Alfred W. McCoy: What I Learnt From Fifty Years of Writing About Drugs

We live in a time of change, when people are questioning old assumptions and seeking new directions. In the ongoing debate over health care, social justice, and border security, there is, however, one overlooked issue that should be at the top of everyone’s agenda, from Democratic Socialists to libertarian Republicans: America’s longest war. No, not the one in Afghanistan. I mean the drug war.

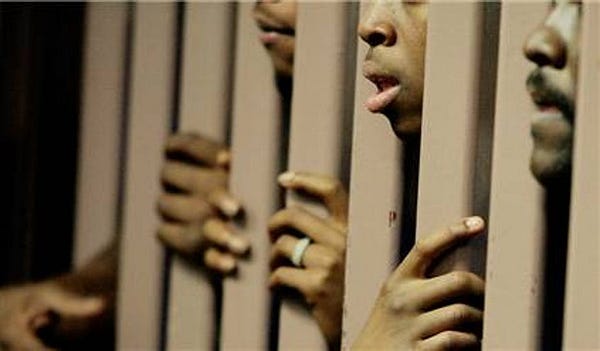

For more than a century, the U.S. has worked through the U.N. (and its predecessor, the League of Nations) to build a harsh global drug prohibition regime — grounded in draconian laws, enforced by pervasive policing, and punished with mass incarceration.

For the past half-century, the U.S. has also waged its own “war on drugs” that has complicated its foreign policy, compromised its electoral democracy, and contributed to social inequality. Perhaps the time has finally come to assess the damage that drug war has caused and consider alternatives.

Even though I first made my mark with a 1972 book that the CIA tried to suppress on the heroin trade in Southeast Asia, it’s taken me most of my life to grasp all the complex ways this country’s drug war, from Afghanistan to Colombia, the Mexican border to inner-city Chicago, has shaped

American society.

Last summer, a French director doing a documentary interviewed me for seven hours about the history of illicit narcotics. As we moved from the seventeenth century to the present and from Asia to America, I found myself trying to answer the same relentless question: What had 50 years of observation actually drilled into me, beyond some random facts, about the character of the illicit traffic in drugs?

At the broadest level, the past half-century turns out to have taught me that drugs aren’t just drugs, drug dealers aren’t just “pushers,” and drug users aren’t just “junkies” (that is, outcasts of no consequence).

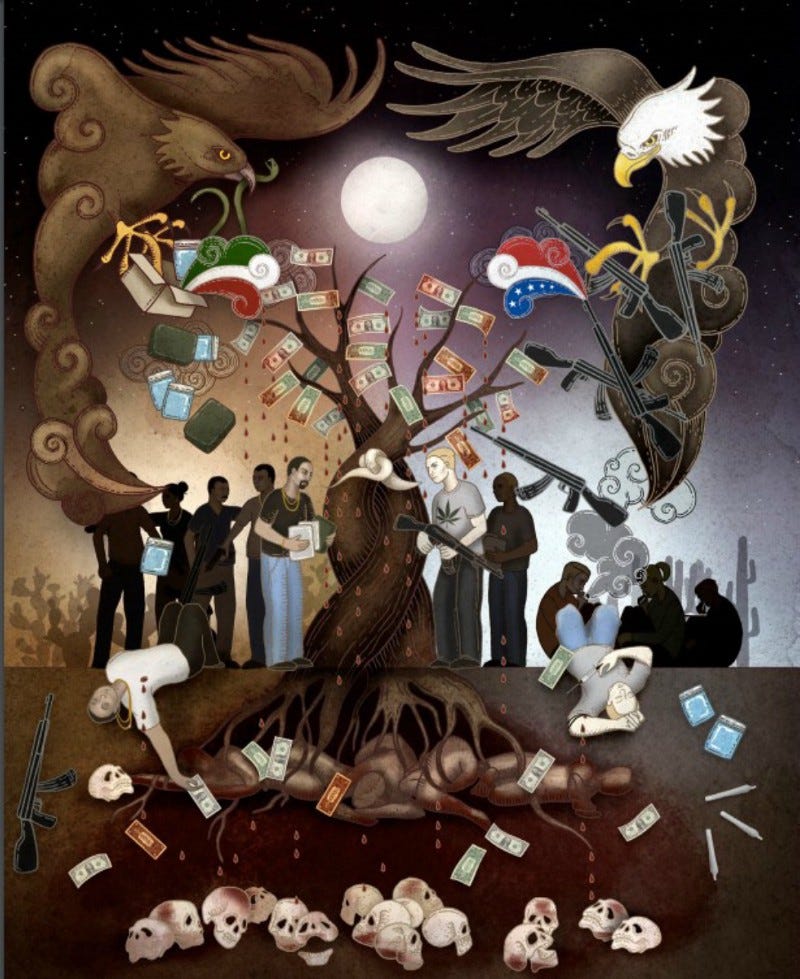

Illicit drugs are major global commodities that continue to influence U.S.

politics, both national and international. And our drug wars create profitable covert netherworlds in which those very drugs flourish and become even more profitable. Indeed, the U.N. once estimated that the transnational traffic, which supplied drugs to 4.2% of the world’s adult population, was a $400 billion industry, the equivalent of 8% of global trade.

Decriminalizing the Drug War

In ways that few seem to understand, illicit drugs have had a profound influence on modern America, shaping our international politics, national elections, and domestic social relations. Yet a feeling that illicit drugs belong to a marginalized demimonde has made U.S. drug policy the sole property of law enforcement and not health care, education, or urban development.

During this process of reflection, I’ve returned to three conversations I had back in 1971 when I was a 26-year-old graduate student researching that first book of mine, The Politics of Heroin:

CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade.

In the course of an 18-month odyssey around the globe, I met three men, deeply involved in the drug wars, whose words I was then too young to

fully absorb.

The first was Lucien Conein, a “legendary” CIA operative whose covert career ranged from

parachuting into North Vietnam in 1945 to train communist guerrillas with Ho Chi Minh to

organizing the CIA coup that killed South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem in 1963.

In the course of our interview at his modest home near CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, he laid out just how the Agency’s operatives, like so many Corsican gangsters, practiced the “clandestine arts” of conducting complex operations beyond the bounds of civil society and how such “arts” were, in fact, the heart and soul of both covert operations and the drug trade.

Second came Colonel Roger Trinquier, whose life in a French drug netherworld extended from commanding paratroopers in the opium-growing highlands of Vietnam during the First Indochina War of the early 1950s to serving as deputy to General Jacques Massu in his campaign of murder and torture in the Battle of Algiers in 1957.

During an interview in his elegant Paris apartment, Trinquier explained how he helped fund his own paratroop operations through Indochina’s illicit opium traffic. Emerging from that interview, I felt almost overwhelmed by the

aura of Nietzschean omnipotence that Trinquier had clearly gained from his many years in this shadowy realm of drugs and death.

My last mentor on the subject of drugs was Tom Tripodi, a covert operative who had trained Cuban exiles in Florida for the CIA’s 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion and then, in the late 1970s, penetrated mafia networks in Sicily for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

In 1971, he appeared at my front door in New Haven, Connecticut, identified himself as a senior agent for the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Narcotics, and insisted that the Bureau was worried about my

future book.

Rather tentatively, I showed him just a few draft pages of my manuscript for The Politics of Heroin and he promptly offered to help me make it as accurate as possible.

During later visits, I would hand him chapters and he would sit in a rocking chair, shirt sleeves rolled up, revolver in his shoulder holster, scribbling corrections and telling remarkable stories about the drug trade — like the time his Bureau found that French intelligence was protecting the Corsican syndicates smuggling heroin into New York City.

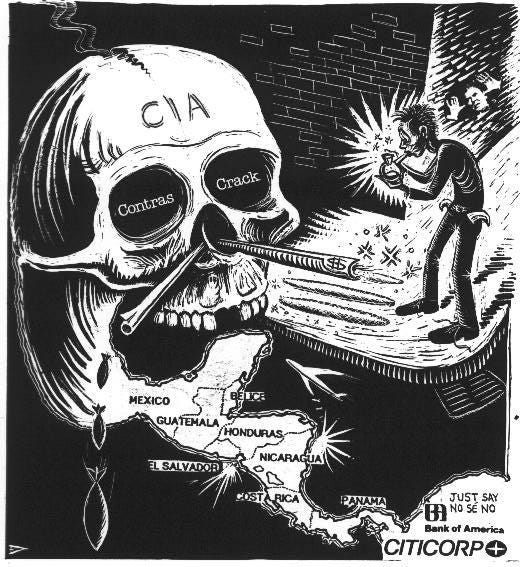

Far more important, though, through him I grasped how ad hoc alliances between criminal traffickers and the CIA regularly helped both the

Agency and the drug trade prosper.

Calculating the Damage from a Century of Drug Prohibition

Looking back, I can now see how those veteran operatives were each describing to me a clandestine political domain, a covert netherworld in which government agents, military men, and drug traders were freed from the shackles of civil society and empowered to form secret armies,

overthrow governments, and even, perhaps, kill a foreign president.

At its core, this netherworld was then and remains today an invisible political realm inhabited by criminal actors and practitioners of Conein’s “clandestine arts.”

Offering some sense of the scale of this social milieu, in 1997 the United Nations reported that transnational crime syndicates had 3.3 million members worldwide who trafficked in drugs, arms, humans, and endangered species.

Meanwhile, during the Cold War, all the major powers — Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States — deployed expanded clandestine services worldwide, making covert operations a central facet of geopolitical power.

The end of the Cold War has in no way changed this reality.

For over a century now, states and empires have used their expanding powers for moral prohibition campaigns that have periodically transformed alcohol, gambling, tobacco, and, above all, drugs into an illicit commerce that generates sufficient cash to sustain covert netherworlds.

Drugs and U.S. Foreign Policy

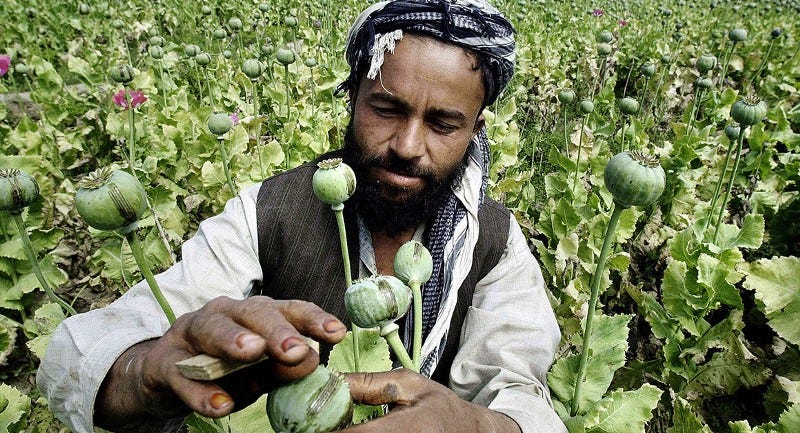

The influence of illicit drugs on U.S. foreign policy was evident between 1979 and 2019 in the abysmal failure of its never-ending wars in Afghanistan.

Over a period of 40 years, two U.S. interventions there fostered all the conditions for just such a covert netherworld. While mobilizing

Islamic fundamentalists to fight the Soviet occupation of that country in the 1980s, the CIA tolerated opium trafficking by its Afghan mujahedeen allies, while arming them for a guerrilla war that would ravage the countryside, destroying conventional agriculture and herding.

In the decade after superpower intervention ended in 1989, a devastating civil war and then Taliban rule only increased the country’s dependence upon drugs, raising opium production from 250 tons in 1979 to 4,600 tons by 1999.

This 20-fold increase transformed Afghanistan from a diverse agricultural economy into a country with the world’s first opium monocrop — that is, a land thoroughly dependent on illicit drugs for exports, employment, and taxes.

Demonstrating that dependence, in 2000 when the Taliban banned opium in a bid for diplomatic recognition and cut production to just 185 tons, the rural economy imploded and their regime collapsed as the first U.S. bombs fell in October 2001.

To say the least, the U.S. invasion and occupation of 2001–2002 failed to effectively deal with the drug situation in the country. As a start, to capture the Taliban-controlled capital, Kabul, the CIA had mobilized Northern Alliance leaders who had long dominated the drug trade in northeast

Afghanistan, as well as Pashtun warlords active as drug smugglers in the southeastern part of the country.

In the process, they created a post-war politics ideal for the expansion of opium cultivation.

Even though output surged in the first three years of the U.S. occupation, Washington remained uninterested, resisting anything that might weaken military operations against the Taliban guerrillas.

Testifying to this policy’s failure, the U.N.’s Afghanistan Opium Survey 2007 reported that the harvest that year reached a record 8,200 tons, generating 53% of the country’s gross domestic product, while accounting for 93% of the world’s illicit narcotics supply.

When a single commodity represents over half of a nation’s economy,

everyone — officials, rebels, merchants, and traffickers — is directly or

indirectly implicated.

In 2016, The New York Times reported that both Taliban rebels and provincial officials opposing them were locked in a struggle for control of the lucrative drug traffic in Helmand Province, the source of nearly half the country’s opium.

A year later, the harvest reached a record 9,000 tons, which, according to the U.S. command, provided 60% of the Taliban’s funding. Desperate to cut that funding, American commanders dispatched F-22 fighters and B-52 bombers to destroy the insurgency’s heroin laboratories in Helmand — doing

inconsequential damage to a handful of crude labs and revealing the

impotence of even the most powerful weaponry against the social power

of the covert drug netherworld.

With unchecked opium production sustaining Taliban resistance for the

past 17 years and capable of doing so for another 17, the only U.S. exit strategy now seems to be restoring those rebels to power in a coalition government — a policy tantamount to conceding defeat in its longest military intervention and least successful drug war.

High Priests of Prohibition

For the past half-century, the ever-failing U.S. drug war has found a compliant handmaiden at the U.N., whose dubious role when it comes to drug policy stands in stark contrast to its positive work on issues like climate change and peace-keeping.

In 1997, the director of U.N. drug control, Dr. Pino Arlacchi, proclaimed a 10-year program to eradicate all illicit opium and coca cultivation from the face of the planet, starting in Afghanistan.

A decade later, his successor, Antonio Maria Costa, glossing over that failure, announced in the U.N.’s World Drug Report 2007 that “drug control is working and the world drug problem is being

contained.”

While U.N. leaders were making such grandiloquent promises about drug prohibition, the world’s illicit opium production was, in fact, rising 10-fold from just 1,200 tons in 1971, the year the U.S. drug war officially started, to a record 10,500 tons by 2017.

This gap between triumphal rhetoric and dismal reality cries out for an explanation.

That 10-fold increase in illicit opium supply is the result of a market dynamic I’ve termed:

The stimulus of prohibition.

At the most basic level, prohibition is the necessary precondition for the global narcotics trade, creating both local drug lords and transnational syndicates that control this vast commerce.

Prohibition, of course, guarantees the existence and well-being of such criminal syndicates which, to evade interdiction, constantly shift and build up their smuggling routes, hierarchies, and mechanisms, encouraging a worldwide proliferation of trafficking and consumption, while ensuring that the drug netherworld will only grow.

In seeking to prohibit addictive drugs, U.S. and U.N. drug warriors act as if mobilizing for forceful repression could actually reduce drug trafficking, thanks to the imagined inelasticity of, or limits on, the global narcotics supply.

In practice, however, when suppression reduces the opium supply from one area (Burma or Thailand), the global price just rises, spurring traders and

growers to sell off stocks, old growers to plant more, and new areas (Colombia) to enter production.

In addition, such repression usually only increases consumption. If drug seizures, for instance, raise the street price, then addicted consumers will maintain their habit by cutting other expenses (food, rent) or raising their income by dealing drugs to new users and so expanding the trade.

Instead of reducing the traffic, the drug war has actually helped stimulate that 10-fold increase in global opium production and a parallel surge in U.S. heroin users from just 68,000 in 1970 to 886,000 in 2017.

By attacking supply and failing to treat demand, the U.N.-U.S. drug war has been pursuing a “solution” to drugs that defies the immutable law of supply and demand.

As a result, Washington’s drug war has, in the past 50 years, gone from defeat to debacle.

The Domestic Influence of Illicit Drugs

That drug war has, however, incredible staying power. It has persisted despite decades of failure because of an underlying partisan logic.

In 1973, while President Richard Nixon was still fighting his drug war in Turkey and Thailand, New York’s Republican governor, Nelson Rockefeller,

enacted the notorious “Rockefeller Drug Laws.” Those included mandatory penalties of 15 years to life for the possession of just four ounces of narcotics.

As the police swept inner-city streets for low-level offenders, annual prison sentences in New York State for drug crimes surged from only 470 in 1970 to a peak of 8,500 in 1999, with African- Americans representing 90% of those incarcerated. By then, New York’s state prisons held a previously unimaginable 73,000 people.

During the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan, a conservative Republican, dusted off Rockefeller’s anti-drug campaign for intensified domestic

enforcement, calling for a “national crusade” against drugs and winning draconian federal penalties for personal drug use and small-scale dealing.

For the previous 50 years, the U.S. prison population had remained remarkably stable at just 110 prisoners per 100,000 people. The new drug war, however, doubled those prisoners from 370,000 in 1981 to 713,000 in 1989.

Driven by Reagan-era drug laws and parallel state legislation, prison inmates soared to 2.3 million by 2008, raising the country’s incarceration rate to an extraordinary 751 prisoners per 100,000 population. And 51% of those in federal penitentiaries were there for drug offenses.

Such mass incarceration has led as well to significant disenfranchisement, starting a trend that would, by 2012, deny the vote to nearly six million people, including 8% of all African-American voting-age adults, a liberal constituency that had gone overwhelmingly Democratic for more than

half a century.

America’s Self-Inflicted Wound

In addition, this carceral regime concentrated its prison populations, including guards and other prison workers, in conservative rural districts of the country, creating something akin to latter-day “rotten boroughs” for the Republican Party.

Take, for example, New York’s 21st Congressional District, which covers the Adirondacks and the state’s heavily forested northern panhandle. It’s home to 14 state prisons, including some 16,000 inmates, 5,000 employees, and their 8,000 family members — making them collectively the district’s largest employer and a defining political presence.

Add in the 13,000 or so troops in nearby Fort Drum and you have a reliably conservative bloc of 26,000 voters (and 16,000 non-voters), or the largest political force in a district where only 240,000 residents actually vote.

Not surprisingly, the incumbent Republican congresswoman survived the 2018 blue wave to win handily with 56% of the vote. (So never say that the drug war had no effect.)

So successful were Reagan Republicans in framing this partisan drug policy as a moral imperative that two of his liberal Democratic successors, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, avoided any serious reform of it. Instead of systemic change, Obama offered clemency to about 1,700 convicts, an insignificant handful among the hundreds of thousands still locked up for non-violent

drug offenses.

While partisan paralysis at the federal level has blocked change, the separate states, forced to bear the rising costs of incarceration, have slowly begun reducing prison populations. In a November 2018 ballot measure, for instance, Florida — where the 2000 presidential election was

decided by just 537 ballots — voted to restore electoral rights to the state’s 1.4 million felons, including 400,000 African-Americans.

No sooner did that plebiscite pass, however, than Florida’s Republican legislators desperately tried to claw back that defeat by requiring that the same felons pay fines and court costs before returning to the electoral rolls.

Not only does the drug war influence U.S. politics in all sorts of negative ways but it has reshaped American society — and not for the better, either. The surprising role of illicit drug distribution in ordering life inside some of the country’s major cities has been illuminated in a careful study by a University of Chicago researcher who gained access to the financial records of

a drug gang inside Chicago’s impoverished Southside housing projects.

He found that, in 2005, the Black Gangster Disciple Nation, known as GD, had about 120 bosses who employed 5,300 young men, largely as street dealers, and had another 20,000 members aspiring to those very jobs.

While the boss of each of the gang’s hundred crews earned about $100,000 annually, his three officers made just $7.00 an hour, his 50 street dealers only $3.30 an hour, and their hundreds of other members served as unpaid apprentices, vying for entry-level slots when street dealers were killed, a fate which one in four regularly suffered.

So what does all this mean?

In an impoverished inner city with very limited job opportunities, this

drug gang provided high-mortality employment on a par with the minimum wage (then $5.15 a hour) that their peers in more affluent neighborhoods earned from much safer work at McDonald’s.

Moreover, with some 25,000 members in Southside Chicago, GD was providing social order for young men in the volatile 16-to-30 age cohort — minimizing random violence, reducing petty crime, and helping Chicago maintain its gloss as a world-class business center.

Until there is sufficient education and employment in the nation’s cities, the illicit drug market will continue to fill the void with work that carries a high cost in violence, addiction, imprisonment, and more generally blighted lives.

The End of Drug Prohibition

As the global prohibition effort enters its second century, we are witnessing two countervailing trends.

The very idea of a prohibition regime has reached a crescendo of dead-end violence not just in Afghanistan but recently in Southeast Asia, demonstrating the failure of the drug war’s repression strategy.

In 2003, Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra launched a campaign

against methamphetamine abuse that prompted his police to carry out 2,275 extrajudicial killings in just three months.

Carrying that coercive logic to its ultimate conclusion, on his first day as

Philippine president in 2016, Rodrigo Duterte ordered an attack on drug trafficking that has since yielded 1.3 million surrenders by dealers and users, 86,000 arrests, and some 20,000 bodies dumped on city streets across the country.

Yet drug use remains deeply rooted in the slums of both Bangkok and Manila.

On the other side of history’s ledger, the harm-reduction movement led by medical practitioners and community activists worldwide is slowly working to unravel the global prohibition regime.

With a 1996 ballot measure, California voters, for instance, started a trend by legalizing medical marijuana sales. By 2018, Oklahoma had become the 30th state to legalize medical cannabis.

Following initiatives by Colorado and Washington in 2012, eight more states to date have decriminalized the recreational use of cannabis, long the most widespread of all illicit drugs.

Hit by a surge of heroin abuse during the 1980s, Portugal’s government first reacted with repression that, as everywhere else on the planet, did little to stanch rising drug abuse, crime, and infection.

Gradually, a network of medical professionals across the country adopted harm- reduction measures that would provide a striking record of proven success.

After two decades of this ad hoc trial, in 2001 Portugal decriminalized the possession of all illegal drugs, replacing incarceration with counseling and producing a sustained drop in HIV and hepatitis infections.

Projecting this experience into the future, it seems likely that harm-reduction measures will be adopted progressively at local and national levels around the globe, while various endless and unsuccessful wars on drugs are curtailed or abandoned.

Perhaps someday a caucus of Republican legislators in some oak-paneled Washington conference room and a choir of U.N. bureaucrats in their glass-towered Vienna headquarters will remain the only apostles preaching the discredited gospel of drug prohibition.

Alfred W. McCoy is the Harrington professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade, the now-classic book which probed the conjuncture of illicit narcotics and covert operations over 50 years, and most recently In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power (Dispatch Books).

This story was originally published on the Tom Despatch news site.

It is reproduced here with the kind permission of the author.