Bob Hawke and the Demon Drink

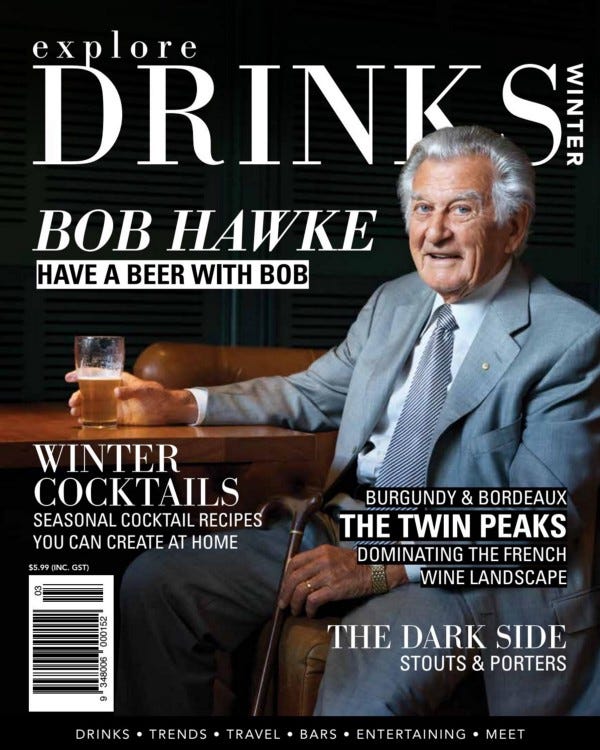

At 89, former Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke has declared himself in miserable health and unlikely to last much longer.

While he expects the Labor Party, which he led for many years, to win the next election, due by May of 2019, he does not expect to be around to see it.

Australia has survived one of the worst periods of ramshackle government in its history; with both sides of politics, excessive taxes, a bloated bureaucracy, an unaccountable judiciary and a gutless media all complicit in the fiasco.

Faith in democracy, as one recent headline declared, has hit catastrophic lows.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Bob Hawke was the last Prime Minister Australian workers felt was one of their own.

Here, before the flood of plaudits begin, is a tale adapted for Medium from the upcoming memoir Hunting the Famous.

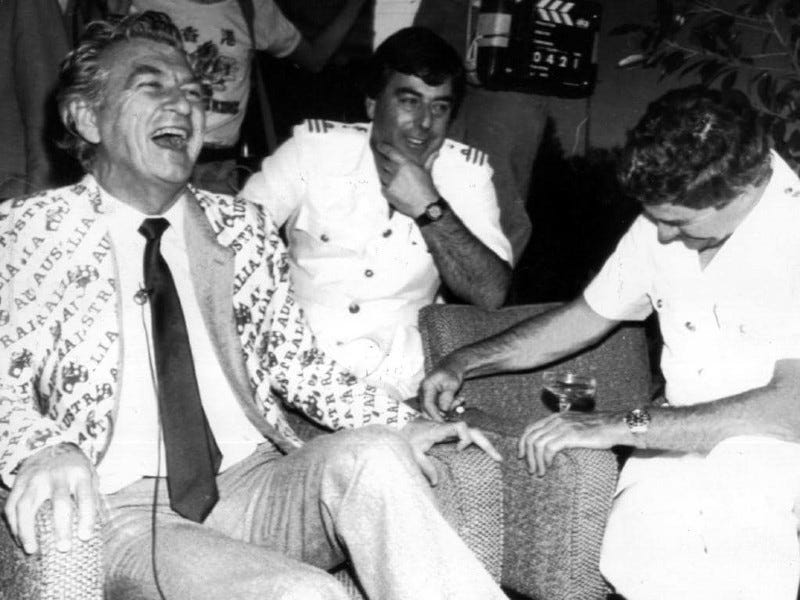

Everyone loved Bob

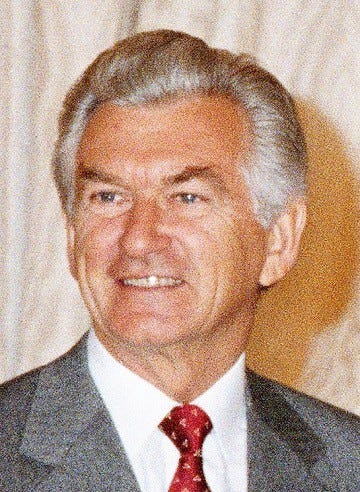

Bob Hawke, Australian Prime Minister from 1983 to 1991, enjoyed for a sustained period of time enviable approval ratings — during the 1980s the highest ever for an Australian Prime Minister. He led the Australian Labor Party to four successive election victories and to this day remains the left’s longest serving leader.

“Hawkie”, as he was often known, was the Sydney’s taxi drivers’ politician of choice.

He wasn’t just another working class hero.

Many Australians genuinely felt that Hawke was one of their own, an ordinary person with their interests at heart.

And such a person, after a string of upper-class residents, was finally going to be living in the Prime Minister’s official residence, The Lodge.

There were celebrations across Sydney when Hawkie trumped the opposition with a lightning dash, becoming Prime Minister less than four weeks after overthrowing former Opposition leader Bill Hayden in an internal coup.

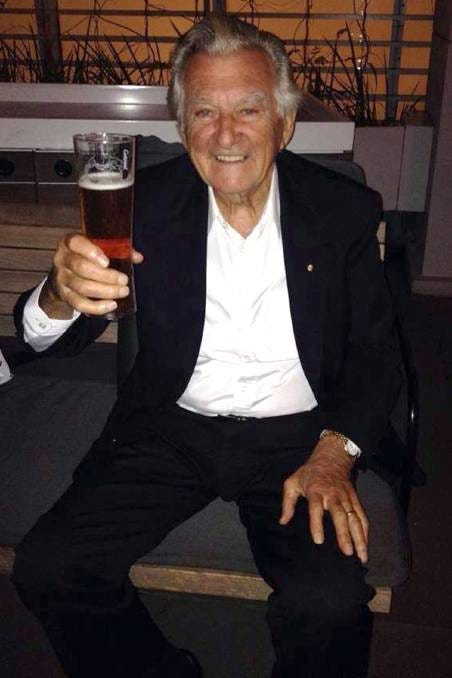

The conservative leader’s attempt to exploit disarray in the Labor Party by calling a snap election backfired and the charismatic former union leader led his party to victory.Bob Hawke in a beer sculling competition, at the age of 83.

The night of his victory I was sent out by The Sydney Morning Herald to gauge the public’s reaction.

Like many a journalist I somehow thought of the city’s taxi drivers as the voice of the common man.

I wasn’t the first and certainly would not be the last reporter, lazy or pressed for time, to grab a quote from the taxi driver on the way back from a job.

And then include the quote in the story so it sounded like the paper had surveyed half the country to discover the common sense voice of the working man. Just as I did on the night of Hawke’s resounding victory.

Clever and Accepted All At Once

Bob was clever in a nation which confused cleverness with pretension and regarded such a trait with deep and abiding suspicion.

Often enough you would never have known Bob had any more brain cells than your Average Joe.

Hawkie wasn’t about to let on to the voters he had ever read a book or could see straight through them in a micro-flash.

The ability to act like a normal working class male was a keystone to acceptance. And to his electoral success.

Hawke adopted the camouflage of the good bloke, an Australian male. It was part act, part truth.

Prior to his elevation to the Prime-Ministership Bob Hawke smoked, drank to excess, loved a party, a brawl, a fine curvy woman, he swore like a trooper and bulldozed his way through any given situation. Like many Australian men.

The dust stained workers perched on the bar stools after work took to commenting on how smart Hawkie was; how he had some English scholarship or something; but even so he was a “decent bloke”, the highest compliment one Australian male can pay another.

One of the world’s most urbanized countries, Australia was essentially a land of suburbs. Hawke was famous for going to the shopping malls of the country’s outer areas and shaking hands with anyone and everyone he met. We the media were often obliged to follow.

In that Arcadian world, prior to the Twin Towers turning security worldwide on its head, Hawke wasn’t the type of Prime Minister to hide behind a screen of police or national security officers.

Unlike the carefully scripted encounters with the “public” of his successors, Bob Hawke was prepared to take on not just the flattering praise of party members, but to genuinely front all comers. If someone wanted to verbally attack him over a real or perceived injustice, as sometimes happened, Bob would stand his ground, listen to what they had to say and promise to look into it.

Hawk’s supremely arrogant successor Paul Keating dismissed Bob Hawke’s “shopping mall” antics as cheap populism.

Forgetting that we were the conduit to the voting public, Keating also made the mistake of ridiculing the media as a bunch of low life grubs. Partly as a consequence, Keating experienced some of the lowest popularity ratings of any Australian Prime Minister in history.

When Bob Hawke committed troops to the first Gulf War, a controversial move in a country which had seen too many of its young men die in distant wars for the benefit of other nations, he slickly purloined what was an electoral risk into an issue of national pride.

To question the country’s commitment to Iraq was to denigrate, as the spin went, some of the world’s finest soldiers.

Having neatly survived the country’s natural anti-war sentiment post-Vietnam — and as common Australian decency would dictate — Bob Hawke went down to the docks on the day the first troops were being sent off to war, ignoring the band of protestors outside the naval yards.

Hawke lingered on the ship for hours, shaking the hands of every soldier he laid eyes on and wishing them all good luck.

After the official proceedings were over, Hawke wandered the battle ship decks, cheerfully posing with the soldier’s proud families.

I followed the Prime Minister, his circling minders and his ever despairing security team around the battle ship.

Follow in Hawke’s wake as a reporter, virtually all one ever found were fans. And so it proved on the day the country sent the first contingent of soldiers off to Iraq.

“Hawkie shook my hand, he touched me here, he kissed me on the cheek, I’m not going to shower for a week,” one of the mothers clutching children gushed.

“He asked after my grandmother, he remembered her from the teachers union, and said he was sorry to hear she had passed away,” another threw in.

“He wanted to know the names of my children. He posed for a picture with them. When I told him one of the kids was sick, he said he knew an asthma expert, and would get one of his staff to send me the details.”

All of this and more from the devoted constituents left in his wake. Hawke didn’t win four elections in a row without a gift for electioneering. Nobody had the common touch like Bob.

Australians loved him. That he was clever was forgiven or forgotten.

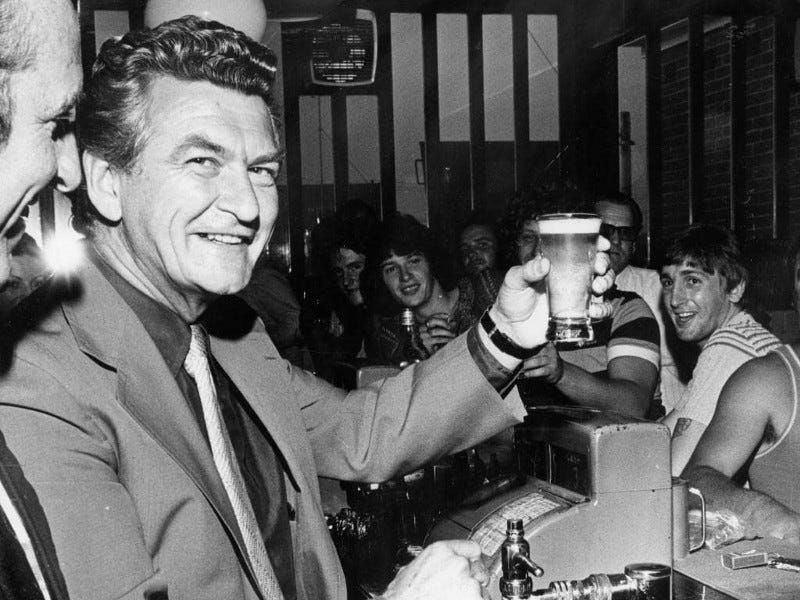

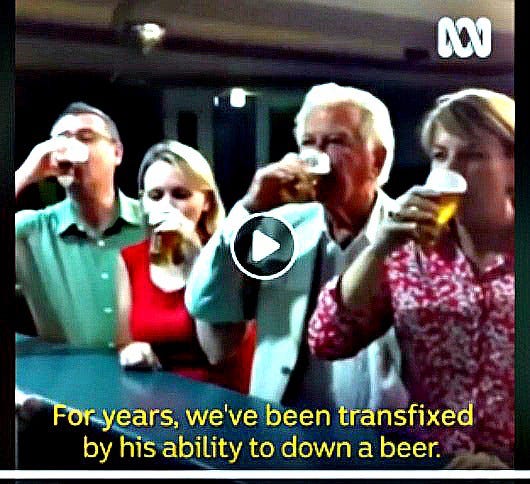

The World’s Number One Drinker

Hawkie won a Rhodes’ Scholarship to University College, Oxford, in 1956. Apart from a thesis on wage-fixing in Australia, he most distinguished himself by setting a new world speed record for beer drinking, a feat which gained him an entry in The Guinness Book of Records.

He recalls the incident as follows in The Hawke Memoirs (1994):

I inadvertently achieved notoriety as a result of one of the quaint and ancient customs of my college. A system operated at dinner in the Great Hall under which if an offence was committed — in my case coming to dinner without a gown (some bastard had borrowed mine) — one was ‘sconced’.

This meant having to drink two and a half pints of ale out of an antique pewter pot in less than twenty-five seconds. Failure to do so involved paying for the first drink, plus another two and a half pints.

My chance of avoiding payment lay in downing the ale within the limit and hoping that the Sconcemaster — the President of the Junior Common Room — could not beat my time. I was too broke for the fine and necessity became the mother of ingestion.

I downed the contents of the pot in eleven seconds, left the Sconcemaster floundering, and entered the Guinness Book of Records with the fastest time ever recorded.

This feat was to endear me to some of my fellow Australians more than anything else I ever achieved.

In a country which then had a strong beer culture, Hawke believed the feat was a significant factor in helping him become Prime Minister.

The Australia of the day lived by the motto:

“Never Trust a Man Who Doesn’t Drink.”

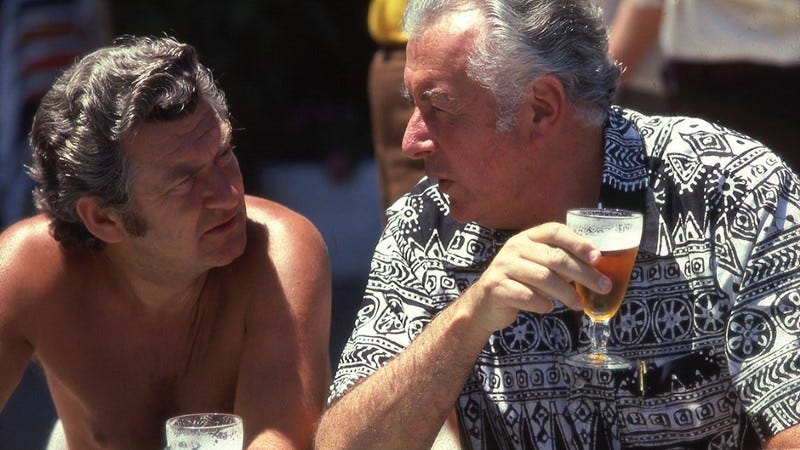

Australia’s pub and beer garden culture, once a vital part of the country’s egalitarian ethos, provided valuable community gathering points for all and sundry.

Whether you were the Prime Minister or a builder’s labourer, at the end of the day you all ended up in one place: the pub.

The culture has since been destroyed by shrinking household budgets, excessive taxes, insane over-regulation and over-policing, a bureaucratic class with contempt for working class cultures, particularly male cultures, and a weird kind of middle class New Age puritanism.

But back in the day, such dreariness was yet to had settle across the cultural landscape.

Australians loved their Hawkie even more when he told the nation in the lead-up to the 1983 election that if he became Prime Minister he would shy away from the sauce.

In what other country would a promise of abstinence made by someone running for the highest office in the land be regarded with such admiration?

It was a promise Hawke would keep, much to everybody’s amazement.

There was speculation that Hawke attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings held exclusively for high ranking government officials.

True or not; his anonymity was respected. His confessions, if he ever made any, did not become the subject of the common gossip which often infests self-help groups.

Explosion

Years after he ceased being Prime Minister, a photographer and I were sent to cover a function in Eastern Sydney for the launch of something or other, a book, a restaurant chain, a new line of doilies, an inoffensive new charity for the ladies who lunch. In the end all the launches merged into one another.

It was one of those leisurely, well catered for events where someone had thrown $50,000 or so on the table for expenses and considered it money well spent.

Everyone was well dressed. Except of course for the journalists and the photographers; the city’s riff-raff.

Hawke, like many politicians, knew half of Sydney’s media pack by name, he made a point of it, and even then, years after he lost the leadership, he knew exactly how to play them.

After the launch of whatever it was, lunch was served.

The media were placed at a table well away from the main guests so they wouldn’t spill anything on the neatly starched table cloths or overhear a confidence no one wanted to read in the next day’s papers.

Bob as always was prominently situated near the podium.

As far as pulling a living legend was concerned, having Bob Hawke at your function was about as good a get as a society hostess could pull off.

And as always, Hawkie knew everybody.

The working man’s hero was perfectly at home in the upper echelons of Australian society. This was the refined, clever, upper-crust Hawke the general public never saw.

This was the man the nation’s taxi drivers, builders laborers, electricians and hard-working masses hadn’t vote for; because they thought they were voting for one of their own.

With all the charm and discretion for which the media were renowned, The Sydney Morning Herald photographer pulled off a string of shots of Bob drinking what looked suspiciously like alcohol.

The End of the Big Dry

He was no longer Prime Minister, having been replaced by the knife edged Italian suits draping Paul Keating’s elegant form, but to everyone’s knowledge he had maintained his pledge of abstinence.

Hawkie holding a glass of what looked like white wine was the first public sign that The Big Dry was over. It had been a long time between drinks.

All of those lay-it-on-thick sympathy articles about his long suffering wife Hazel, who was admired more than any other Australian Prime Minister’s wife before or since, disappeared in the wave of a glass.

The country’s women sympathized with Hazel for all those long nights spent alone caring for the children, waiting for her husband to come home from the office or whatever function Bob happened to be attending — including all those boozy late night Australian Labor Party dinners in Sydney’s Chinatown where drinking to excess was compulsory.

And Hazel was much admired for her dignified look-the-other-way response when Hawke’s womanizing became the subject of gossip.

The parable of Hazel’s quiet heroism and Bob’s remarkable self-control disappeared with the first photograph of Bob holding a glass of “piss”, as Australians so elegantly called wine.

The Sydney Morning Herald where I then worked loved the story.

A common place launch of nothing in particular I was hopeful I wouldn’t have to file a single word on suddenly turned into a front page story — thanks to an enterprising photographer.

Wrung out from so many hundreds of stories, I wished the bloody photographer had kept his lens cap on.

In a dreary afternoon under the News Room’s fluorescent lights I was obliged to ring everyone even remotely connected to the luncheon, from experts on alcoholism to the event’s caterers.

Hawke’s press person declared that he had no idea where Bob was and as Hawke was no longer Prime Minister but a private citizen his whereabouts wasn’t a reporter’s concern.

The helpful little press person turned off his phone after I barraged him with calls.

Former Australian Prime Ministers receive ample benefits costing the taxpayer hundreds of thousands of dollars annually, but they see no need to answer a journalist’s questions in return.

The pictures of Bob drinking white wine, spread across the top of the front page proofs, looked fantastic.

The problem, the editors declared, was it could possibly be non-alcoholic white wine. It seemed unlikely. It was certainly news to me that there was any such thing.

I rang the caterers. They weren’t prepared to discuss. No, they couldn’t possibly put me on to the waiter who had been serving Hawke — they were casuals and had dispersed.

No, the head waiter could not comment and no, they couldn’t possibly pass on any of the staff’s numbers, a question of confidentiality.

The emphasis on individual privacy as a right and its progressive enshrining in legislation had already become the bane of working journalist’s lives.

The restaurant delivered up the same story as the caterers: “Sorry, everybody’s gone home now. No, I don’t have anyone’s number. No, I’m so sorry, I would like to help but I just can’t. Best of luck with it.”

Non-alcoholic white wine!?

Would someone like Hawke even drink such a thing? Was it available in Australia? And if it was, what a nightmare assignment for some marketer that must have been!

Prior to the advent of Google, there weren’t any lightning fast computer searches which could reveal every minor reference to such an oddity as the sales of non-alcoholic white wine in Australia in 0.24 seconds. Or less.

The principal wine merchants were all bemused. Some suggested they had heard of such a thing but had no idea where to buy it.

As day turned to night there was only one thought on my mind — “I want to go home”. Lunch was an increasingly long time ago.

Journalism might seem like an interesting line of work, but being constantly under surveillance from malevolent layers of Chiefs of Staff, Editors in Chief, News Editors and Night Editors, to name a few, increased stress levels magnificently.

Journalism was a high burnout high turnover profession and only naturals, misfits or hardheads survived past the first two or three years. The rest of the annual throngs of eager young cadets soon left for bigger offices, more respect and considerably better salaries in corporate public relations.

As night fell outside the Fairfax building — which to the amusement of the journalists working there somehow never made it onto The Sydney Morning Herald’s annual list of Sydney’s Ten Ugliest buildings — the brewery on the other side of eight lanes of traffic lit up for the night shift.

The editors continued to wring their hands over the possibility of being sued if the paper went with the Bob Drinks Again story.

Hawkie might have been all bonhomie to the nation’s working journalists, a seasoned master at manipulating the media who played such a crucial role in the stratospheric popularity he enjoyed for so many years.

But in fact Bob was no lover of the Fourth Estate.

After his retirement Hawkie was reported to have lined his pockets suing the news’ organisations which had dared to malign, slight or allegedly defame him during his time in power.

On the day of Hawke’s luncheon I had already reached the allotted hour for being swamped by a daily feeling of burnout. Other interests lay outside the newspaper’s precincts.

I might have been working since morning, but my bosses weren’t about to hand this story over to the night reporter.

“Ring him and ask him,” I was ordered.

“I don’t know where he is,” I replied.

“Do your job,” came the frustrated response. “Ring everybody you can think of who knows him and don’t stop till you’ve got him. Because you’re not going home until you do.”

Finally I tracked the quarry down to the bar in the Duke of Stamford hotel in Double Bay. It was the hotel of choice for the affluent and influential, discrete, tasteful and with top-of-the-line service.

“He’s not in his room, he’s in the bar,” I told the Chief of Staff, hoping I could wriggle out of making the phone call, knowing perfectly well Bob wasn’t going to take kindly to this sort of invasion.

“Ring the hotel and ask to be put through to Bob in the bar,” the Chief of Staff ordered. “It’s that sort of hotel and they’ll know exactly who you mean.”

“Ugh” I responded, grumbling as I went back to my desk.

I rang the Duke of Stamford hotel and explained to the man on the switch what I needed.

We had bonded over the previous hour of multiple calls when I dropped the hint I might “bat for the other side”.

The switch-bitch was all aflutter at the gossip that one of the reporters on the city’s Bible of the Chattering Classes aka The Sydney Morning Herald might be sympathetic. Who knew what stream of stories might change the way conservative Australia thought about sexuality; if only he was kind enough to help out a reporter with a little show of brotherhood.

After some prevarication the telephonist did exactly as I asked.

I could hear the muffled flurry in the expensive padding of that exclusive watering hole as the barman said quietly: “Phone call for you Bob.”

And I could almost hear Hawkie’s self-important “harrumph harrumphs” as he excused himself from the group he had been entertaining and went to take the call.

Once I had that instantly recognizable and most famous of Australian voices on the line and apologized for interrupting him I explained to Bob that the editors were a pack of idiots with no respect for other people’s privacy, but they wanted to run a picture of him, probably in the gossip section at the back of the paper, perhaps not at all.

But they just wanted to know if what he was drinking in the photographs at that day’s function was actually white wine.

“For Goodness sake,” Bob snapped, slamming the phone down.

The story, including the former Prime Minister’s response, along with a string of photographs, was strapped across the top of the front page of The Sydney Morning Herald the next morning.

It would be some time before Bob let his guard down enough to be photographed drinking in public again.

Adapted for A Sense of Place Magazine from the upcoming memoir Hunting the Famous.

John Stapleton worked as a news reporter on The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian for more than 20 years. A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.