A Year of Living With Discredited Mathematical Models: Best of the Archives.

By Professor Ramesh Thakur and David Redman

After a year’s experience of COVID-19 worldwide, the continuing hold of discredited mathematical models regarding lockdowns remain. As well, it is increasingly evident that medical specialists put in charge of public policy ignored existing pandemic preparedness plans, for better or worse.

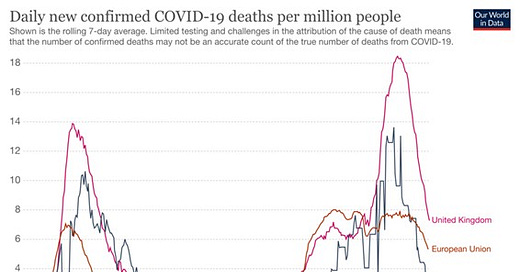

On 18 February, SKY News UK trumpeted: “Lockdown is working! COVID-19 infection rate plummets in England.” Yet, as Figure 1 shows, voluntary social distancing in Sweden resulted in an earlier and faster decline of COVID-19 deaths per capita. Another interesting feature of the chart is how the curves are policy-invariant, mimicking one another regardless of policy interventions between the various countries. The virus infection, hospitalisation, and mortality curves seem to rise and fall by seasons independently of lockdowns.

Figure 1: The UK, EU, and Sweden

Source: Our World in Data.

A year ago, Western countries began adopting lockdown policies. To mark the anniversary, we would like to raise four analytical puzzles. The first is why abstract models have proven so seductive. On 13 February, the sober and responsible Economist magazine said “the pandemic threatened to take more than 150 million lives.” It gave no source or explanation for this Spanish Flu-like estimate. Neil Ferguson of Imperial College London (ICL) has a notorious track record of catastrophic predictions out by orders of magnitude on foot and mouth disease, mad cow disease, bird flu, and swine flu.

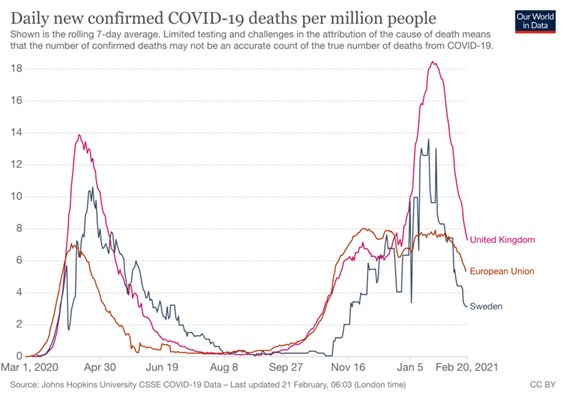

The ICL model of 16 March 2020 on COVID-19 and others copying its methodology too proved wildly inaccurate on both worst and best case estimates of COVID-19 deaths with respect to the UK, US, Sweden, and even Australia. As well, on 19 February, Canadian health officials couldn’t explain to a parliamentary health committee the basis for modelling-based forecasts from chief health officer Dr Theresa Tam that showed a rocket lift-off-like vertical trajectory (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Canada’s Rocket Model

Source: Toronto Sun, 20 February 2021.

The second is why countries have persisted with a policy whose many harms are far easier to demonstrate than benefits. If lockdowns worked, Sweden would have a higher death rate than the worst-hit European countries, and Florida would be far worse off than locked-down California, New York, and many more states. Data indicates the opposite.

On 11 February, Governor Ron DeSantis pointed out that since December, Florida ranked 28th among US states on cases, 38th on hospitalisations, and 42nd on deaths per capita. In an MSNBC interview on 17 February, President Joe Biden’s COVID-19 adviser Andy Slavitt visibly struggled to explain comparable outcomes for lockdown California and no-lockdown Florida, stating “that’s just a little beyond our explanation.”

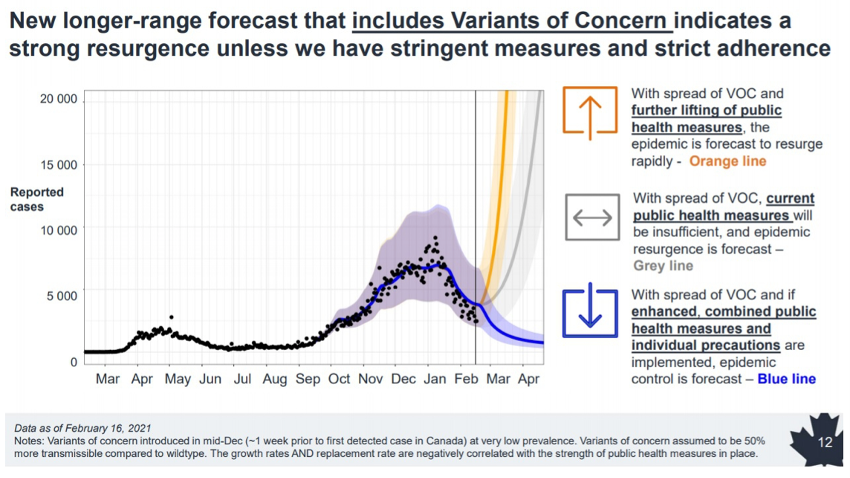

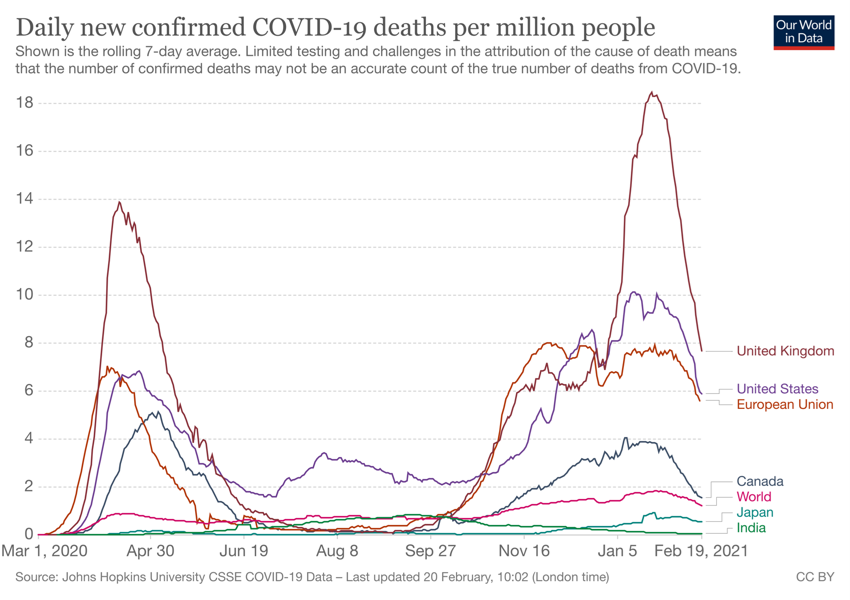

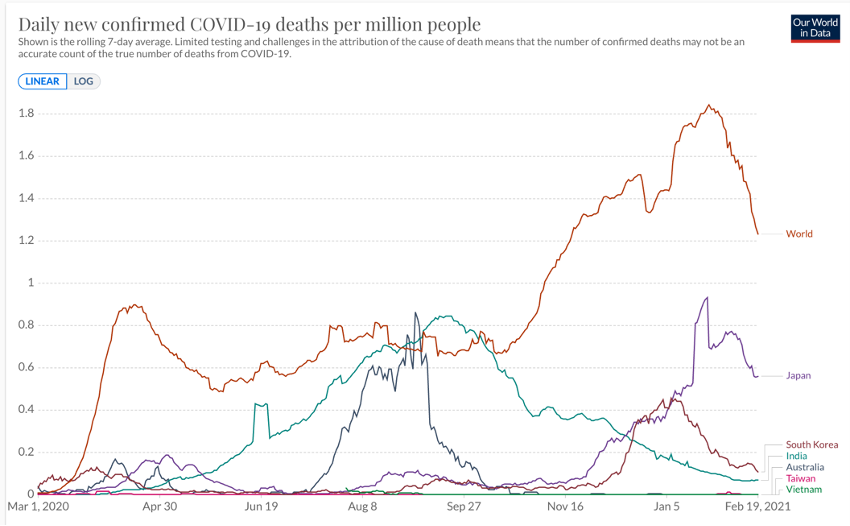

Governments are prone to use the worst-performing countries as benchmarks to pat their own backs. Thus, Canada’s 570 COVID-19 deaths per million (DPM) compares very favourably to the 1,535 DPM in the US, but Canada is 80 percent above the world average of 317 DPM, and significantly worse than many Asian countries (Figure 3). Australia’s 35 DPM is spectacular in comparison to the tolls in Europe and the Americas, but in the mid-range of the Asia-Pacific statistics (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Canada in Global Perspective

Figure 4: Australia in Global and Regional Perspective

Despite a rudimentary public health infrastructure, multigenerational shared accommodation in congested conditions, and a vast migrant labour population returning from India, Nepal’s infection and mortality rates fell sharply, to the puzzlement of public health experts.

India’s low COVID-19 mortality rate and falling infections are a similar puzzle. In December, Politico ran a headline demonstrating similar confusion, writing “Locked-down California runs out of reasons for surprising surge.”

Experts are similarly baffled by the failure of any post-holiday surge in Iowa despite dire predictions.

Against barely discernible benefits, the immediate and lasting harms of lockdowns to health, mental health, livelihoods, and social life are immense.

DAVID REDMAN AND RAMESH THAKUR

A peer-reviewed article in the European Journal of Clinical Investigation by researchers from Stanford University showed that net harms exceed net gains between highly and less restrictive interventions. In the UK, 3 million people missed cancer screenings and heart attacks, Accident and Emergency attendance dropped by 50 percent, and almost half of the 220,000 deaths were from non-COVID-19 causes, such as cancelled operations.

In Canada too, lockdowns have caused massive mental health, societal health, educational, economic, and even public health damage, including deaths from other severe diseases because people are either turned away from hospitals focussed on COVID-19, or are too frightened to go to the hospital.

Australia’s former foreign minister, Alexander Downer, described elimination as a “strategy that will never work,” articulating that its pursuit would be “the greatest danger for Australia” that will “cause the collapse of the economy, massive social dislocation, depression, educational setbacks, and the collapse of small businesses.”

No government should ever again have the power to shut down our lives, businesses, culture, and liberties.

Third, one explanation for the failure to control the pandemic could be that doctors have been delegated authority to make policy decisions that should have been tasked instead to emergency management experts, with input from public health specialists within their domain of expertise.

A pandemic is not a public health emergency, it’s a public emergency. It affects every aspect of life: the public sector, private sector, every citizen.

Every Canadian province has an Emergency Management Organization that scans across all sectors of the economy daily, looking for hazards that are going to impact them, making sure critical infrastructure is operating, and giving governments the tools needed to ensure the stability of their jurisdiction.

They have been pushed aside by chief health officers who are not trained in any of this. As non-medics would be barred from hospital operating theatres, why then do we expect good outcomes from health professionals with no expertise and experience in emergency management planning and execution of operational plans?

Fourth, Sweden’s chief epidemiologist Anders Tegnell was correct in his observation last April that lockdowns have no “historical scientific basis.”

The scepticism towards harsh mitigation measures was stated by the WHO in 2006, 2019, and again last December. National pandemic preparedness plans reflected the prevailing scientific and policy consensus. East Asian countries have had significantly lower COVID-19 death tolls and collateral damage to livelihoods and lifestyles because their pandemic plans were swiftly activated against COVID-19. By contrast, having reaffirmed in February 2020 its existing pandemic preparedness plan that had been drawn up in 2011, the UK abandoned any plan in March. Canada too had well-defined plans based on the hard lessons learned from previous pandemics. These were all discarded.

Going forward, the key question is what the acceptable level of mortality risk, relative to the damage to health, mental health, society, economy, and disadvantaged groups like migrants and the poor from lockdowns is.

Instead of fear-driven hysteria, governments should emphasise balance and proportionality and project calm, competence, and composure.

COVID-19 is now endemic and will keep circulating, returning (especially in winters), and mutating.

We cannot endlessly repeat lockdown cycles. The overall goal should be risk management, not risk avoidance, denial, or eradication. We must break the cycle of fear with a clear plan that people can understand and support.

This story was originally published by the Australian Institute of International Affairs and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence.

David Redman is a retired Canadian Army Lt. Col and a former head of Emergency Management Alberta.

Ramesh Thakur is a former UN Assistant Secretary-General and a Canadian as well as Australian citizen, is emeritus professor in the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University.

Stories by Professor Thakur published in A Sense of Place Magazine can be found here.