Australia's Therapeutic Goods Administration Approves Certain Psychedelic Treatments

Paul Liknaitzky, Monash University.

A few days ago, the Australian drug regulator – the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) – surprised experts around the world when it announced the approval of certain psychedelic treatments.

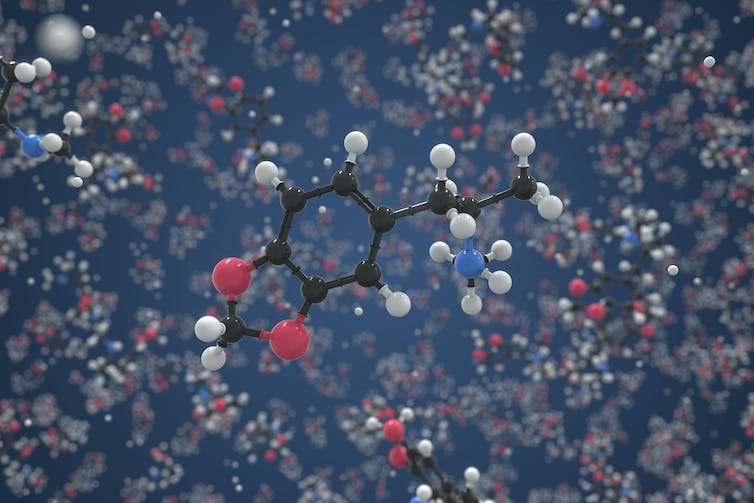

From July this year, the TGA will permit authorised psychiatrists to prescribe psilocybin (found in “magic mushrooms”) for treatment-resistant depression, and MDMA (found in “ecstasy”) for post-traumatic stress disorder.

I head up Australia’s first clinical psychedelic lab, where we develop psychedelic-assisted therapies for treating various mental illnesses, test their safety and effectiveness, explore how the treatments work, and train therapists.

I’ve witnessed, up close, the rapidly accelerating developments within the field and in positive public sentiment, over a few short years. But this surprising announcement may have devils – and angels – in the detail.

In from the wilderness

Just a few years ago, Australia had no psychedelic research, almost no professional interest, and negligible public awareness of the clinical potential of these treatments.

The first psychedelic trial in Australia was approved in 2019. We established the country’s first clinical psychedelic lab in 2020. And by the end of 2023 there will be more than 15 active clinical psychedelic trials nationwide.

While the TGA’s announcement was hailed as groundbreaking, there are actually a handful of places where psychedelic-assisted therapies have been approved for very limited clinical use outside of research trials (for example, compassionate or expanded access programs in the United States, Canada, and Israel, and a version of authorised prescribers in Switzerland).

But this is the first time a government has changed the way these drugs are formally classified (“scheduled”). This may turn out to be a distinction without difference, as only so-called “authorised prescribers” will be approved to use these drugs outside of trials; or instead, it may turn out to be be a watershed moment with dramatic effects on the field globally.

Emerging evidence

Emerging evidence shows that, when used alongside psychotherapy, certain psychedelic drugs can be safe to administer and produce large, rapid and sustained benefits for a range of addiction and mental health conditions. These include post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, end-of-life distress, alcohol use disorder, and nicotine dependence.

While there are some important research limitations associated with these studies, the results have been compelling.

Cautious optimism

Since the announcement, I’ve spoken with numerous clinicians and researchers working in psychedelic trials in Australia, and all have expressed mixed reactions to the TGA news.

There’s excitement: about drug policy progress; about potential access for more people in need; about the prospect of being able to offer patients more suitable and tailored treatment without the constraints imposed by clinical trials and rigid protocols.

And then there are concerns: that evidence remains inadequate, and moving to clinical service is premature; that incompetent or poorly equipped clinicians could flood the space; that treatment will be unaffordable for most; that formal oversight of training, treatment, and patient outcomes will be minimal or ill-informed.

Many professionals working at the coalface are concerned that soon-to-be prescribers, therapists, and decision-makers probably don’t know that they don’t know about some of the essential elements of safe and effective psychedelic therapy.

https://twitter.com/SBSNews/status/1621434935419576324?

Read more: Latest trials confirm the benefits of MDMA – the drug in ecstasy – for treating PTSD

Angels or devils

The TGA announcement cites promising evidence as the basis for its decision. However, its approach does not appear to account for factors that may be key to this evidence base, and leaves some critical questions unanswered. Here are a few things to watch:

Who treats?

The TGA decision permits only authorised psychiatrists to administer this treatment, and states “the product must not be supplied to other practitioners who prescribe or administer the product”.

While psychiatrists are an important part of a collaborative care model, they will need substantial psychedelic training to deliver this complex form of drug-augmented psychotherapy. What will constitute adequate psychedelic training is unlikely to be clarified, nor is there a requirement for practitioners to be supervised by psychedelic experts.

Psychedelic therapies are so dissimilar to general psychiatry that simply trusting that psychiatrists “have the training and expertise […] to appropriately treat” patients using psychedelics is ill-informed.

Moreover, any requirement to have psychiatrists attend all treatment sessions (dosing days typically last eight hours and a typical treatment model involves about 40 hours of therapy) will make this even less affordable.

Any prospective authorised prescriber will need extensive training and ongoing supervision from credible professionals who have experience delivering psychedelic therapy, and should establish collaborative care teams with qualified psychologists and psychotherapists.

Who is treated?

The evidence for safe and effective psychedelic treatments comes from trials with very strict eligibility criteria. Over 90% of applicants to these trials are typically excluded.

Trials are cautious, in part because we know these treatments can destabilise people, exacerbate certain symptoms, and increase suicidality. The excellent track record of safety across almost all modern psychedelic trials has been established in the context of extensive screening.

Authorised prescribing will open up the eligibility to a greater diversity of help-seekers. This is a good step, but should be well-informed, and taken with caution and transparency.

What does treatment involve?

Since 1999, clinical psychedelic trials have delivered psychotherapeutic support before, during, and after the drug administration, with one to three dosing sessions. The TGA decision does not mandate any of this, advising “there does not currently appear to be any established treatment protocols”.

This is a misunderstanding. While treatment protocols across trials are not all the same, they certainly exist, and there is considerable overlap in the therapeutic approaches used. Improved protocols will be developed over time, but a sensible approach is to start with an approximation of what has been done in trials that have shown safe and effective outcomes.

Are patients informed before they consent?

Practitioners need to make informed decisions about any departure from precedent, and be transparent about those details with patients.

For example, if a prescriber does not provide therapy, does not have psychedelic training or supervision, or offers more than three dosing sessions, patients need to know which aspects of their treatment sit outside the evidence base.

Wider prescribing will effectively entail a “community-based experiment”, and a basic right of all patients is that they are able to make informed decisions about their treatment.

A brave new world?

There are many other questions worth grappling with over the next five months, including those regarding appropriate oversight and patient protection, affordability and reimbursement, and public expectations and awareness.

I feel cautiously optimistic that many more Australian patients may be able to access safe and effective psychedelic treatments, and that the Australian mental health care sector has an opportunity to learn how best to deliver them.

To those planning to work in this space in Australia, I urge you to start or continue climbing the steep learning curve with curiosity, to organise reputable training, support, and resources from those already doing the work, and to establish appropriate systems of governance, oversight, and transparency.

There’s so much potential here, plenty at stake, and work to be done.