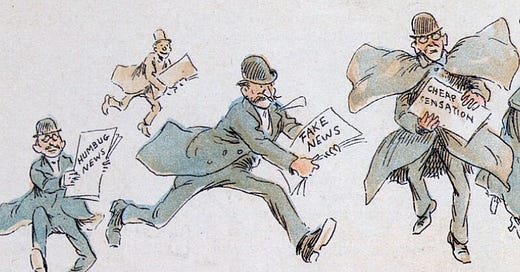

Censors Enthroned: Australia's Misinformation and Disinformation Bill. The Sirens should be going off.

By Binoy Kampmark: Michael West Media

Should the government decide what news is appropriate and what is not for its people?

The heralded arrival of the Internet caused flutters of enthusiasm, streaks of heart-felt hope. Unregulated, and supposedly all powerful, an information medium never before seen on such scale could be used to liberate mind and spirit. With almost disconcerting reliability, humankind would coddle and fawn over a technology which would as Langdon Winner writes, “bring universal wealth, enhanced freedom, revitalised politics, satisfying community, and personal fulfilment.”

Such high-street techno-utopianism was bound to have its day. The sceptics grumbled, the critiques flowed. Evgeny Morozov, in his relentlessly biting study The Net Delusion, warned of the misguided nature of the “excessive optimism and empty McKinsey-speak” of cyber-utopianism and the ostensibly democratising properties of the Internet. Governments, whatever their ideological mix, gave the same bark of suspicion.

In Australia, we see the tech-utopians being butchered, metaphorically speaking, on our doorstep. Of concern here is the Communications Legislation Amendment (Combating Misinformation and Disinformation) Bill 2023. This nasty progeny arises from the 2019 Digital Platforms Inquiry conducted by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

The final report notes how consumers accessing news placed on digital platforms “potentially risk exposure to unreliable news through ‘filter bubbles’ and the spread of disinformation, malinformation and misinformation (‘fake news’) online.” And what of television? Radio? Community bulletin boards? The mind shrinks in anticipation.

In this state of knee-jerk control and paternal suspicion, the Commonwealth pressed digital platforms conducting business in Australia to develop a voluntary code of practice to address disinformation and the quality of news.

ACMA empowered

The Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation was launched on February 22, 2021 by the Digital Industry Group Inc. Eight digital platforms adopted the code, including Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Twitter. The acquiescence from the digital giants did little in terms of satisfying the wishes of the Morrison government.

The Minister of Communications at the time, Paul Fletcher, duly announced that new laws would be drafted to arm the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) with the means “to combat online misinformation and disinformation.” He noted an ACMA report highlighting that “disinformation and misinformation are significant and ongoing issues.”

The resulting Bill proposes to make various functional amendments to the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 (Cth) as to the way digital platform services work. It also proposes to vest the ACMA with powers to target misinformation and disinformation.

Digital platforms not in compliance with the directions of the ACMA risk facing hefty penalties, though the regulator will not have the power to request the removal of specific content from the digital platform services.

In its current form, the proposed instrument defines misinformation as “online content that is false, misleading or deceptive, that is shared or created without an intent to deceive but can cause and contribute to serious harm.” Disinformation is regarded as “misinformation that is intentionally disseminated with the intent to deceive or cause serious harm.”

Who decides what’s harmful?

Of concern regarding the Bill is the scope of the proposed ACMA powers regarding material it designates as “harmful online misinformation and disinformation”. Digital platforms will be required to impose codes of conduct to enforce the interpretations made by the ACMA. The regulator can even “create and enforce an industry standard” (this standard is unworkably opaque, and again begs the question of how that can be defined) and register them.

Those in breach will be liable for up to $7.8 million or 5% of global turnover for corporations. Individuals can be liable for fines up to $1.38 million.

A central notion in the proposal is that the information in question must be “reasonably likely […] to cause or contribute serious harm”. Examples of this hopelessly rubbery concept are provided in the Guidance Note to the Bill. These include hatred targeting a group based on ethnicity, nationality, race, gender, sexual orientation, age, religion or physical or mental disability.

It can also include disruption to public order or society. The example provided in the guidance suggests typical government paranoia about how the unruly, irascible populace might be incited: “Misinformation that encouraged or caused people to vandalise critical communications infrastructure.”

The proposed law will potentially enthrone the ACMA as an interventionist overseer of digital content. In doing so, it can decide what and which entity can be exempted from alleged misinformation practices. For instance, “excluded content for misinformation purposes” can be anything touching on entertainment, parody or satire, provided it is done in good faith.

What is a ‘professional news provider’?

Professional news content is also excluded, but any number of news or critical sources may fall foul of the provisions, given the multiple, exacting codes the “news source” must abide by. The sense of that discretion is woefully wide.

chilling self-censorship it will inevitably bring about

The submission from the Victorian Bar Association warns that “the Bill’s interference with the self-fulfilment of free expression will occur primarily by the chilling self-censorship it will inevitably bring about in the individual users of the relevant services (who may rationally wish to avoid any risk of being labelled a purveyor of misinformation or disinformation).”

The VBA also wonders if such a bill is even warranted, given that the problem has been “effectively responded to by voluntary actions taken by the most important actors in this space.”

Rage of the Right

Also critical, if less focused, is the stream of industrial rage coming from the Coalition benches and the corridors of Sky News. Shadow Communications Minister David Coleman called the draft “a very bad bill” giving the ACMA “extraordinary powers. It would lead to digital companies self-censoring the legitimately held views of Australians to avoid the risk of massive fines.”

Sky News has even deigned to use the term “Orwellian”.

Misinformation, squawked Coleman, was defined so broadly as to potentially “capture many statements made by Australians in the context of political debate.” Content from journalists “on their personal digital platforms” risked being removed as crudely mislabelled misinformation. This was fascinating, u-turning stuff, given the enthusiasm the Coalition had shown in 2022 for a similar muzzling of information. Once in opposition, the mind reverses, leaving the mind to breathe.

The proposed bill on assessing, parcelling and dictating information (mis-, dis-, mal-) is a nasty little experiment. When the state decides, through its agencies, to tell readers what is appropriate to read and what can be accessed, the sirens should be going off.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He currently lectures at RMIT University in Melbourne.

Feature Image: Image: Maxim Hopman, Unsplash.

Further Reading