Canberra’s man in Washington during ‘Trumpageddon’

By Graeme Dobell: Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

When an Australian jumps out of a taxi and prepares to make a dash across New York’s 5th Avenue, the habit of a lifetime is to look the wrong way for the traffic.

Australia drives on the left; America drives on the right. It’s a simple metaphor for the many different ways of looking and moving of the two nations.

Rushing for a late-night drink in the city that never sleeps, Australia’s ambassador to the US, Joe Hockey, stopped his taxi by Central Park and dashed across the avenue, checking in the Oz direction.

That ‘near-fatal error,’ Hockey observes, was ‘like so many who think they understand America’.

Luck and quick reactions spared the ambassador an obituary about a culture-clash smash on 5th Avenue. Thus, this month, Hockey could release Diplomatic, a memoir of his time as our man in Washington from January 2016 to January 2020.

He starts with the big truth that shapes the life of any Oz representative in Washington: history has ‘made America fundamentally different from us’.

‘Many demons,’ Hockey writes, lurk ‘in the American psyche’. And that’s where the discussion of ‘inherent differences’ ends. The Hockey emphasis is on the ‘long and friendly history’ between the US and Australia:

It’s a bit like a successful marriage: we like each other a lot, we are not identical and do not always agree; however, we have shared our lives over many years. We are loyal to each other and we really enjoy each other’s company.

Hear the voice of the happy warrior who is Joe Hockey. Even after 19 years as a federal MP, culminating as treasurer from 2013 to 2015, Hockey departed Canberra with few enemies. His broad smile served him well in politics as it did in diplomacy. In both games, half a deal usually beats a duel.

Hockey went to Washington because his dream to become prime minister was dead. His luck deserted him in the series of political car crashes that marked the Liberal Party death struggle between Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull.

The chapter headed ‘Goodbye, Canberra’ has a subhead reference to ‘politics at its worst’, and the smile dims as he lets fly: ‘Within our [Abbott] government, there were too many who were more focused on polls than policy. The sickness of populism afflicts the weak. That didn’t stop them from engaging in duplicity and deceit.’

Ah, politics is a treacherous trade played for the highest stakes. Who knew? Lucky only volunteers enter.

The happy warrior notes that for 17 of his 19 years in the pit he was fortunate to be in the front line (on the government or opposition front bench) and, despite the nastiness, he enjoyed it immensely.

From Washington, Hockey did most of his work with Canberra on a secure phone, talking to the prime minister, ministers and department heads. Others in Australia’s embassy wrote the ‘cables’ that are a central expression of the existence of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (acting as circulatory system and thinking process).

Hockey’s Canberra understandings (‘the sharpest knives always come from your own side’) explain that phone preference—‘given my past life as a politician, if I wrote any cables, I couldn’t rely on all the people reading them not to share them with the media’. A well-directed leak can sink you. As Hockey notes, Britain’s ambassador to the US had to resign in 2019 after a London leak of his cables claiming that President Donald Trump ‘radiates insecurity’ and describing the White House as ‘clumsy and inept’.

Hitting Washington at the start of 2016 for the final year of Barack Obama’s administration, Hockey witnessed the close but not familiar relationship between President Obama and Prime Minister Turnbull: ‘Both men had a healthy love of detailed intellectual discourse—especially their own. Like two history professors discussing dialectical materialism, their conversation was eye-watering but hardly warm.’

Then comes the chapter headed simply ‘Trumpageddon’. On the Hockey telling, he read the signs of the presidential campaign and started building bridges to Trump, while Canberra was in denial till the votes came in.

Hockey says Trump ‘was one of the most authentic political candidates I had ever seen’, even though he was ‘confronting, rude and naive’. When he later spent time with the president, even on the golf course, The Donald was constantly questioning, churning through ideas and trying out lines:

Most political leaders are narcissists. They not only need to be the centre of attention, they often think they are the smartest people in the room. They also have fantastic egos. They believe they can charm the leg off a billiard table with their quick wit and nice smile. Enter Donald Trump.

Hockey describes a White House that lacked leadership and leaked like a sieve, with everyone competing for Trump’s attention and approval. The leaking meant the Washington Post quickly got the transcript of the president’s notorious phone conversation with Turnbull on 28 January 2017, a week after the inauguration.

Turnbull needed Trump to commit to the deal struck with Obama for the US to accept refugees Australia had exiled to Nauru and Manus Island. Trump berated Turnbull over a ‘dumb deal’ and the ‘worst deal ever’.

When Hockey answered the phone and spoke with Turnbull ‘straight after the conversation, he was shaken. His voice was quivering and he was clearly upset.’

Hockey says the Trump–Turnbull call was ‘disastrous’. The ambassador put on his politician’s helmet and marched into the White House to argue the dangers of a ‘massive deterioration in the alliance’. The public crisis—‘the madness that followed the leaked phone call’—offered a chance to lock in the deal. The strong foundations of the alliance, Hockey says, ‘can’t be undermined by the whims of a leader’.

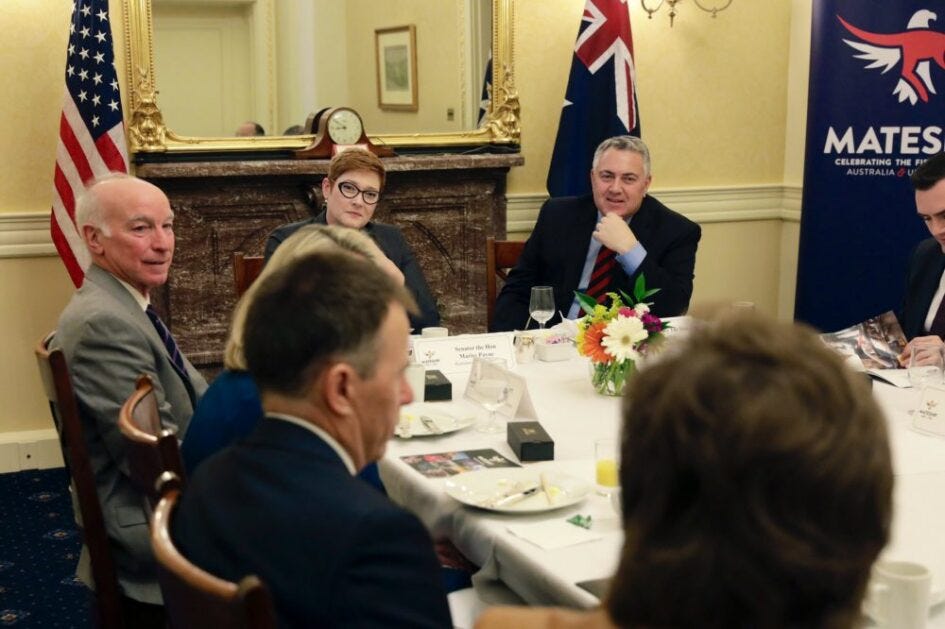

Thinking like a politician, Hockey launched a campaign with a strong story: ‘100 years of Mateship’, marking the two countries’ shared military history. ‘Australia is the only country in the world to fight side by side with the United States in every major conflict’ since the Battle of Hamel on the Western Front in 1918.

Mateship is a complicated concept for Australia, and the campaign got plenty of criticism in Oz for being blokey or subservient. For America, though, mateship struck a chord and Hockey says it became a ‘successful touchstone’. Certainly, mateship seemed to work with The Donald. ‘After the disastrous first phone call,’ Hockey writes, ‘Australia went on to have a series of political and economic wins during the Trump presidency.’

Hockey exalts that the mates theme was embraced by President Joe Biden in his address marking the 70th anniversary of the ANZUS alliance: ‘Through the years, Australians and Americans have built an unsurpassed partnership and an easy mateship grounded on shared values and shared vision.’

The Hockey prediction is that Biden will not run for a second term as president. And he links that with a prediction that Trump, too, is unlikely to run: ‘Apart from his age [Trump will be 78 in 2024], and the likelihood the Democrats will seek to legally bar him from running, I don’t think he could bear the prospect of losing again.’

With questions in the air about both Trump and Biden, Hockey judges, ‘America hasn’t been in such a precarious position for a long time.’

Graeme Dobell is a distinguished Australian journalist of longstanding and currently a Journalistic Fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

His five part series on Defence and its traditional attitude of treating journalists as Public Enemy Number One, titled Defence Confronts the Media Age, is a must read for anyone struggling to understand the Australian government’s often bizarrely counterproductive approach to journalists.

It begins here.