An Interview with Gigi Foster, Warrior Against Lockdowns. The Best of 2021.

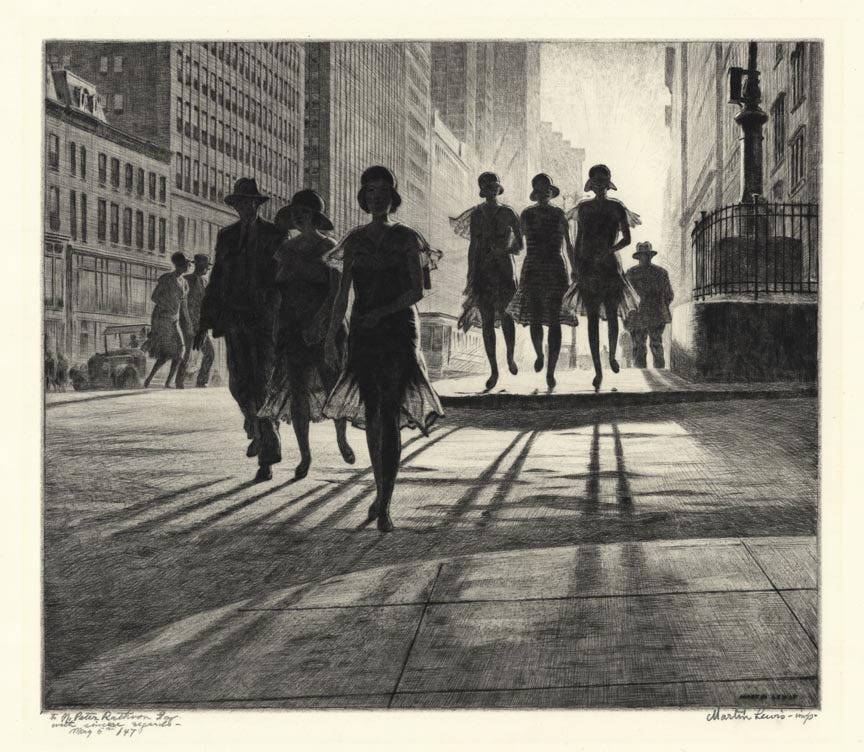

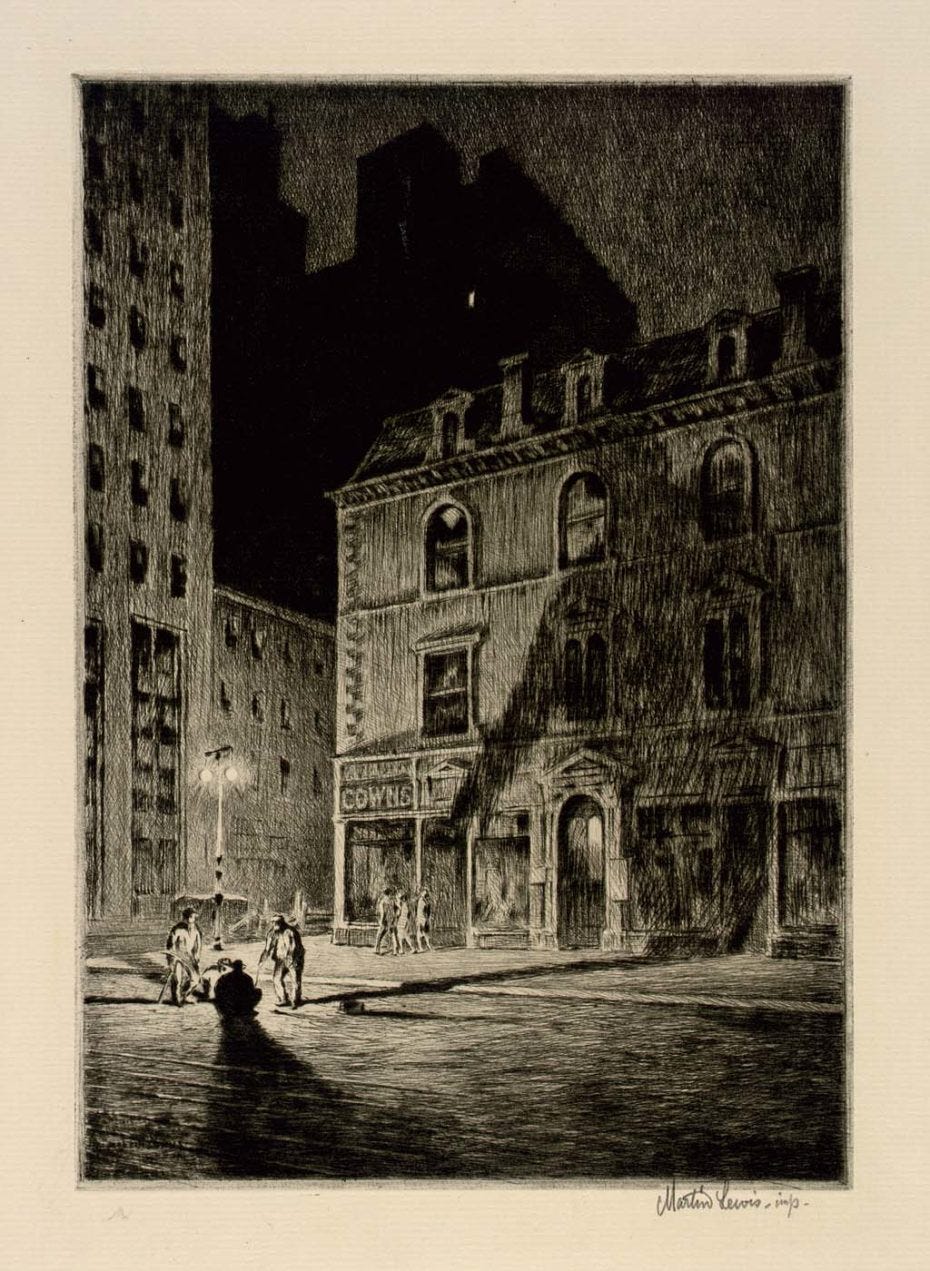

From the Brownstone Institute. Featured Artwork Martin Lewis.

Gigi Foster, economic professor at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, is co-author of The Great Covid Panic (Brownstone Institute, 2021) and a fierce opponent of lockdowns and mandates that have caused so much damage to Australia’s economy and long-standing tradition of human rights. Jeffrey Tucker of Brownstone interview her in this detailed interview, as her book is growing in influence in Australia and around the world.

She explains her views and reveals how much of her life has been changed by being such a public proponent of opening up society. “I don’t know if I’m going to be embraced back into the community of economists in Australia ever, in the same way,” she says.

“I’ve got people who absolutely hate my guts. Won’t go on to debate with me. I’ve had multiple appearances where the host tries to find someone who will be there with me and kind of provide a counterpoint and nobody will do it. They ask multiple people, they won’t do it. People hate me. People see me as literally the devil.”

Jeffrey Tucker:

Tell me, which sections you like the most?

Gigi Foster:

I tell you that the Crowds chapter seems to be the most impactful for many people, because they just haven’t thought about the crowd dynamic, previously, because we haven’t observed it really, in our lifetimes, most of us. Or we sort of learned about crowds, but I never really thought it could apply to our lives today, so I think that is really a useful one. And also, people like to hear about the scale of the tragedy, just from a very objective standpoint. What have lockdowns done to us. What have we lost.

Sometimes, the political economy just generally unto the Middle Ages analogy, the analogy to feudalism in today’s sort of way in which corporations and governments collude and control populations more than we might think.

And also the bad macro section, that’s one that’s popular. And I like that one because it’s basically taking a direct aim at some of the people within the academy, my colleagues, unfortunately, who have just gone right along with his madness and been apologists for it. And it illustrates the corruption of science during this period, from a very personal standpoint, because obviously, all three of us are economists. And we’ve seen some of the worst rationalisations. I mean, worst in the sense of most offensive and non-aligned with the goals of economics in normal times, coming out of our discipline.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Right, it’s a bit of a shock, which is I think one of the reasons that when I first read the manuscript, I think it was that section on Crowds that affected me, too, the most. I was surprised at just how weirdly calm that section is. Because like lockdowns are a massive violation of every principle of liberalism, as we think about it, as and so that section is like dial backing, right? You were very patiently explaining.

https://asenseofplacemagazine.com/the-great-covid-panic-a-book-review-a-meditation-on-this-imperilled-time/

Gigi Foster:

We thought that was necessary because we were just surrounded by people who have bought into the lockdown ideology. And they will have in their minds, a very facile sort of reason why lockdowns should work. And so, we addressed that very directly in that section as you know. We say, “Look, on the surface of it, the idea is that you prevent people from interacting with each other and therefore, transmitting the virus. That’s what people believe. That’s what they think when they think lockdown, they think, “That’s what I’m doing.”

But they don’t realise how many other collateral problems are happening and also how little that particular objective is actually being serviced, because of the fact that we live in these interdependent societies now. And we also are trapping people often in large buildings, sharing air together, and not able to go outside as much and so we’re actually potentially increasing the spread of the virus, at least within communities, our communities. So, it basically is an example of trying to engage with the people we feel are misguided on this issue in a calm way, not screaming at each other, not sort of taking the radical position on either side and just saying, “I’m going to play gotcha with you” because that’s not productive.

That is also one of the principles of classic liberalism. You have to be able to investigate and try new things, experiment and engage with each other respectfully and be open. And not get stuck in the mud and into routines and with just some narrow monovision that you disobey, you get ostracized from the group. That’s just not the way to develop a healthy society.

Some chapters were hard to write in that calm way because all three of us are absolutely, just deeply offended and incredibly angry. And we’ve got in the depths of despair like I’m sure you have as well as seeing the destruction during this period. And it’s just, it’s heart rending, heart rending. I do put a bit of it into the chapter on the tragedy where we talk about the cost of these lockdowns. But in terms of the scientific presentation, we try to keep the emotion out of it.

Jeffrey Tucker:

I liked your chapter on viruses and immunology and immune systems, too because one of the things your whole section on lockdown builds up. You’re like, “Well, this is not practical. Maybe you can avoid the pathogen if you lock down. Maybe.” But that’s not how we’ve chosen to live and that’s not the reality of the world. But there’s a slight problem with that too, because then you get this naïve immune system problem, which is potentially more deadly, even more than governments.

Gigi Foster:

It is basically one of the fundamentals of Virology in terms of Virology 101, you learn about the importance of a natural immune system, and that is our main primary defence against pathogens in general. And we’ve just sort of forgotten that that exists during this period, in terms of our policy responses. And indeed, lockdowns have a number of really negative effects on people’s immune systems.

We had to separate from other people. We’re not outside. We’re not getting the sunlight. We’re not having exercise as much. We are more stressed, so we eat things that are worse for us. And all of those things we know are bad. There’s all sorts of damage that we do to our society’s immune systems when we lock people down. For us, it was very straightforward: “Here’s all this knowledge that seems to have been forgotten in the fog of war, so let’s just put it on the page. All right? Just, let’s remember who we are here, right?”

Jeffrey Tucker:

This is pretty scary from a scientific point of view. So much for the Whig view of history, the view that that world is getting smarter and better.

Gigi Foster:

It’s interesting. I have had some conversations during this period with people asking me, “How is it that everybody has become so dumb? It’s like the entire general IQ has just plummeted, right?"

There’s several things to say about that. One of them is that we have seen the Flynn effect in operation before now, anyway, right? So there is this sort of gradual potential slide in IQ, which happens when we have some of the influences on ourselves that we have today that we didn’t have, say 30 years ago.

Editor's Note: The Flynn effect refers to an increase in population intelligence quotient (IQ) observed throughout the 20th century. The changes were rapid, with measured intelligence typically increasing around three IQ points per decade. According to the Flynn effect theory, the increase in IQ scores can in part be ascribed to improvements in education and better nutrition. In addition, people are reading more, and new technology - computers, internet - forces people to think more abstractly.

Gigi Foster: Certainly, I would say social media and the influence towards reduction in length and depth of thought that our environments have. People talk about obesogenic environments. I mean, there’s got to be a term for environments that generally decrease and depress your ability to think. And so, that I think has definitely been the case. But I would also say that, in my observation, the correlation between IQ and sense making, during this period has been virtually zero.

Jeffrey Tucker:

One of the things I’ve observed is that, typically it’s the ruling class or the upper class that the most educated people who have been the most in favour of lockdowns, but that may be a class interest issue. There does seem to be some relationship between high intelligence and high stupidity on the matter of lockdowns.

Gigi Foster:

There’s a couple of things going on. Their self-interest is properly understood. To be able to make advantage for yourself out of this tragedy. And then that drives the incentive to come up with beautiful rationalisations.

People are vulnerable to the influence of the crowd no matter what their IQ is, right? Plenty of people in crowds of the past have been smart people. It’s not like this somehow attracts only the dumb.

And also they’re very coddled really in their modern lives. That’s been another problem. A lot of the elite are in this, as you call it, the laptop class. They have been the ones making the policy. They’ve been protected from any of the risks that used to be just completely de rigueur in our lives.

The people on the street who are, the truckies or the people cleaning the roads, or the repairman or whatever, they are used to taking risks kind of as a normal part of life anyway, and they’re close to the reality. They’re right there at the coalface and so, they just don’t have the luxury of being able to wring their hands over a virus that is at 99.9% recovery rates. And for which there is now early treatment.

And to actually stop society, plus, they’ve got the back pocket reason as well, which is they need the money to survive. They don’t necessarily have the big bank balances that many of the laptop classes have been able to rest on during this period.

Jeffrey Tucker:

There is a long history of the ruling class or the upper classes or the upper tier of society, to imagine themselves to be both clean and deserving of a greater degree of cleanliness than others.

Gigi Foster:

Definitely. And I mean, that’s really interesting, too, because it shows how culture is a product of economic circumstance. And in this case, circumstance related to health. I mean, it is just true that really nasty diseases can sometimes pass more easily in dirty environments and that means that yes, there is a risk there. Now, it’s not as extreme as obviously it’s being depicted, but it certainly is something that’s real. And then once you sort of hook into that as a culture and make it part of your ideology, it can be extremely divisive.

And we start to then see these sorts of very exclusionist ideologies come up that are also very conveniently in the service of keeping the elites or the top class segregated from the unclean. And of course, so then a mechanism of power retention. So, it is this really interesting combination of factors that really are about culture responding to the circumstances of the organism.

Jeffrey Tucker:

So, you have this interlocking relationship now between moral prudery and biological cleanliness. And that all comes together with the vaccines, right? So, if you get the shot that makes you clean and it makes you also a good person, it makes you smart. If you don’t get the shot then you’re dirty and you’re stupid.

Gigi Foster:

Well, that and a danger to society.

Jeffrey Tucker:

And a bad and immoral person. So all this is coming together, it’s like this big crash and it’s hard even to talk about it because people just absorb these messages and blend them all into a big mush.

Gigi Foster:

Isn’t it amazing? Isn’t it amazing? I mean, the human brain is just the most amazing thing. I mean, I find it, it’s so easy for me to get up in the morning be motivated, because I just find it unendingly fascinating how incredible our brains are. And one of the great, one of the amazing things about them is that we have this capacity for extraction, which just allows us to do so many things. Which no other animal can possibly conceive of doing. But at the same time has the potential to lead us down the garden path, as they say, in Australia. To go off the rails really badly.

Because when you and I say something, some abstract thing like say liberalism or freedom or something, you and I may think that we are in full agreement about what that thing is and what it means the implications. We have a whole little mental model about that abstraction in our heads. But I can guarantee you that the model, the actual specifics of the model in each individual person’s head, who is saying the same abstraction is different. And so at the same time, that abstraction allows us to unite as a people, we also have this ability to kind of develop different ideas about what it really means.

Jeffrey Tucker:

It just occurred to me that you’re talking about, we’re talking about whether and to what extent a person is vaccinated. One vaccine, two, three. The most clean person has like five or something like that. But isn’t it strange how we have a confession culture, too, right? So, everybody has to reveal this. And I’ve been asked this all time in interviews, “Well, have you had the vaccine?” I’m like, “I’m just not going to say.” We’re supposed to have had this sort of respect for privacy. That seems to be almost entirely gone.

Gigi Foster:

Yeah, I know totally. We have a little movement here in regional New South Wales, which is called “#notmybusiness.” And it’s actually by business owners. And the idea is that they are going against what the state has prescribed in terms of basically having a medical apartheid system where you’re not allowed to come into the business unless you have vaccination proof, evidence. And they’re putting up on their storefronts, this #notmybusiness.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Nice, nice.

Gigi Foster:

And there’s a little video that goes along with it. And says, “We don’t believe in medical apartheid,” and all those sort of thing and the thing is that like any other kind of discrimination, discrimination based on the medical status is at the end of the day an extra cost on doing business.

And we know from discrimination studies in Economics, the economics of labor markets, where we’ve looked at discrimination, we know that if there’s even just one company that isn’t discriminating that company can eat the lunch of everybody who is discriminating because they don’t have to pay all the costs of keeping all the other people the unclean out, right. And so as soon as you allow for just a little bit of that then there should be market forces that kick in to assist the rejection of these damaging discriminatory policies.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Let me ask you, it’s a very interesting question, because I know a lot of people are going to be listening who are Americans that they know now that you’re living in Sydney. I mean, you’ve been there the whole time, right? So, I think Americans might have a tendency to otherize Australia’s policies in the full intent. And maybe I’m speaking about myself, but I found Australia’s policy of Zero COVID preposterous from the very beginning.

I was like, “Well, you’re a tourist country filled with intelligent people, why would you want to deliberately create by policy naive immune system for an entire country and thereby wreck your position in the world economy. And don’t you know that you’re going to be made a laughingstock of the world if you keep this up?

Gigi Foster:

There’s also a very strong name and shame, a culture that’s come up that’s really made itself known during this period. And you’ve seen it in terms of what happened to me last year. When I spoke out, I was ridiculed and defamed on Twitter, even though I’m not even on Twitter. And I was called all manner of names, granny killer and neoliberal Trump supporter, death cult warrior, or whatever.

And anybody who’s paying attention will see that kind of behaviour. And even if they disagree with a policy, so are they going to really speak up and just ask for that kind of abuse? No, they’re just not. And there is a culture in Australia of following authority and if you put that together with really, they have a very strong desire to be accepted by your group, which is where there’s mate-ship kind of culture comes from, too. That combination means that a lot will just say it’s silenced in public.

Now, in private, yes, I mean, I’ve received thousands of emails from people and some of them the most sweet, heart warming, full of gratefulness and gratitude and love and support. And just saying, “You’re our saviour.” I have been likened to Joan of Arc. I don’t need to add anything more to my feel-good folder. It’s amazing what people have written to me, but in private, right? Because they are afraid of that kind of cancellation. I think the other thing that really, really assisted, unfortunately, in solidifying and locking in this political narrative of “we can keep COVID out” is the fact that we are an island nation, yeah.

And so, the politicians simply were presented with this possibility. It seemed very, very tempting, almost very seductive at the beginning of saying, “Well, yes, we can protect you from the thing you’re so incredibly frightened of, by locking us down, locking us away, right? We won’t let anybody else in.” So, it just plays right into that clean/unclean ideology. And once the politicians start playing that tune, it becomes extremely hard to change keys, because you backed yourself into a corner. And that’s why we ended up now having this vaccine hero story. And really no conversation at all about early treatments or randomized control trials for prophylaxis or anything.

We had ivermectin banned by the Therapeutic Goods Administration. I mean, these crazy decisions, which, even if it doesn’t work, don’t ban it. Ivermectin is one of the safest drugs around. And so you just, you look at that and you just think, it is a response to what has happened in the political sphere here, which has been assisted by our existence as an island nation, just like New Zealand, unfortunately.

Jeffrey Tucker:

But New Zealand seems like a more extreme version of Australia, like Ardern. Somebody asked her, said, “Look, I know you don’t want to think about it this way, but it seems almost and somebody could describe it that you’re trying to create a two-class society of the vaccinated and unvaccinated, the free and the unfree.” She said, “Yep, that’s exactly what we’re doing.” Did you see that interview?

Gigi Foster:

I didn’t see that interview, but it doesn’t surprise anyone that it’s absolutely offensive. It’s so offensive. I’ve had people sending me photos of just the signs on the walls and sort of shop fronts that says, “Proof of vaccination needed. All the welcome, proof of vaccination needed.” It is like 1984. This sort of, and Melbourne, of course, the clarion call was, what was it, “Staying apart keeps us together,” right. It’s Georg Orwell again, I mean.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Well, that was and the songs and everything, it was just a little bit much. And that was already the summer of last year when they’re doing all these, “Staying apart keeps us together.” Whatever the thing is. Now, what do you make of all the lockdowners investing everything in the vaccines, but now, it turns out and we learned this, that the vaccines are, as they say, leaky.

So and now, we’re talking about boosters, and then even those are not quite doing the thing and so on and so on. So, my impression is that a lot of the proponents of vaccines really thought that this was going to be their way out of lockdowns. But now, it turns out that they are not, I’m not sure how widely understood that is. But all the data I’m seeing suggests that they’re not.

Gigi Foster:

Totally agree. I think the most logical direction for things to progress is that as we learn about the vaccines’ fading protection, also potentially, nasty side effects and long-term effects we don’t even know about, I think the easier pivot will be towards something that is more efficient, and just less costly to enforce at a business point of call. And also in terms of vaccine passports or whatever. It just becomes too difficult.

But still, the cost, the incremental costs are constantly checking to see if everybody’s vaccine status, we can’t maintain that.

Jeffrey Tucker:

The other thing, Gigi, if I may say so and every time I bring this topic up, people want to shush me. But what about those who just have made the rational decision, maybe they’ve never been exposed to COVID, but they like a robust immune system and they’re willing to be a little bit under the weather for a few days? In exchange of which you get immunity, so…

Gigi Foster:

Yeah. It’s a touchy subject. I tend to agree with you, Jeffrey, I think that people should be free to put themselves into a situation in which they may risk being infected. I know that there is a kind of a moral argument against that, that is mounted frequently by, particularly people in the medical profession, who say, we would never want to be advocating for someone to voluntarily be infected with COVID.

Jeffrey Tucker:

But should people be free to live their lives normally, even without a proof of natural immunities, even without this?

Gigi Foster:

Yes.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Because based on an individual risk calculation, I’d rather take the risk of COVID.

Gigi Foster:

Completely agree with you.

Jeffrey Tucker:

That’s been my position from the beginning.

Gigi Foster:

Completely agree. Look for my personal life. If I were a queen, which I hope I never am and I hope nobody ever is, but if I were a queen then we would drop all of this stuff right now. We would open all borders. We stop all the testing. We stop all of this stuff. What we would do is protect people who are in the old care communities, aged-care homes, and we would be investing heavily in prophylaxis and early treatment. And of course, we would keep the vaccines on hand in case people wanted them.

But we would also be doing, very rigorous independent, long-term testing on side effects and other kinds of things where we’d be encouraging development of other vaccines, technology and other technology to treat this thing. Right? But we would immediately drop all, but that’s me. That’s me being queen.

In terms of the natural immunity question. I mean, to be frank, I would rather risk exposure directly to the virus than take one of the current crop of the COVID vaccines based on the data that I’ve seen.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Right. So, what is the political outlook there in Sydney? Because you don’t have a Dan Andrews there in Sydney relative to Melbourne, right?

Gigi Foster:

Honestly, no. Yeah, so Melbourne is the capital city of the State of Victoria and the Premier of the State of Victoria Dan Andrews is the person and the premier across all of the State Premiers in Australia who has gone the hardest and the most draconian in terms of these restrictions on liberties. And we have all manner of political cartoons now. Danastan. It’s hilarious.

We had here in New South Wales, a Premier named Gladys Berejiklian, who got embroiled in a corruption scandal thing. And so, she very quickly stepped down. And I think it was not just the corruption story, I think it was probably something else to do with, COVID policy. And we now have a new Premier, who has been a staunch advocate in the past for liberty. He’s very religious. He has six kids, a Catholic, I think. But he’s very much in favour of freedom.

And so, I’m cautiously hopeful about that. the way that Ron DeSantis has done in Florida. There are lots of pressures to stop this foolishness.

Jeffrey Tucker:

In Australia, you can’t travel to Victoria. You can’t travel to Western Australia. You can’t travel anywhere.

Gigi Foster:

I can’t travel to Queensland. And I mean, I’m thinking of trying to get to Victoria in another a couple of weeks. I’m supposed to be speaking there. And so, we’ll see whether things change by then. But it’s ridiculous, these domestic lockdowns, on top of the international borders being closed. If you’re going to close the international borders, that’s bad enough. But then to, on top of that, put everybody into this lockdown state, I mean, it’s madness.

I think as soon as you start looking at the idea of doing cost benefit analysis for lockdowns, you realise that they’re a madness, so they can’t be defended.

We basically shattered what you and I have taken for granted, and most everybody is taking for granted for the last, the better part of 70 years, which is the freedom to travel here and travel there and do what you want.

I think back to my childhood. My mother took me around the world. I was 11 years old on something called the Semester at Sea program where we stopped in 10 different countries, 10 different ports. And we were literally on a ship going around the world. And those experiences that I had, during that trip, were formative for me. I mean, I was 11. I was soaking up all these different cultures and different ways of thinking and, just the diversity that you see, kind of experience.

And it saddens me that we have kept now two years’ worth of our young people from having those kinds of experiences.

I really feel this is going to create a cost that is not being recognized at the moment, either even by people who are looking at the disruption to education that we’ve inflicted upon our children and thinking about the long cost of that. But this exchange and being able to visit other cultures, it’s hugely important for keeping us a peaceful and vibrant society.

Jeffrey Tucker:

Well, we’ve lost. I mean, economists for a couple of a hundred years have tried to alert people to think a little bit abstractly about the unseen costs, not just the direct costs, but the unseen costs of the things we do.

Gigi Foster:

Well, I totally agree and I mean, it’s been amazing, being an economics educator during this period, I teach economics here at the university. And one of the courses I teach is a first year one called Economic Perspectives, where we talk about the big ideas of economics. And of course, opportunity cost is a huge one.

And the story of the Parable of the Broken Window by Frédéric Bastiat, is a great one, which is the little boy comes up and throws a baseball or something or a stone through a window. And first people are like, “Oh, that’s a pity.” But then they say, “Well, at least, it will give work to the glacier. At least, we’ll be able to put him to work and that will help the economy.” And of course, Bastiat’s point is, “Yes, but wouldn’t it have been better to take that money and do something else to improve everybody’s life and livelihood and length of life and all the things we want, instead of having to fix something.”

And those spendings from the private sector and public sector individuals, they directly promote human welfare and that’s what we have sacrificed and it’s so difficult to have that conversation with people who have been wrapped up in this narrative of, “Look at what’s in front of you and respond only to that. Look at the suffering of an old person on a ventilator with COVID and respond only to that. And if you don’t respond only to that you are a bad person.”

Jeffrey Tucker:

Long term. Do you want to put a date on that? What are you thinking in your own mind in terms of like if you are going to imagine a time period in which people have shaken off this group psychology of panic and hysteria and anti-liberalism and we find our way back towards civilized principles of living?

Gigi Foster:

There are lots of factors obviously and I don’t have a crystal ball, but the kinds of pressures that we are seeing now in very kind of embryonic form, I think will get stronger and they take a while to flow through the system. So, for example, one of the big pressures in favour of recovery is that some areas of the world like Florida or Texas, or Sweden will be back to normal. And to the extent that people will be able to see that, and recognise and be jealous of that.

They will put pressure on their own home politicians or they will simply move if they can travel. So, if they are able, they’re granted permission to go to some other place, which is having a more joyful and vibrant approach to life and they will do that. And that will eventually deplete the populations in the areas which have clung on to this damaging ideology.

During this period, there’s been no scarcity of facts and evidence. The scarce thing has been common sense. And really that it is not something that you need to have a PhD to work out, which is why we’ve seen the most sense making, coming from people like the truckies or the repair people, or there’s the blue collar workers because they can sniff a rat.

Jeffrey Tucker:

That’s right. Gigi, thank you so much for visiting with me tonight and for writing this amazing book that I’m certain will stand the test of time.

Note: The transcript has been edited by A Sense of Place Magazine.

About: The motive force of Brownstone Institute is the global crisis created by policy responses to the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020. That trauma revealed a fundamental misunderstanding alive in all countries around the world today, a willingness on the part of the public and officials to forego freedom and fundamental human rights in the name of managing a public health crisis, which was not in fact managed well in most countries. The consequences were devastating and will live in infamy.

The Interviewer: Jeffrey A. Tucker is Founder and President of the Brownstone Institute and the author of many thousands of articles in the scholarly and popular press and ten books in 5 languages, most recently Liberty or Lockdown. He is also the editor of The Best of Mises. He speaks widely on topics of economics, technology, social philosophy, and culture.

The author: Gigi Foster, senior scholar of Brownstone Institute, is a Professor with the School of Economics at the University of New South Wales, having joined UNSW in 2009 after six years at the University of South Australia.

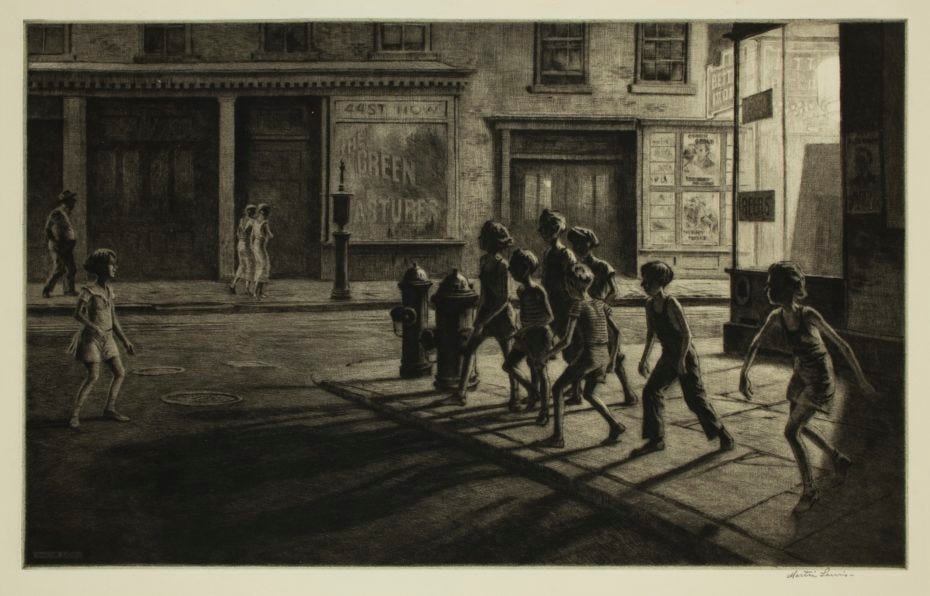

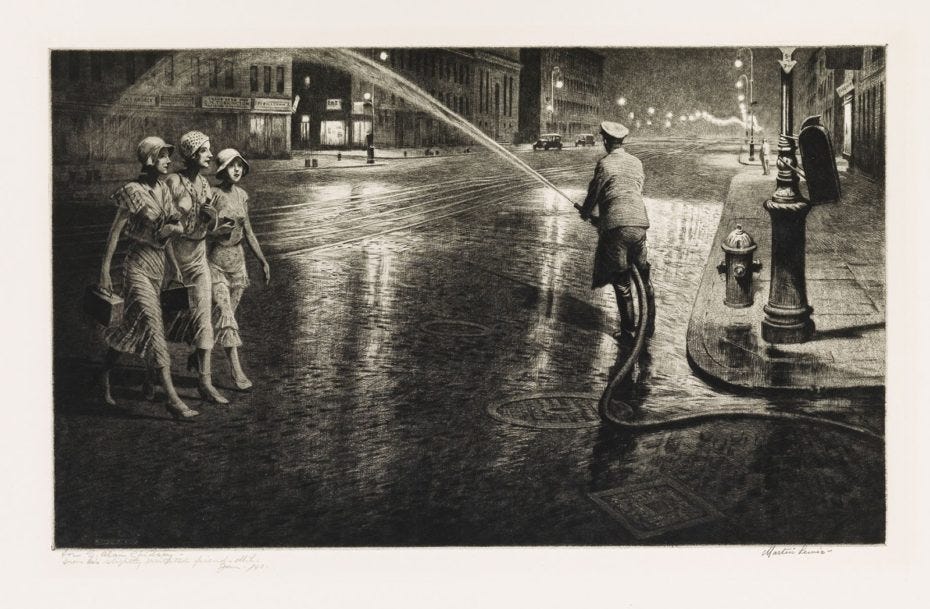

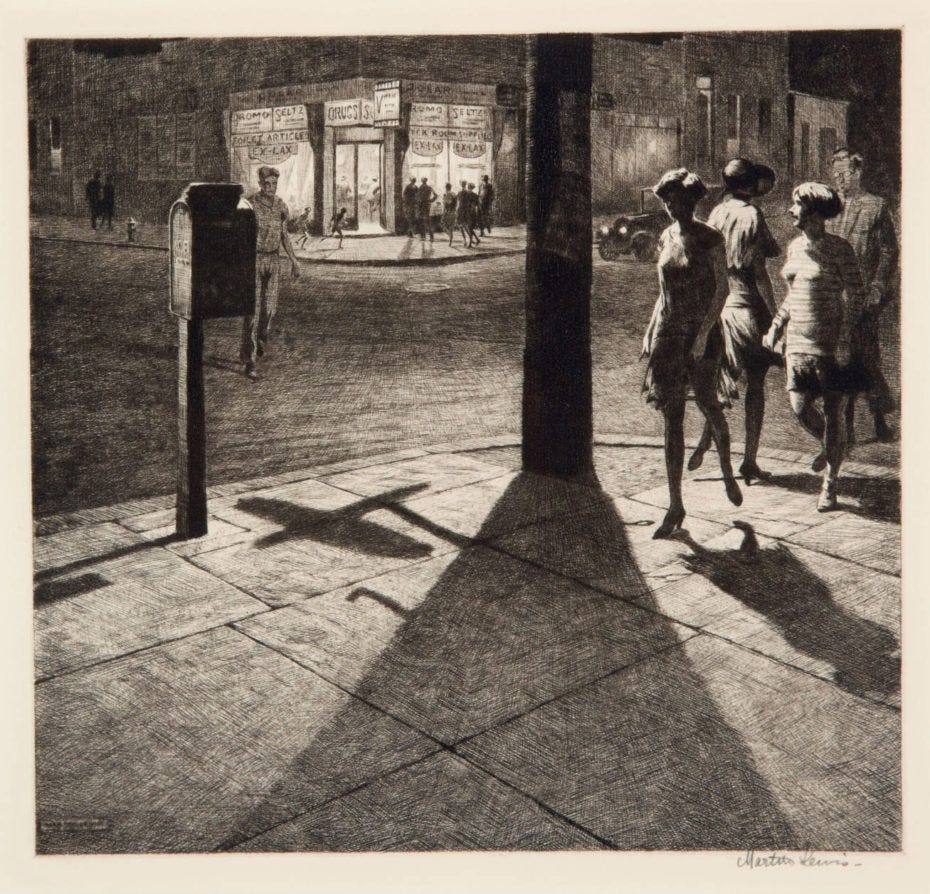

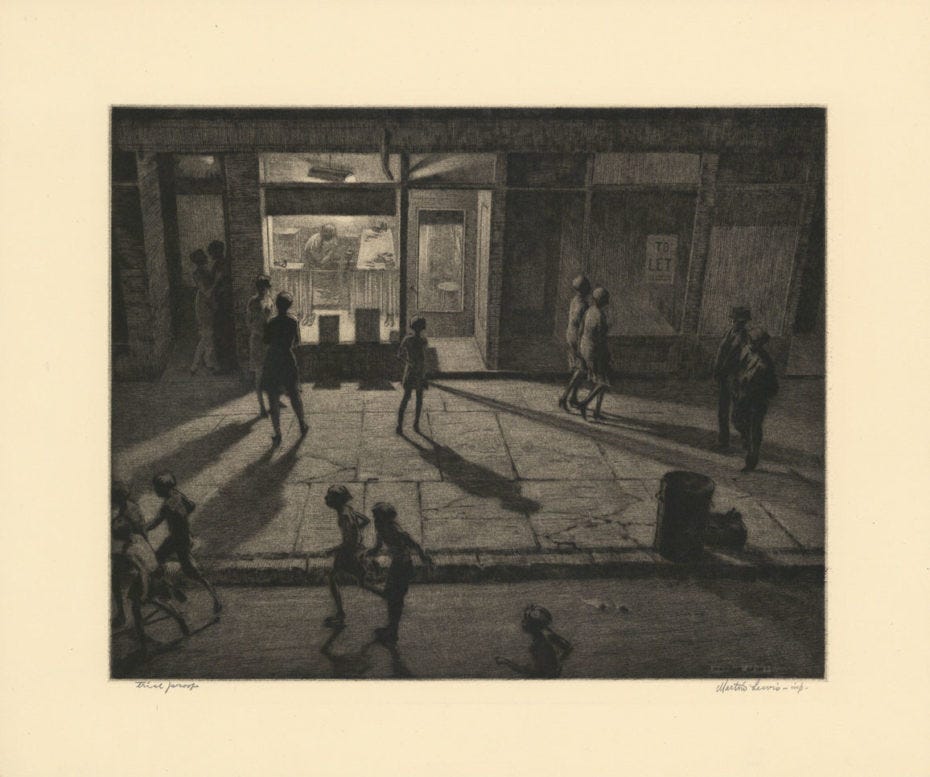

The artist: Martin Lewis died in obscurity in 1962; a retired art teacher who had found some success in his early career, but was largely forgotten after the Great Depression took away the demand for his craft, leaving Lewis to spend his last three decades teaching other people how to etch. History chose Edward Hopper for the fame game, but Martin Lewis was his mentor.