction of “coercive control” are the women’s domestic violence groups.

Others such as Kate Fitzgibbon, a Senior Lecturer in Criminology at Monash University, Jude McCulloch, a Professor of Criminology also at Monash and Sandra Walklate from the Eleanor Rathbone Chair of Sociology, University of Liverpool disagree.

They recommend in The Conversation on November 27, 2017 that:

“Australia should be cautious about introducing laws on coercive control to

stem domestic violence.

More law is not the answer.

Recourse to the law remains one of the central planks of policy responses to intimate partner violence.

In the case of coercive control, our research suggests more law of this kind is

not the answer to improving those responses. We urge Australian jurisdictions

to be cautious about following in the footsteps of our English counterparts.

There may be a place for coercive control in law. But we believe a more effective role for this concept may lie in better-informed expert testimony presented to the court in the case of very serious offences.

Law reforms should be evidence-based and informed by an understanding of the problems the reform seeks to address. Policymakers must also look beyond the criminal law as a “quick fix” to a long-standing social problem and instead strengthen civil remedies, service access and delivery.”

In conclusion, I would have to suggest that rather than the introduction of coercive control being for the benefit of women it will in fact work against them as men come to realise they have been subjected to coercive control for many years.

Certainly, my advice to any man complaining of an ongoing tirade of abuse and denigration, is that he should apply for a domestic/family violence order citing coercive control.

Let’s see if the law works for both genders!

Sue Price, with her late husband Reg, founded the Men’s Rights Agency in 1995 after witnessing the terrible plight of the male employees in their retail business, many of whom were caught in the web of Australia’s utterly dysfunctional Child Support Agency and many others who were heart broken at the loss of contact with their children thanks to the abusive practices inherent in Australia’s family law.

While the Australian government pours billions into feminist advocacy, men caught in the nightmare web of false allegations and the shockingly dishonest practices that characterise family law receive nothing.

While members of the country’s tax payer funded femocracy congratulate each other on their courage, it takes genuine courage to run against the tide.

If anyone deserves an Order of Australia for her selfless dedication to the welfare of others and for her ceaseless efforts to bring fairness, decency and reason into family law and child support issues such as male suicide it is Sue Price.

Feature image: Banksy, The Little Girl with the Balloon, 2002 – London. Source: Dominic Robinson.

Read Artsper Magazine’s original piece The 10 Most Famous Pieces of Street Art in the World.